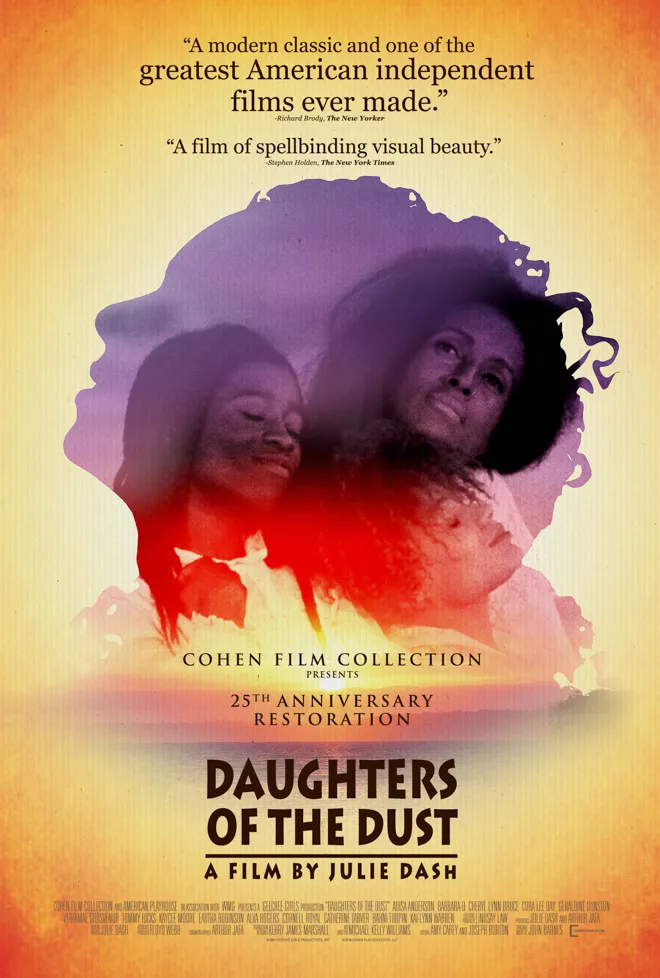

This December, a pillar of American cinema is being re-released. “Daughters of the Dust,” the 1991 debut of independent director Julie Dash, has been restored and will be distributed by the Cohen Film Collection in theaters across America. In this era of Black Lives Matter, Beyonce’s “Lemonade”, Kendrick and the return of D’Angelo, the re-release of Dash’s film deserves to be greeted with cheers and trumpet blasts. “Daughters” is a seminal, visionary, challenging work of art — a masterpiece that every American should see.

The film traces the intergenerational trials and tribulations of the Peazants, a Gullah family who are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans. The Gullahs live along the coast of South Carolina in 1902, at the dawn of the 20th century. Because of their geographical isolation, the Peazants have preserved the traditions, language and arts (food, music, dance) of their African ancestors: the Ibo, the Yoruba, the Kongo. The film has a plot (the family is trying to move up North), but one that is presented in an off-center, nonlinear fashion. “Daughters” hazes by in dreamlike, colorfilled shots, emotions, sensations. Dash — who has no cinematic parallel, whose only direct inspiration is the shared cultural heritage of all African-Americans — keys in on the experiences of the black women of the Peazant family. It’s for these reasons (its laser-like focus on the lives of black women, its avant-garde imagery) that “Daughters” has been seen as a major influence on Beyoncé’s equally visionary visual album of this year, “Lemonade.”

Dash was part of the “LA Rebellion,” a collective of predominently black filmmakers who graduated from UCLA’s film school, and who, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, made a series of emotionally astonishing independent films (“Killer of Sheep,” “Bush Mama,” “My Brother’s Wedding,” “Bless Their Little Hearts,” and Dash’s own “Illusions” and “Daughters of the Dust”) centered around the lives of African-Americans, usually in the inner city parts of Los Angeles. Alongside directors like Charles Burnett and Haile Gerima, Dash forged a new independent aesthetic and a new direction for filmmakers of color who were shut out from fully realizing their artistic visions within the Hollywood studio system.

“Daughters” recently played in its restored version at the 39th Mill Valley Film Festival. The Stanford Daily sat down with Dash to talk about her film, “Lemonade,” depictions of slavery in film and much more. A living pioneer of cinema, Dash is engaging, lively, passionate—and has a lot to teach us about the direction in which cinema is heading today.

* * *

The Stanford Daily (TSD): How does it feel to have “Daughters of the Dust” receive the restoration and release it deserves after nearly 25 years?

Julie Dash (JD): Twenty-six! And we shot in 1989, so that makes it even longer! Were you even born in ’89?

TSD: No, I was born in ’96.

JD: See, I… Wow. Whoa.

So, I’d be curious to know what young people think about it, because it was very experimental when I wrote and shot it back in the day. But it’s all good. I’m very excited about the restoration, because now we get to see it in the way it’s supposed to look. We just flat ran out of money when we were working with analog film, as opposed to digital. Back then, we had $20,000 for one answer print and didn’t have any money for more. So we needed to correct the colors, to get back to the quality of the work-print we were editing. The released film never looked like the work-print. Now it does. It’s in the digital space now.

I’m just happy, because I forgot you can look at the faces of the people, the robust colors.

TSD: Yeah — the only copy of the film I could watch was an old, faded, out-of-print DVD from 2001. Even in that quality, though, it blew me away.

It got me thinking a lot about the way we form a canon of “great films,” and how that is totally dependent upon availability. Even now, filmmakers of color and female filmmakers don’t have the same privileges as white male filmmakers have in terms of getting their films out there —

JD: Right, right —

TSD: — and the struggles to get your film out reminded me of another film from a black female director, which is only now starting to get the canonical attention it deserves: Kathleen Collins’ “Losing Ground.”

JD: I knew Kathleen Collins! And absolutely. She died way too young. I was in my twenties, and she had just graduated from the Sorbonne, was fluent in French, had studied in French. And here I am, coming out of New York from the projects. And she’s just here like, [fanfare noise], “Black Woman Filmmaker!” Before her, the other filmmaker to whom I looked up also passed away too early — Sara Gómez. She was a filmmaker at the Cuban Film Institute who did amazing feature films. It was a hard way to go for everyone. Neither of their films got distribution in their lifetimes.

TSD: It’s a tragedy. Yours has, though, thank god. And certainly, with the release of “Lemonade” by Beyonce —

JD: Haha, yes!

TSD: — it’s put “Daughters” back on the map!

JD: Yes! Thanks to “Lemonade” and Solange [Knowles]. “Lemonade” is a triumph. Because I’m the type of filmmaker that likes to decipher stories. Now, yes, I like to watch things on television that are just straightforward. But then other times, I want more. And “Lemonade” was exactly that. And it was so culturally specific. I was like, “Oh… okay! I get you!” With the music, and the articulated movements that are very spiritual. It’s very into expressions of ritualistic behavior. That’s where film is going, I think… Well, of course it is! It’s been going that way. [laughs]

TSD: In the case of both “Daughters” and “Lemonade,” it’s a case of instinctual feeling and gut emotional response to pure and complex images, feeling something through the coded, culturally specific richness of the image. It isn’t presented to you on a silver platter, with a note saying, “This is what it all means! Here is the easy answer!”

JD: It’s visceral. Sometimes you know it viscerally, before your mind says, “Oh! I get it!” I like that.

TSD: Let’s talk about the genesis for “Daughters of the Dust.” Who were you reading, which artists were you looking at?

JD: Okay — so the writers would always include Toni Morrison, Toni Kay Bambara, Alice Walker. The poets Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Jane Cortez. The films of Satyajit Ray, like the Apu Trilogy [1955-59]. The Russian filmmakers: Parajanov [“The Color of Pomegranates”, “The Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors”] and Andrei Tarkovsky [“Andrei Rublev,” “Stalker,” “Ivan’s Childhood”].

For me, you don’t have to exactly “know” the culture to get it. Sometimes, it’s about the spectacle of being right in it, with stuff going on all around you, you start getting it little by little, and then you go, “Ah … yeah … ooh, I never thought of it that way!” That’s visual poetry.

“Daughters of the Dust” is the cinema of ideas. I was always asking, what if? What if an unborn child could come forward and help mediate a problem between mother and father? What if a great-great-grandmother could not physically travel to the future with her family? What does she do? She offers her “Hand” [a talisman that the family matriarch always holds on to throughout “Daughters”].

Things just started falling into place when I wrote about the Hand that she makes. I didn’t even know it was called a “Hand.” But the concept of the Hand was: “Take my hand, take this compilation of the moss and the Bible that you love so much, kiss it, and take me where you want to go.” The things I wrote just fell into place, naturally and spiritually. And it came out of my combinations: “Okay, let’s pull in Islam, let’s pull in Christianity, let’s put in the moss.” Let’s pull all these things together, because it’s synchronicity.

TSD: Yeah, it’s like a masala, mixing cultural strands together —

JD: That’s what it is! And that’s who we are. And that’s what this New World is. And it’s especially reflected in the music of “Daughters of the Dust.” It’s New World music. Me and John Barnes — the composer, who had only 10 days to write and record everything, who went into this trance while doing it — came together and asked ourselves, “What is New World music?” In a Hollywood movie, they always try to put in some old harmonica or banjo. That’s — not — it.

So what is it? Okay. Let’s say you were traveling in the Middle Passage; below deck, what do you hear? Who was above? Some Irish sailors, British sailors — but you would also have Pakistani and Indian sailors, too. Iran. Persia. And so John put together this crazy team: a Pakistani drummer, an Iranian who could play the santur, a shakuhachi flute player (because the ship, at some point, must have stopped in Japan and picked up a shakuhachi). So we mixed all of these world sounds into “the New World sound.” That’s why the music sounds so different. We didn’t use anything that Hollywood would use.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m not putting Hollywood down, but they just love to press the easy button all the time.

TSD: And your film isn’t working on a simplistic level where it’s neat, easy, tidy to get the first time. This is a film that is emotionally overwhelming, and that you need to watch again and again —

JD: Right, layers and layers. Because a lot’s happening.

TSD: I was very moved and interested by the unconventional way you depicted a Black past, in particular the history of slavery in America. You don’t use familiar images or tropes like cotton, the chain, the whipping scars. Instead, you bring up indigo, and the stain of indigo on a Gullah woman’s calloused hands.

JD: Right. Exactly. You got it. Because my feeling is this: Having grown up watching “Gone with the Wind,” you see somebody getting whipped, you become anesthetized to images of slavery. Especially the sanitized ones, like in “Gone with the Wind” or in the old “Roots” from the ’70s.

But my question to myself was: What could I find to depict slavery in a new kind of way? Indigo! That was poisonous, of course, in real life, it would have washed off by then, by 1902. But it was the stain of slavery, so I’m working with the metaphor. And it was the processing of indigo that initially made the American colonies so rich. Because every uniform in Europe was blue — where did that blue come from? Indigo. From Barbados, and from South Carolina. Indigo and rice were the cash crop long before cotton, but everyone thinks “cotton” because everyone refers back to — what else? — “Gone with the Wind.” Cotton-picking. The house mammy.

Now, it wasn’t necessarily to subvert the Hollywood images and models … but, yes — offering something new.

* * *

TSD: Do you have any advice for young filmmakers of color and female filmmakers trying to make films from ideas that are being rejected by producers?

JD: Nothing much has changed in that region. They just have to make the films that they want to make. It’s always nice to go pitch a story — that’s part of the growing experience, too. But if they can’t get money that way, they can always turn to Kickstarter, Indiegogo, whatever and wherever they can. Just start making a film that you want to make, even if it’s a short. But don’t let anyone ever tell you that there’s no audience. Because that’s a lie; just travel to international film festivals to see why that’s a lie. That’s where we started in 1979: Cannes, Munich, London. Across the world, there are people interested in the movies emerging filmmakers want to make.

You can’t listen to the curators of culture. They make arbitrary judgments: “Oh, there’s no audience. You can’t sell that overseas. It’s too complicated. This is not accessible.” I was told after Sundance that “Daughters of the Dust” was not a real African-American film… Well, who am I, then? Where did I come from?

TSD: Another problem is that the producers and critics evaluating these kinds of movies are predominantly white males—

JD: —And if you show them things they don’t already know, they freak out and go, “This can’t be happening! I’ve never heard of Gullah or Geechee people. No one wants to see that. Gimme a good ol’-fashioned slave whippin’ film!”

But even if they’re not that — Melissa Harris-Perry once told me, “You don’t have any white people in the film.” But it never crossed my mind! That was another film. If you have white people in film and you’re kicking them and calling them names, they’ll be happy, because they’re in the film. But if they’re not in the film at all, they’re like: (panicked expression) “You don’t like me?” It’s like, no, I was telling this story about these people on an island. You weren’t over there! You know what I mean? Those curators of culture — they were wrong about a lot of things, and they continue to be wrong.

But I always say, if you want to heal the ills of the world, it can be done through film. Anything and everything. If people see themselves represented in ways that they’re inspired me, it doesn’t have to be (picks up nearby water bottle), “He invented this Aquafina! So you should like him!” NO! The real stories with depth and complexity. Characters with foibles and strength. If you see yourself on the screen, participating in all of this, you have hope of a future.

I grew up in the Queensbridge housing projects in Long Island. (Nas came from there.) Drugs, violence, it was one of the roughest projects in the city of New York. No one really saw themselves existing after age 26. If you were 13, and you said, “Yeah, I guess I’ll be 26.” You don’t really have a clear or a future path. Me, I wanted to be in the roller derby. Why? Because back then — in the 60s — roller derby queens were all the rage. They were mostly Puerto Rican and Black, had pink hair, big old scarves. And they had agency. Made a lot of money. Rough and tumble. I was like, “Yeah I can do that.”

But it’s just all about seeing yourself not being pathetic. Or not being that hero that no one believes. Or not just being the martyr. I learn that from my daughter. She was like, “Don’t talk to me about being like people on that wall. They’re all dead.” Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers, JFK — all shot or dead. No one wants to be that. No one wants to see these dead people — and that’s the end-all you’re supposed to be inspired to be?

TSD: You know, it’s interesting, you have such a diverse and wide range in your work. Like the other directors of the L.A. Rebellion, you work across different types of media: music videos, TV specials, Lifetime or BET movies of the week, educational 1-hour videos, short films. And I was struck by an interview where you said that after “Daughters,” you had a lot of requests to keep making that same kind of story, as if to cash in on it.

JD: Yeah, they kept giving me these Civil Rights/Klan movies. I don’t think people really understand me. I like to do different projects. I’m a filmmaker, I’m a storyteller, and I’m always looking for new ways to tell a new story.

For me, “Daughters of the Dust” was science fiction. It was a voodoo movie. And an opportunity to show sci-fi, or speculative fiction which I’ve always loved, in a new way.

TSD: Afrofuturist, even!

JD: Yes! There were Afrofuturists before there were people on Twitter talking about it. There were Afrofuturists back in the ‘30s…hell-ooo! And I was friends with the authors Octavia Butler and Nalo Hopkinson and Tananarive Due. Yes. I’d love to get money to do real Afrofuturist stuff. But people locked me in on “Daughters of the Dust.” I do different things. I even do cheesy stuff. Have you seen “Incognito”?

TSD: I haven’t.

JD: (laughs) Okay, maybe that’s a good thing! It was another one of those 16-days feature films, you know.

* * *

TSD: You’re part of the so-called LA Rebellion, a group of filmmakers who come out of UCLA in the 70s and 80s to make these cutting, independent masterpieces. What was that atmosphere like, working alongside people like Charles Burnett and Haile Gerima?

JD: Well, I got there just as everyone was leaving, like Haile, Charles, Larry Clark. They were all pretty much finished, but they hung around for like a year. We got to view their films, and talk and interact with them. I worked with Billy Woodberry and Barbara McCullough. We were there for four years for graduate school. There was a lot of overlapping and working on each other’s films. It was a great environment, because I graduated from CCNY (The City College of New York), then to AFI (American Film Institute) for two years. And at AFI, it was just so frustrating, and I used to hang out with the UCLA people because they were making films more radical. Larry would say, “I’m going into the desert next week, will you come and do sound for me?” “In the desert? Okay.” I guess people are still doing that, but people were passionate about the stories they wanted to tell. They weren’t traditional stories, but you wanted to be a part of it because you wanted to be a part of something, and you know you could learn and hone in your skills.

So it was just dedicated film students who lived at UCLA. Sleeping on the floors in the editing room. And everyone complained a lot: (mopey voice) “I just want to graduate and get outta here, hate this place.” But when you look back at it, you can see there was a collective of people working together. But we didn’t have that name “LA Rebellion” given to us until years later. Clyde Taylor wrote a thing on us, and it was just UCLA filmmakers, different from the USC or AFI filmmakers, because they were being groomed to go right into Hollywood, and they did. My contemporaries at AFI were Mimi Leder, Amy Heckerling [“Clueless”, “Fast Times at Ridgemont High”], Marshall Herkovitz and Ed Zwick [“Blood Diamond,” “Glory”, “The Last Samurai”]. We were all there at the same time, and they all went straight into Hollywood. There were no open doors for me.

TSD: You teach. What’s the atmosphere like, to you, teaching on campuses today, as compared to what you went through at UCLA?

JD: When I came in to UCLA, it was post-hippie and post-protests and radicalism. Everyone was still trying to find themselves, but those elements were still there. Hippie culture quickly turned to punk rock. It was fascinating to see people shift identities, and be whoever they wanted to be. There was no criticism there, and when I saw someone like my friend Monona Wali, I’d think, “Wow. I’ve never seen a punk Indian before. That’s so fascinating!”

Today, on campuses, post-Spike Lee, post-Ava DuVernay, a lot of people just want to be famous — which is not a bad thing. It depends on the campus I’m on. Some people — emerging filmmakers of color — do not want to be recognized as a filmmaker of color. Some of them do not want to be recognized as a “woman” filmmaker. And some just want to be famous. Some people, though, are really radical, like we were back in the day, in just wanting to tell stories.

But back then, there was no one that we could point to and say, “I want to be like this person.” Now there are people you can point to, saying, “I want to be like Spike, like John Singleton, like like Ava.” People start honing in on those role-models. They’re now more clearly defined. When we were at UCLA, the idea, the notion of wanting to be a filmmaker, was kind of absurd. It was like, “Well, you’re jumping head first into something where you have no future.” And we were like, (mischievous smile on face) “Yeaaaaahhh … I have no future … yeah!” Gotta like that! Just like some kind of “Blade Runner” radical.

TSD: But someone has to forge the path, someone has to be the one to get it started, and you and Charles and Haile and all the other members of the LA Rebellion were the ones that dug that path.

JD: But we weren’t thinking about being a pioneer, being a role-model. We were just like, “We have no future. We can live with that.” That’s before you have a family or children. There was no pressure. With “Daughters of the Dust,” I didn’t feel nothing but to sell this story. It was all some grand experiment. I was like, “Hmm, if I tell it this way, or that way …” No pressure.

And that’s what I tell my students. When you’re in college, or graduate or undergraduate school, stretch out. See who you are. Find your real voice. There’s no pressure, you know? You just have to pay your tuition, which (raises eyebrows) is crazy now.

One of the benefits we had from the protests before we got to college was that I didn’t have that kind of tuition bill. I did not have to pay $30,000 or $60,000. I’m a child of affirmative action. And it worked! So I didn’t have those same pressures on me: “I have to graduate, I have to get a good paying job, I have to find a job at Universal Studios directing a big project.” I was just like, well, good luck with that.

Being a filmmaker is still a political act. When people aren’t buying what you’re selling, or supporting you in advancing, you have to understand that it’s because they’re giving you a public voice. And traditionally those voices have been reserved for a very select few. Unless they know for sure what you’re going to say, you have to toe the party line. And I think a lot of young people don’t quite understand that yet: the Power that blocks them, the Power that they’re reaching towards. And they can’t understand why they’re not getting work. It’s a very powerful situation, and God bless you, and keep reaching for it. But … you know.

People say to me, “Oh, I have wonderful idea for a reality show.” And you go, “(taps fingers) Oh …” Why should they give you the opportunity to make millions without owning you? You’re not related to them. I always tell people to read books and watch the connections. In that environment, everyone’s related some way. Even if it’s a fifth cousin, or whatever, it’s prior relationships. Even today, when you see people all of a sudden spring forward, it’s because they have the support. Someone’s quarterbacking for them. They have an angel guiding them, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But sometimes, that’s just what they need. Ava’s become an angel to a lot of people. With “Queen Sugar” [a TV drama created by Ava DuVernay for the Oprah Winfrey Network], she has, in six months’ time, done more than Hollywood has done in 100 years, by hiring black, woman, Asian woman directors.

* * *

“Daughters of the Dust” opens December 2nd at the Landmark Opera Plaza in San Francisco and the Landmark Shattuck in Berkeley.

Additionally, several of Dash’s films are available to view on campus at Green Library’s Media and Microtext Center. These include “Daughters of the Dust,” “Illusions” (1982), and a little-known but just-as-radical-as-“Daughters” short film called “Praise House” (1991), which can be best described as an experimental short tracing the history of African and African-American Woman through song, folklore, and dance. Scurrilous, active, a combo of African rhythm dance and a fluid God-like liquidy camera, Draw or die is the moral of Dash’s “Praise House” story, boldly explicating how black women must create their own stories to combat the cartooned stereotypes that today exist of them in Hollywood. “Four Women” (1975), another dance short-film set to the titular Nina Simone song, is available to view online here.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.