At the end of the Rose Bowl, it seemed like either team could have won or lost by two touchdowns. That’s a good game in anyone’s book. Stanford lost to Michigan State in the 100th Rose Bowl, but while losing is never fun to watch, the Cardinal and the Spartans definitely played an instant classic in Pasadena.

Everyone expected Michigan State’s defense to come out and play, and it did. The Spartan D was helped immensely by its special teams, which neutralized Stanford’s top-ranked returners —Stanford’s offense was routinely stuck deep in its own territory — and it took spectacular showings by kicker Jordan Williamson (touchbacks on all five kickoffs) and punter Ben Rhyne (49.8 yards per punt) to keep Stanford in the game.

What was especially surprising, however, was that Stanford gave up 24 points to the Spartan offense.

Michigan State’s offense has been a bit of a national punch line in recent years. By season’s end, however, the Rose Bowl proved confident MSU fans correct: Michigan State’s offense, once sputtering, was a solid unit. Vegas favored Stanford by a touchdown; that was probably a mistake. The Spartans outplayed Stanford in all three phases of the game and, as much as it hurts to admit it, they deserved to win.

Stanford’s defense still kept the Cardinal in the game, however. Although Spartan quarterback Connor Cook was excellent when given time, he was shaky under pressure and made a number of horrendous decisions. And when Stanford’s offense sputtered, defensive coordinator Derek Mason’s unit put up some points on its own — linebacker Kevin Anderson returned an interception for a touchdown late in the second quarter.

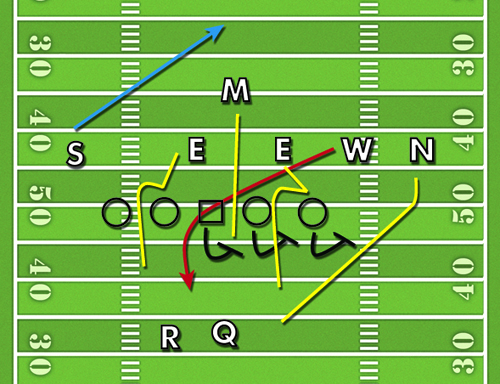

With just over two minutes left in the first half, Michigan State was only at its own 45-yard line. The Spartans were facing second-and-6 and pressing, and Mason decided to try to bait Cook into a mistake. He called a 3-3 zone blitz, fielding three deep defenders and another three under them. Although the play call was vulnerable on short routes, it was both solid against the deep ball and able to blitz five men instead of the usual four.

The purpose of the zone blitz is to mix confusing coverages with blitz pressure, and it worked to perfection against the Spartans. Aware of its own tendencies, the Cardinal showed an unexpected look on this play. Fifth-year senior nickelback Usua Amanam (N) — lined up in coverage before the snap — set up shop on the line of scrimmage after Cook had called the play, and it was too late for Cook to change the pass protection. With six defensive players against five offensive linemen, MSU couldn’t run the ball. Meanwhile, safety Jordan Richards (not pictured for clarity), normally the last line of the defense, headed to the flat, filling Amanam’s role.

Perhaps most surprisingly, linebacker Trent Murphy (S) — the nation’s premier sack master — dropped back into coverage (blue line) to rob short crossing routes. As a pass rusher, Murphy is so dominant that no offensive coordinator should consider blocking him with a running back. As such, it was unthinkable for MSU to execute a traditional full slide protection to the right, where the running back blocks Murphy and all the linemen block right. Meanwhile, there was no way to slide left because Stanford outnumbered the defense on the right so greatly. But schematically, slide protection is the soundest option an offensive line can take. By having linemen block areas instead of specific men, the protection can hold against blitzers who loop from one gap to another.

Michigan State decided to go half-slide: man-on-man to the left with two blockers and a slide to the right with three, a mirror image of what Stanford did on the critical play against USC. With fifth-year senior inside linebacker Shayne Skov walking up to the line of scrimmage, MSU’s center anticipated a blitz and decided to help to the right (toward Skov) instead of to the left. As with USC against the Cardinal, the defense’s best shot was to attack where the man-blocking ended and the slide protection began.

The blitz was already very favorable because of the geometry of the play: There was nobody nearby to block Amanam. MSU’s right tackle was too far away to block him properly, and while the Spartan running back was in the backfield to block free blitzers, most half-slides put the back on the man side of the formation — the wrong side in that case. With the running back placed behind the quarterback, Amanam was free to take target practice at Cook.

With Amanam pressuring on the right, linebacker Kevin Anderson (W) could devote his energies to attacking the left. The blitz was essentially designed for him: On the left, sophomore defensive end Aziz Shittu (E) engaged his man (MSU’s left guard) and forced him left, while Skov (M) occupied the center, already sliding right. Anderson looped around Skov (red line) and senior defensive end Henry Anderson (E on the right), intending to drive through the gap, where he would have a favorable matchup against a running back. Looping is in general a counterintuitive idea, which is why it was effective here: It changed the internal mathematics of the play, putting a man where MSU didn’t expect there to be one. This was not a very run-sound tactic, but against a pass it could be useful.

By not giving MSU’s right side specific man assignments, the slide scheme allowed the Spartan right guard to head upfield and disrupt Anderson’s path to the gap. But Amanam had Cook on his heels immediately, and by delaying Anderson’s attack, MSU ironically put the linebacker in perfect position to catch Cook’s desperate heave. Already in the backfield, Anderson had no Spartans in front of him and ran straight to the end zone.

More than anything else, Anderson’s interception was what made the Rose Bowl such a brilliant back-and-forth affair. Even though MSU played better overall, Stanford had its chances to win, and similar defensive pressure created two more gilt-edged interception chances that bounced out of Stanford defenders’ hands. For all the hand wringing that occurred, the Cardinal had the ball at the end with a chance to win the game and failed. The Rose Bowl wasn’t a crushing defeat. But it hurt all the same.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.