Just before winter break, a group of five professors released a letter to faculty outlining their concerns with the University’s new Student Title IX procedures for adjudicating allegations of sexual violence. The letter’s authors consisted of sociology professor Shelley Correll M.A. ’96 Ph.D. ’01, law professor Michele Dauber, history professor Estelle Freedman, literature professor David Palumbo-Liu and professor of medicine Marcia Stefanick Ph.D. ’82.

The letter is in response to the recent release of the new adjudicative process, called the Student Title IX/Disciplinary process or “Draft Process,” which replaces the Alternate Review Process (ARP). The new policies are the result of last year’s report by the Provost’s Task Force on Sexual Assault, which provided direct recommendations for reforming the current system. The new policy was scheduled to go into effect on Jan. 4.

“This new policy would make Stanford one of the worst in the nation, and this was correctly highlighted by the faculty letter,” wrote Tessa Ormenyi ’14, who served as a student panelist on ARP cases from 2011 to 2013, in an email to The Daily.

Two of the professors who issued the letter served on the Task Force, and three teach about sexual assault at Stanford.

“We appreciate the Task Force’s deliberations and the thoughtful efforts made to improve university policies,” the letter reads. “At the same time, we have serious reservations about some of the proposed changes.”

The professors composed their recommendations after discussions with law school dean Liz Magill and hearing responses from students through the ASSU Sexual Assault Prevention Committee.

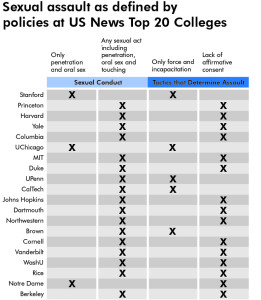

The letter was accompanied by a table comparing Stanford’s definitions of sexual offenses to those of peer schools, including members of the Ivy League, U.S. News & World Report’s Top 20 Colleges and the Pac-12 Conference. Stanford’s definitions are ranked as the narrowest or among the most narrow in every table.

Another table compares Stanford’s procedures for the adjudicative process to the same set of schools. To determine responsibility, Stanford requires a unanimous vote among the adjudication panel. None of the Ivy League schools require unanimity and only one other school in each of the U.S. News and Pac-12 lists require it.

Recommendations

The letter outlines four specific recommendations to revise the new process.

“Recommendation 1: We urge the use of panels comprised of four members with a threshold of three votes to establish responsibility and to impose sanctions,” the letter states.

According to Dauber, most of Stanford’s peer schools require a simple majority among panels to establish responsibility, while Stanford requires unanimity among three panel members.

Under the previous system, four votes out of five were necessary to establish responsibility for the assault, so oftentimes a student walked away without punishment even though a majority (three) believed there was an assault. Dauber believes that the new system would make the problem worse.

“The unanimity requirement…makes us virtually alone [among our peer schools],” she said.

“Recommendation 2: We urge that the Faculty Senate establish a committee to recruit a volunteer pool of panel members, who should receive thorough training, and that this pool shall provide all Faculty Members for hearing panels,” the letter states.

“Recommendation 3: We urge that all Complainants, regardless of whether they proceed to a hearing, and regardless of the outcome of that hearing, should have the right to accommodations including counseling, housing, academic, and protective measures including no-contact directives,” it adds.

Dauber is concerned about providing accommodations to reporters of sexual violence because, according to her, Stanford could be breaking federal law under the Clery Act.

“It’s hard to tell if it’s just an oversight or if the intention of the University is to deny accommodations unless there is an active complaint in process,” Dauber said.

“No one [from the University administration] will answer my question,” she added.

Stephanie Pham ’18, co-founder of the sexual assault awareness group One in Five, noted that failure to provide accommodations for survivors also discourages people from reporting sexual offenses and therefore makes the Stanford campus unsafe.

“Stanford is one of the most, if not the most, unfriendly schools for sexual violence survivors in the country,” Dauber said.

“Recommendation 4: We urge the University to modify Stanford Admin. Guide 1.7.3 and the Draft Process to define sexual assault and manage expulsion similar to how it is handled in the Dartmouth policy,” the letter states.

As shown by the graphical comparisons included with the faculty letter, Stanford’s definition of sexual offenses is what Dauber calls “an extreme outlier” among peer schools.

According to Dauber, Stanford has defended the October 2014 change of its sexual assault and sexual misconduct definitions by saying that they were attempting to more closely follow federal and state law. However, she believes Stanford’s new definition instead violates California law, which requires colleges and universities to include affirmative consent as part of their definitions of sexual violence. Stanford only includes affirmative consent in its definition of sexual misconduct, not assault.

“It’s empirically not a true statement to say, ‘We changed our definition of sexual assault because we’re following the law,’” Dauber said.

Concern over time constraints

Dauber said that the idea for the letter grew out of a shared concern among the five professors.

She noted that the faculty had limited time to analyze the new policy and submit feedback. The policy proposal was released Nov. 9, and the deadline to submit feedback was less than four weeks later on Dec. 4.

“This is something that faculty would not have time to read and understand,” Dauber said.

Dauber was also concerned with the lack of opportunities for communication between students or faculty and the University administration.

“That there should have been a series of town hall meetings for students and faculty to discuss the findings [from the Task Force’s report] in detail,” she said.

Provost John Etchemendy Ph.D. ’82 hosted one town hall on Nov. 13, four days after the release of the policy proposal.

Dauber said that, given the limited time before the deadline for feedback, she and the other professors chose the four issues out of many they felt were most critical. They tried to request an extension of the deadline while preparing the letter, but the administration denied the request for extra time because the policy needed to go into effect the first day of winter quarter.

Lack of University response

When Dauber asked for an update a few days ago on the status of the community feedback sent in last month, she did not receive a response. She said she doesn’t even know whether the new policy has gone into effect at all.

In a second letter she sent on Dec. 6 directly to senior University counsel Lauren Schoenthaler, who was part of the Task Force, Dauber offered additional feedback. In particular, she outlined problems she has with the system of sanctioning precedent and provided potential solutions.

“I think that the panels need more guidance starting immediately as to sanctions, and we just do not have relevant precedent at this time,” Dauber wrote in an email to Schoenthaler accompanying her letter.

Dauber also included in the letter to Schoenthaler her thoughts on Informal Resolution, a process which would allow the parties involved in a report to draft a resolution similar to a plea bargain. She believes it is problematic because it is not very restrictive.

“The University has complete and total discretion over when they can offer Informal Resolution,” Dauber said.

She is also concerned that the system will create opportunities for “private side deals accessible to people with money and lawyers and not to others,” which won’t be able to be regulated. It also places pressure on both survivors and accused students to accept the conditions of a resolution, potentially putting campus safety at risk or undermining due process.

Dauber has not received a response from Schoenthaler or other administrators.

Community reception

On Dec. 2, Pham and One in Five co-founder Matthew Baiza ’18, sent an email to students informing them of the letter and highlighting the key points and recommendations. The information was also included in the ASSU executive update that was emailed to students the same night by ASSU President John-Lancaster Finley ’16.

“While this letter does not necessarily reflect the views of the entire ASSU, we personally think it’s important for students to read what faculty have to say, as we believe they’ve done a tremendous service to students by raising these very critical issues,” Finley and Vice President Brandon Hill ’16 wrote.

Ormenyi emphasized why she feels it is so essential that the University revise the new policy.

“Having worked in Residential Education from 2014 to 2015, I saw how important it was for faculty, student and staff collaboration in policy and programming changes,” said Ormenyi.

“The proposed implementation of the new Title IX policy and procedures is in stark contrast to this. And it does nothing to help the trust issue brought on following the sub-par climate survey on campus sexual violence,” she added.

Dauber felt the endeavor was successful because it helped to inform the faculty. She said many faculty members came forward to thank the group for writing the letter, and some copied the letter in their own feedback they sent to the University.

“People were just appreciative that someone took the time to read and analyze and think about it,” she said.

Contact Sarah Ortlip-Sommers at sortlip ‘at’ stanford.edu.