From Brexit to the rise of Marine Le Pen in France to Donald Trump’s election, the rise of populist movements has been at the center of international news in the past year. Stanford professors Francis Fukuyama and Josiah Ober say that technocrats’ mistakes in the past have led to the rise of populist movements.

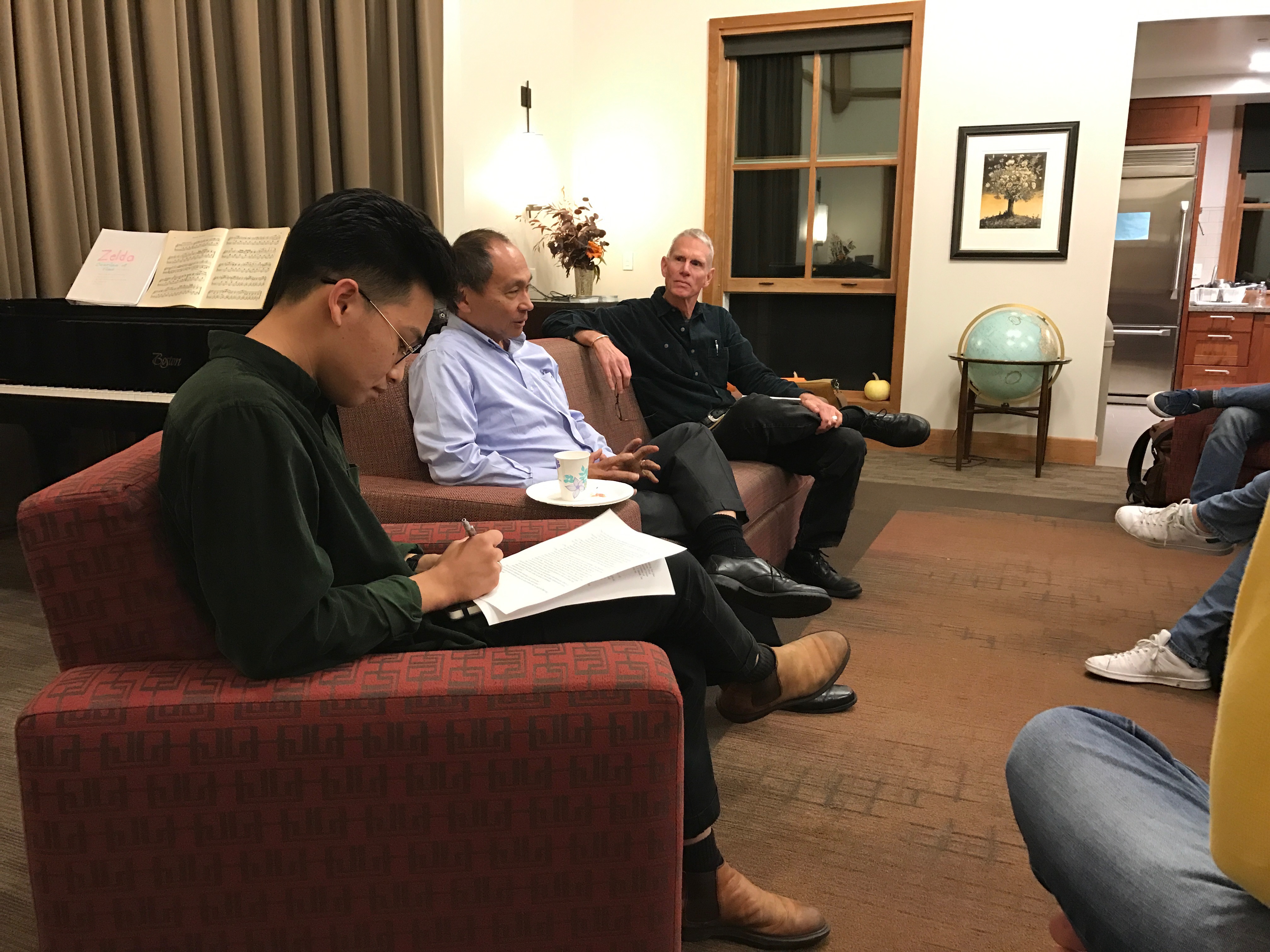

Fukuyama and Ober discussed the topic at a conversation titled “Does Populism Democratize Democracy?” attended by members of the Stanford community on Monday evening.

Francis Fukuyama, the Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) and professor by courtesy in the department of political science, has focused much of his writing on issues concerning democratization and the international political economy. Ober, the Mitsotakis Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, works on historical institutionalism and political theory.

Organized by the Stanford Political Journal (SPJ), Ethics in Society and the Ng Humanities House, the conversation between Fukuyama and Ober covered topics from disinformation and post-truth, to citizenship and immigration, to class divides and campaign finance in U.S. politics. Both noted the rise of illiberalism in modern day democracies and discussed its origins.

“The idea of this event was to have a conversation that was interdisciplinary and interdepartmental,” said SPJ editor-in-chief Truman Chen ’17. “It just so happened that populism and democracy were terms that were often thrown around at the time of the 2016 election, and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to bring together authorities from different disciplines and perspectives to finally add to the conversation.”

Both professors believe populism has had a mixed effect on democracy, especially in the recent U.S. presidential election.

“American populism is a proper function of democracy,” Fukuyama said.

Fukuyama continued to explain that a significant portion of the U.S. population not adequately represented by either side of the political spectrum, with that portion being the white working class. This exclusion, Fukuyama and Ober believe, led to the rise of Donald Trump.

According to Ober, a populist movement does not allow an opposition, as it follows the assumption that the people are always right.

Fukuyama went on to question this principle: “Do people know best? Could the involvement of each and every citizen in every issue result in better public policy? I think not … I don’t think anybody trusts 535 idiot members of Congress to make decisions on monetary policy,” Fukuyama said, citing the Federal Reserve System as an example that turns away from populist influences.

In fact, Josiah Ober concluded, “Populism is a threat to democracy because it is tyranny.”

On the issue of illiberal democracies, the two agreed that technocrats’ mistakes in the past have prompted the rise of illiberalism. In addition, social media has made it easier for misinformation to be spread. Fukuyama believes that certain countries like Russia have mastered the ability to design trolls to spread incorrect information and undermine people’s confidence in existing institutions.

“When the press was restricted, misinformation was often countered by good media,” Fukuyama said. “However, the rise of social media shows the corrosive effect the internet has in affecting the rise of such ideas. I don’t know what we can do to solve this problem.”

When asked about campaign finance, Fukuyama and Ober thought similarly. Both agreed that there is too much money is involved in politics.

“Big firms like Goldman Sachs have far too much influence in Washington than they should. The moment congressmen enter office, all they do is raise money, and this affects the way they vote,” Fukuyama said. “Our Supreme Court has argued that money in politics is a form of free speech and is protected by the First Amendment. The only way to regulate campaign finance would be to get a new Supreme Court.”

Ober concluded the evening by raising a few questions about the ruling class: “The big question that we have no answer for is, ‘What if we want to revoke the authority of the entire ruling class?’ The answer to this question goes back to the beginning of the U.S., where Jefferson imagined a constitutional convention every few years. However, that didn’t work out.”

Ober also stressed why he believe people should be well educated about and involved in politics to prevent the ruling class from exploiting its power.

“An individual is promoting tyranny if he is not participating in the democratic process,” Ober said.

In an interview conducted by The Daily, both Fukuyama and Ober stressed the importance of Stanford’s ability to educate students on politics.

“Stanford needs a core curriculum that teaches people basic facts about their political life, about global democracy, how citizens make choices, how political systems work,” Fukuyama said. The last time Stanford debated this was in the 1990s, and they rejected the idea. I think that it was a big mistake.”

“Stanford should be pushing students to get exposed to such topics,” Ober agreed.

Contact Vibhav Mariwala at vibhavm ‘at’ stanford.edu.