The last time I talked to Emma Mathers ’18 in person was fall quarter 2015. We were both stressing over our organic chemistry problem set. On the other side of the world, the Syrian refugee crisis had exploded into an international issue — the pictures of wet, desperate Syrians in life jackets cycled through CNN.

The next time I heard from Emma was in December. She had posted a quick message on her Facebook: She was taking a leave of absence from Stanford. Tired of seeing the news about the Syrian refugee crisis and feeling helpless, she booked a one-way flight to the tiny island of Lesbos, Greece. She wrote on her Facebook, “I’m scared, but the refugees are more scared.”

Emma and her roommate Clara, a British girl she met through a volunteer Facebook page, kept their Facebook/blogs updated periodically. In the beginning, their optimistic posts included pictures of the cute apartment they rented above a flower shop in Molyvos, anecdotes about the refugees they befriended and selfies in front of the harbor with the cerulean Mediterranean in the background. They reminded me of the Stanford stereotype — students caught firmly in their belief that they are capable, nay, destined, to make the world a better place.

Slowly, things changed. Emma and Clara ran out of funds to keep their lease on the flower shop apartment. The sad endings to the anecdotes began to outnumber the happy ones. Clara returned to the U.K. The Facebook updates stalled.

Clara wrote on her blog, shortly after leaving Lesbos: “I’m sorry, because no matter how many of us try, no matter how much love we do it with, no matter how many sandwiches we make or how many shoes we hand out, the border is still closed and people are still being left to rot on the other side.”

*****

The most recent time I spoke to Emma was over a tenuous Skype connection. She was in London where she was staying at Clara’s flat.

The first question I asked her was “Why?” Why would she drop everything to travel solo to Greece?

“It wasn’t something that I had really planned out. I’ve always cared about things, but this was the first time I had really taken action. I was absolutely terrified,” she laughed. “I didn’t think I was strong enough.”

In Lesbos, Emma worked with a Greek NGO called Starfish. Her job was receiving the refugees on the beach, the ones who made it from Turkey to Lesbos on the rihlat al moot (“route of death”) after shelling out $1,000 for a ticket on a rubber dinghy.

“It was actually a very time-sensitive, high-pressure job. Especially when we got there in January, we had a lot of cases of hypothermia.” Emma choked up telling me about watching the Coast Guard pulling out a 6-month-old baby from the freezing water. The baby later died in the hospital. “There was nothing they could do,” she said, voice breaking.

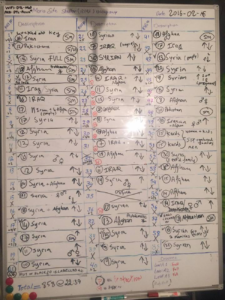

Emma also worked with Starfish at Moria, the main UNHCR registration center on Lesbos. “All the refugees had to come through it so they could get their registration documents,” she explained. When the EU borders were still open, the documented refugees could then take the ferry to Athens and then move on into Europe.

“Usually it was a quick transit time, only three or four nights, but I helped to run the accommodation allocation system. So we distributed tents, plastic huts and beds as well as food, blankets, dry clothing and shoes.”

Next, on March 16, Emma started work in Idomeni, a small village on the Greek-Macedonian border where 11,000 refugees were stranded after Macedonia closed its borders. There, she primarily worked with Lighthouse, a Swedish NGO. She also assisted Doctors Without Borders and Save the Children with food and clothing distribution. The goal of Idomeni, says Emma, was to make it a much more “sustainable, long-term living arrangement.”

“I helped to build a school, a little wooden hut, and we found two refugees who were actually teachers back in Syria. We had math and Arabic classes every morning, and we got donations for supplies.” Emma beams through the fuzzy image on my computer. “All the kids had their own little notebooks and pencils, and they were so excited to come to school.”

Emma tells me that she spent much of her time playing with the children in Idomeni — “bubble and jump ropes and hula hoops.” Of the 4.8 million registered Syrian refugees, half are children. Many children are traveling alone and are extremely vulnerable; Europol estimates that 10,000 have gone missing, preyed on by organized trafficking groups.

“Idomeni was 50 percent children,” she emphasized, “so there were a lot of really bored kids who needed entertainment. You don’t think of playing with kids as being valuable, but honestly … it was pretty meaningful for them, I think.”

“These are little kids who had already been through so much, and now they’re waiting at the border for months and months,” she said. “There’s absolutely no mental health support at all. They have it for volunteers, but they don’t have it for refugees.”

Another big project was setting up a “clean and safe” mother-baby space in the sea of tents at Idomeni, “for the mothers to breastfeed and wash their babies.” She tells me about the baby changing area they made, and how they stocked it with pillows and blankets, so that it was “really cute and cozy.”

Emma positively lights up when she talks about the people she has met in the refugee camps—her “favorite thing to talk about.” One of her “best friends” is Michael.*

“He’s 16, he’s from Damascus, and he likes to play League of Legends and he used to be on [his school’s] swim team,” Emma recalled. They met in Idomeni. Michael and his family had fled to Turkey after their house was bombed two years ago, and eventually made it to Idomeni. “When you’re hanging out with him, it’s easy to forget that you’re in a refugee camp because he acts like a normal 16-year-old kid. He reminded me a lot of my little brother, and he started calling me his sister.”

Emma was there when Michael’s family managed to make it through the “ridiculous” asylum process, which involves trying to beat out 60,000 other refugees, all attempting to Skype into the UNHCR asylum office during the allotted hour a day. Each asylum appointment takes half an hour, so at most, only two families are granted asylum per day.

On her last day in Idomeni, Michael’s family, huddled around a single smartphone, scored a coveted asylum appointment. They’re now waiting to hear back about which EU country they will be relocated to. “It’s fantastic,” she gushes. “It’s one of the very few success stories and I’m so happy it happened to his family. I cried so much.”

Emma’s stories are infinite. There’s the teenage boy, alone in a refugee camp, whose father was killed in Aleppo months before, and who attempted self-immolation after discovering his mother had been killed too.

There’s the 18-year-old Afghani girl Emma had met at Moria immediately after she had been rescued from the sea. She and Emma reunited at Idomeni weeks later, where the Macedonian police had returned her after her family tried to cross the border.

There are the teenage brothers on the run from Afghanistan, who gave Emma and Clara the rings off their fingers as a thank you for two water bottles.

Finally, there’s the young family of seven that Emma had helped at Moria to get ferry tickets to Athens. At Idomeni, the four-year-old daughter remembered her and shouted her name: “It was bittersweet, because they never made it past [the Macedonian border before it closed], and they’re still sitting there at that border.”

*****

Given a fracturing EU recovering from terrorist attacks, a debt-ridden Greece ill-equipped to handle thousands of refugees, and thousands of refugees who have drowned, the EU chose to make a controversial “one for one” deal with Turkey. This topic was the only time Emma got truly angry in our interview.

“All refugees arriving in Greece after March 20th will be detained in Moria and deported back to Turkey because Turkey has been deemed a safe third world country by the EU,” explained Emma. “In exchange for each refugee deported from the Greek islands, there will be one refugee taken from Turkey and resettled in a EU country by legal means.”

To me, the deal sounded great. It dissuades refugees from making the risky and dangerous sea journey. Emma countered, “It’s actually terrible, because there are so many instances of police brutality.”

“I’ve seen scars on kids faces from the Turkish police just beating them. The Turkish people are not very accepting of the refugee population. The working conditions for refugees are horrid—there’s not enough money to live. The kids can’t get into the Turkish school system because it’s not in Arabic and there are no catch-up programs for them to learn Turkish.” Scarily, Emma told me of reports that Turkey has begun to deport refugees back to Syria where they are likely to be killed.

The EU-Turkey deal gives refugees a second option to apply for asylum in Greece instead of being deported but the problem is that “they don’t have enough asylum officers working to process the applications, so they’re not giving people the opportunity to apply for asylum.” Many people sent back are not even told of their rights to apply for asylum.

“It makes you feel really powerless,” Emma said, “because everything we did inside of Moria to make it a more humane place to be is completely destroyed. All NGOs have been kicked out. It’s at double capacity, so there are kids, old people, sick people sleeping outside.”

Moria, the UNHCR headquarters where Emma had volunteered, was a former prison which was convertedinto a refugee camp. Now it is a detention center, run by the military and full of 4,000 refugees waiting to be shipped back to Turkey, refugees who were stranded when EU borders closed. The Nation compared it to Guantánamo.

*****

Recently, the Telegraph published a stark headline: “The migrant crisis will never end. It is part of the modern world.”

And yes, we have yet to find long-term sustainable solutions to control the migration that will always result from conflict. But it is important to remember these people and these true crises that happen outside of our Stanford/American bubble, despite the fact that it may not be the attention-grabbing breaking news.

The media cared about the refugees until it didn’t. People cared about the refugees until they didn’t. Google Trends shows us that Google searches for “Syrian refugee crisis” have dropped 89 percent from their highest point in 2015. Like the vicious cycle of awareness campaigns on campus, the Syrian refugee crisis illustrates how our society tends to move on to the next big disaster without solving the crises we already have, a “globalization of indifference.”

Emma’s story reminds us that while the American media and people turn their attention to the next big thing, the refugees have no choice. They do not get to escape their situation.

They can only hope for a better life an ocean away, across barbed wire fences, on the other side of a lucky Skype call.

*****

Emma traveled to London about a month ago, after her 3-month Schengen Zone pass expired. She’ll have to wait another three months if she wants to return to Greece.

She is traveling to Bekaa Valley of Lebanon next, where “most of the refugees are waiting to go back to Syria after the war ends.” Clara and another volunteer friend, Paul, are joining Emma on their self-funded trip. I marveled at her nonchalant attitude when she said that she’ll go “wherever help is most needed,” no questions asked.

I couldn’t help but wonder: how do you deal with all of this — the trauma, the despair, the pervasive helplessness? For a moment, Emma looks vulnerable, like the 19-year-old girl I know. “You work double shifts and night shifts and you just can’t work if you’re trying to take this (the refugee crisis) all in at the same time,” Emma explained.

“Honestly, I think it will hit me more when I go home. I’ve been able to make some close connections and stay in touch with some of the refugees I’ve met. Obviously I can’t experience what they have, but I’ve taken on some of their pain, and I’m so worried about all of them.”

But you’re a Stanford student, I thought. You’ve done your quarter of service. You could come back to a cushy existence in a world of palm trees and all-you-can-eat dining halls. “Why do you stay?”

“Because I’ve gotten way too attached,” she answered. “It’s personal for me now — I have so, so many refugee friends that I care about. I don’t think I’d ever be able to forgive myself if I came home since there’s so much work to be done and the situation isn’t improving in the foreseeable future. I feel like I owe it to all the amazing people I met to keep going because they keep going — I mean obviously they don’t have a choice, but these people are just the strongest and most resilient people.”

“What’s so amazing is how generous they are, even after all the horrible things they encounter. They’re still so loving. They’ll ask you to sit down with them for tea. They wait in line for an hour to get their food [but] they’ll offer you all the food that they have.”

When I ask Emma when she will come back to the Farm (“Probably all my friends hate me because I’ve been awful at responding to messages,” she interjects), she says only, “Maybe in the fall.” She pauses. “More than anything, I just want to come home and have [the crisis] be over. I don’t want to feel like I need to be here anymore.”

*Name changed for privacy. (Many of the refugees have family back in Syria who could face retribution.)

Contact Samantha Wong at slwong ‘at’ stanford.edu