During an era when pop art and consumer culture dominated the American art scene, photography emerged as a means of both artistic expression and cultural criticism. “Wanting More,” a newly opened exhibit at the Cantor Arts Center, is an unassuming but conceptually powerful exposé of consumer culture in America in the mid-20th century. The exhibit also delves into the dual role of photography as advertisement and as fine art.

Much of American art in the 1900s focused on domestic objects and consumer goods, a fact that is perhaps best exemplified by the work of prominent American pop artist Andy Warhol. A superstar of the pop art era, Andy Warhol was known for incorporating imagery from commercial illustration in his paintings. His photographic work “Still Life,” on display in “Wanting More,” features a seemingly random assortment of domestic items emblazoned with the branding “Black Flag.” The juxtaposition of the jarring typeface and the docility and domesticity of the objects alludes to the ways in which mass marketing permeates everyday life.

Indeed, several of the photographic works in the exhibit feature common objects like containers and egg slicers that completely fill the frame of each photo. These works ask viewers to consider the aesthetics of the ordinary rather than the aesthetics of contrived paintings — a far cry from other exhibitions at the Cantor (e.g. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Sketchbooks Revealed”), which tend to be more painterly.

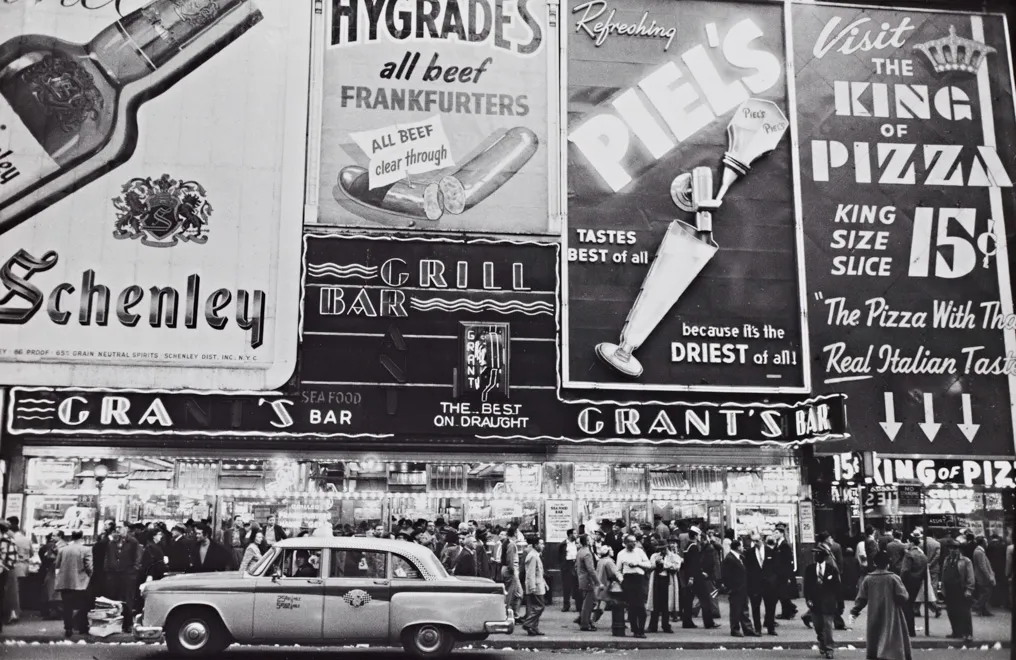

A key visual theme in the exhibit involves people in urban settings, where the figures in each image become secondary to sprawling advertisements plastered across building faces. Frank Paulin’s “Grant’s Bar, New York” and Elliot Erwitt’s “Southern Charm/Alabama,” both created in 1956, are two such works. The individuals in the photographs are hardly individuals at all; rather, they appear as nameless silhouettes against the white glow of billboards and neon signs.

One of the most haunting pieces in the exhibit, German-born artist Lotte Jacobi’s “Puppenkosmetic” depicts store shelves chock full of identical toy human heads. Jacobi’s employment of repetition furthers explores dehumanization in a mass market culture.

While not as immersive as some of its counterparts due to its small scale — both in terms of the physical gallery space and the size of the works on display — “Wanting More” is a strong commentary on consumerism in the 1950s. Though not outwardly hostile towards mass media and advertising, the exhibit suggests that these ideas have become irrevocably intertwined with our lives. In doing so, “Wanting More” prompts viewers to formulate their own opinions about this era in American history and its implications for today’s fast-paced society.

Contact Eric Huang at eyhuang ‘at’ stanford.edu.