Since former Mexican President Felipe Calderon’s declaration of War on Drugs in 2006, 18,000 deaths have occurred due to drug war related violence. Among the thousands dead was the son of Javier Sicilia, a Mexican poet and activist.

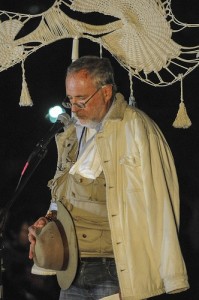

On Oct. 30, Sicilia spoke at Encina Hall about his involvement in the Movement for Peace and Justice with Dignity (MPJD), a program aimed at stopping drug trafficking. During his lecture, Sicilia spoke about the toll such criminal activity took not only on his country but also his family: His son and his friends were assassinated while trying to retrieve a friend’s phone left behind at a night club.

“They were killed together, and that’s when I decided to dedicate myself to this activism,” Sicilia said. “I’m from a Catholic family with a deep sense of social justice and empathy, within that vision.”

Sicilia, who began writing poetry at a very early age, always felt that poets and poetry are deeply connected to social issues and that it is important for the two to be combined. In fact, he considers René Char, French poet and leader of the French Resistance, and Albert Camus to be two of his literary heroes due to their involvement in politics.

“To me those two are people that connect with me and make me feel that I must write poetry, I must also be political,” he said.

However, following his son’s death in 2011, Sicilia stopped writing poetry because he felt as though he could no longer utilize the art form to convey his grief.

“You never stop writing in your head; I’m just not sharing poetry,” Sicilia said. “The words don’t reach far enough to express the suffering.”

Instead of writing poetry, Sicilia writes essays and novels and works as a journalist, focusing on political analysis. He refers to these as his “natural spaces.”

Now, Sicilia devotes the majority of his time to his activism.

“The drugs are moving up here to the United States and the guns that are killing the Mexicans come from the United States. So we’ve come back to talk about these issues, to follow up,” Sicilia said.

According to Sicilia, Mexico has seen 18,000 deaths due to drugs per year since 2007. “This is not just a Mexican problem. The U.S. does not know how to look at its neighbor,” Sicilia said. “It does not know how to see that many of its internal policies affect in a brutal way the lives of citizens in other countries.”

In the past seven years, Sicilia has tried to work with different U.S. and Mexican legislators to pass laws that might affect drug trafficking, but to little avail.

“Governments are very slow and torpid,” he said. “And they are very slow to understand things and change policies, but we continue to pressure.”

Using this tenacity, Sicilia and others led a caravan from Cuernavaca to Mexico City. The journey lasted four days and gathered thousands of people in plazas throughout Mexico.

“Finally, the government of Calderon said we want to speak with you,” Sicilia said. “We said that they had to be public dialogues. We don’t only want the visibility and pain of the victims but something that is good.”

As a result of successful protests like the caravan from Cuernavaca to Mexico City, Mexican President Peña Nieto signed The Victims Law on Jan. 9, 2013. According to Sicilia, the new piece of legislation aims to provide reparations for the victims of drug trafficking crime.

“Victims had been abandoned and we had to return their dignity,” he said. “This was harsh for the state but good for victims. This shows the weaknesses of the state by accusing the state of violating human and civil rights of human citizenry.”

Even with this new policy, the war continues and the country has become balkanized, Sicilia said, now that there is a flow of 100s to 1000s of weapons through the US-Mexico border.

“Weapons can be purchased easily, and they are going to my country,” he said. “When you try to control drug trafficking and fight the army and leaders of cartels, the groups of criminals and assassins who are organized by drug leaders start to do human trafficking, kidnappings when they cannot have access to drugs.”

Looking forward, Sicilia wants the United States to take responsibility for its actions in the past.

“The U.S. needs to consider drugs as a matter of public health and liberties, not of national security,” he said. “The same policies for drugs should be the same as those for anti-smoking and anti-tobacco.”

Although Sicilia does not consider himself an idealist, he notes with humility that he and his group will do all it can to put a stop to this war.

“Do you know the Sisyphus myth? People are carrying the rock up; I know I’m not going to reach the top, but it’s important that I keep trying to get there,” he said. “You do it because it’s good, because it’s beautiful, even if we don’t get there.”