Due to higher retention rates and higher yield in searches, the School of Humanities and Sciences has experienced a seven-percent increase in faculty in the last couple of years, bringing the total number of full-time faculty positions to 553—the highest in its history.

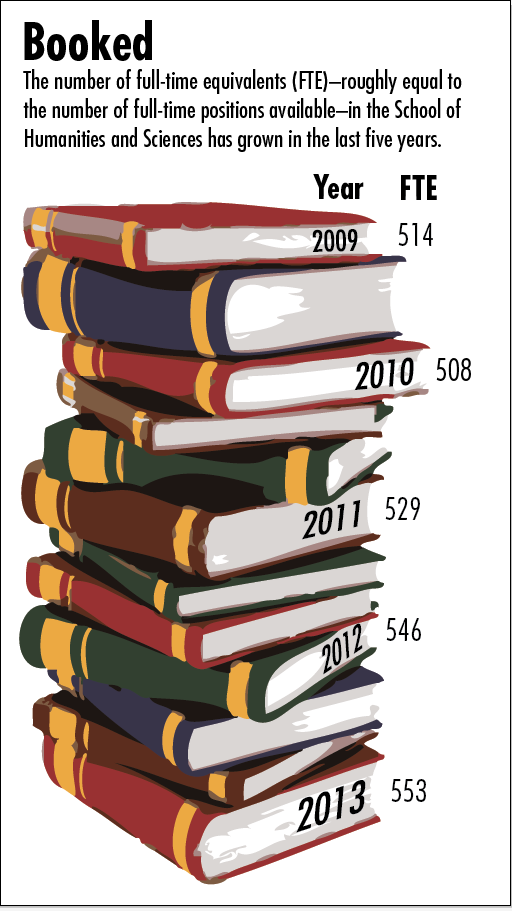

Despite a slight decline just after the recession, the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs), where a half-time faculty member would count as 0.5, has grown steadily over the past five years. According to Richard Saller, dean of the school of Humanities and Sciences, the number of FTEs in the school has grown from 514 in September 2009 to 553 in September 2013.

Saller attributed the increase to a variety of reasons, including the decline of departing tenured faculty and a higher yield of faculty searches.

Before 2010, an average of 13 tenured faculty members departed from the University each year for positions in other institutions, but in the past three years, fewer than three have departed each year. In addition to a much higher retention rate, the average percent yield of successful faculty searches has grown, from half to two-thirds of the searches.

“With fewer faculty leaving and more faculty accepting offers, the size of [the School of Humanities and Sciences] has gone up much more dramatically than anticipated,” Saller said.

The increasing retention rate and higher search yield of faculty are indicative of a higher incentive for faculty to be working at Stanford. These reasons range from the public school system in the area for faculty with families to the strong collaborations between departments within the University.

“I wanted very much to go back to academia and chose Stanford for a myriad of reasons,” said Steven Chu, professor of physics. Chu served as the 12th U.S. Secretary of Energy from January 2009 to April 2013 before returning to Stanford.

“I love the atmosphere at Stanford, the interactions I have here, the collaborations in various departments and many of my friends are here. [Returning to Stanford] was like a sort of homecoming,” Chu added.

The departments within the School of Humanities and Sciences rank high nationally as well, according to Saller. In the U.S. News rankings of graduate programs, 11 of the departments are ranked, six of them number one and none of them ranked below five. He also added that less aggressive faculty hiring from other peer universities such as Harvard and Yale—due to financial concerns—may also add to the increased hiring of faculty at Stanford.

“Once you’re at Stanford, in a sense, you’ve made it,” Saller said. “Faculty will get the best graduate and undergraduates, and faculty want to teach good students and have good research support.

“There’s a sense that the science and engineering at Stanford is the best, and this is the destination university,” Saller added. “So when [faculty] arrive, they’re at the best place they can hope to be.”

However, faculty members do depart Stanford, and Saller admitted that one of the biggest difficulties in retention is being able to accommodate a spouse or partner—the main reason for faculty who do leave.

“Housing is hard, too,” he added. “But we do a good job hosting programs to help faculty get housing in one of the most expensive housing areas.”

The growth of the School of Humanities and Sciences does not stand alone.

Jim Plummer, dean of the School of Engineering, stated that the size of the engineering faculty has been growing over the past few years as well, at roughly the same rate as the School of Humanities and Sciences.

“The growth has been targeted at areas like bioengineering, which is our newest department, and in growing several of our smaller departments to critical mass size,” wrote Plummer in an email to The Daily. Plummer added that the Computer Science Department recently has done quite a fair amount of faculty hiring as well, partly due to growing student demand.

To some administrators, the increasing number of faculty in the School of Humanities and Sciences is concerning, Saller said, because of the burdens on administrative infrastructure and space and facilities. However, Saller doesn’t see the high FTE numbers as particularly disadvantageous.

“There are people who claim that there is a drawback, but I don’t think so,” Saller said. “If you have the number-one ranked department, you want to retain it.”

Contact Catherine Zaw at czaw13 ‘at’ stanford.edu.