If you complain about chemistry, major in biology or human biology, petition for 22 units twice a year, get aneurysms thinking about our disintegrating healthcare system, and/or wear strangely wet scrubs to class, you’ll inevitably be asked:

“Are you pre-med?”

Depending on how many years you’ve been at the grind, your affirmative will either be enthusiastic, despairing (because they’ve discovered your deepest darkest secret and will judge you to be a soulless monster with a really good GPA) or nonchalant (because you’re totally not like all those other high-strung pre-meds, because you’re, like, just so chill).

But there’s also the confessional “I used to be pre-med, but…”

Medical professionals, students and laypeople alike agree that the path to becoming a doctor is long and hard. They all tell you to think hard and think twice about whether all these sacrifices will be worth it, and once you’ve done that — think again. And one of the biggest hurdles is getting into medical school in the first place. Everyone has their reasons for dropping out of the pre-med track. In the wake of the many tears, regrets and headshakes of disappointment from every entity in the cosmos and your mom that ensue from that decision, we need to take a harder look at why pre-med is so notoriously difficult.

What lies behind that “but”?

“A competent knowledge of chemistry, biology, and physics”

Stanford advises its pre-medical students to take “2 years chemistry with lab, 1 year biology with lab,” and “1 year physics with lab.” They note that “some medical schools may require math and English and some of the sciences require math as a prerequisite.” The addition of a behavioral science component to the MCAT (Medical College Admissions Test) in 2015 encourages students to take an additional course in sociology or psychology.

This translates to six or seven chemistry courses, five biology courses, three physics classes, two writing classes, and two to four math classes (including statistics), totaling from 18 to 21 pre-med courses, or 115 to 130 units. You can’t major in pre-med, as they say, but with that many units, you could conceivably get degrees in Human Biology (min. 81 units) or Biology (86-102) with Japanese (min. 45), two humanities degrees (Comparative Literature min. 65, and History 63-74), or one in Computer Science (91-106) with a minor to spare.

These requirements were codified by the “Flexner Report,” an 846-page study of the state of medical education in the U.S. and Canada published in 1910 by physician Abraham Flexner through the Carnegie Foundation. Flexner’s response to the question of “how much education or intelligence it requires to establish a reasonable presumption of fitness to undertake the study of medicine under present circumstances” (23) was a “competent knowledge of chemistry, biology, and physics” (25).

In regards to chemistry, in particular, Harvard instructor in anatomy Frederick S. Hammett gave a speech to the American Chemistry Society in 1917 about the need to instill robust chemical knowledge in pre-medical students. “The true physician must be a true diagnostician. He can not [sic] be a diagnostician if he lacks power of observation and ability to carry on deductive reasoning. Where better can he gain this fundamental training than in chemistry?” Students are not supposed to be made chemists, per se, but they should be able to have the diagnostic capacity and attention to detail that intense training in chemistry provides.

Which sounds reasonable. But as Donald Barr, M.D., professor of pediatrics and Human Biology at Stanford, notes in his book “Questioning the Pre-Medical Paradigm,” these requirements were neither new nor scientifically determined. Regardless, it did have the effect of establishing the notion that “the extent to which a premedical student has succeeded in studying the sciences as an undergraduate is a reflection of the student’s inherent intellectual ability” and can gauge their future success as a physician.

Who leaves the track: Race and gender

Of course, we want doctors who know their science and medicine, who know how to think critically and analytically, who know how to work long hours under pressure. But do undergraduate science scores truly reflect a student’s capacity to be a good physician? In our interview, Barr described how science grades predict performance in the three national licensure examinations (USMLES) interspersed between med school and residency. According to Barr, “Your MCAT science scores and your undergraduate science grades predict your grades in the first two years of science classes in medical school, but not your clinical skills.” MCAT verbal scores and non-cognitive characteristics are better predictors of how well you do in ward rounds.

In addition, undergraduate science grades are inversely correlated with empathy scores. “For decades, medical schools have been using science grades to ‘weed out’ weak students when in fact, who they’re weeding out are the people with the best interpersonal skills, which are the best predictors of clinical skills down the road,” said Barr.

Barr was inspired to investigate pre-med attrition when he heard “I used to be pre-med, but…” coming more from women and racial or ethnic groups that are underrepresented in medicine (URM) among his sophomore and junior advisees. So he conducted a study following freshman who indicated an interest in pre-med upon entering Stanford. An average of 363 freshmen (~22% of the entering class) expressed an interest in pre-med. Of these, an average of 108 (~30%) were URM. Over the same time period, an average of 294 Stanford students applied to at least one medical school, 50 of whom were URM. He found that attrition disproportionately impacted URM and female pre-med students. Almost 50% of URM students dropped out of pre-med, compared to 17% of non-URM students. Another study surveying UC Berkeley students found similar results.

Many of these students cited chemistry as a deciding factor to drop out of the track. “Students hear that if you can’t do well in chemistry, you’re not going to get into medical school. And that was actually coming from the pre-med advising office,” said Barr. “Medical schools have historically used science grades as a marker of how qualified you are — and that’s problematic.”

But why is chemistry so notoriously the greatest drop-off point for pre-meds? And why does it disproportionately affect URM and female students?

Chemistry: The “weeding out” course

For many students, the word “chemistry” is synonymous with pre-med (and general frosh) misery.

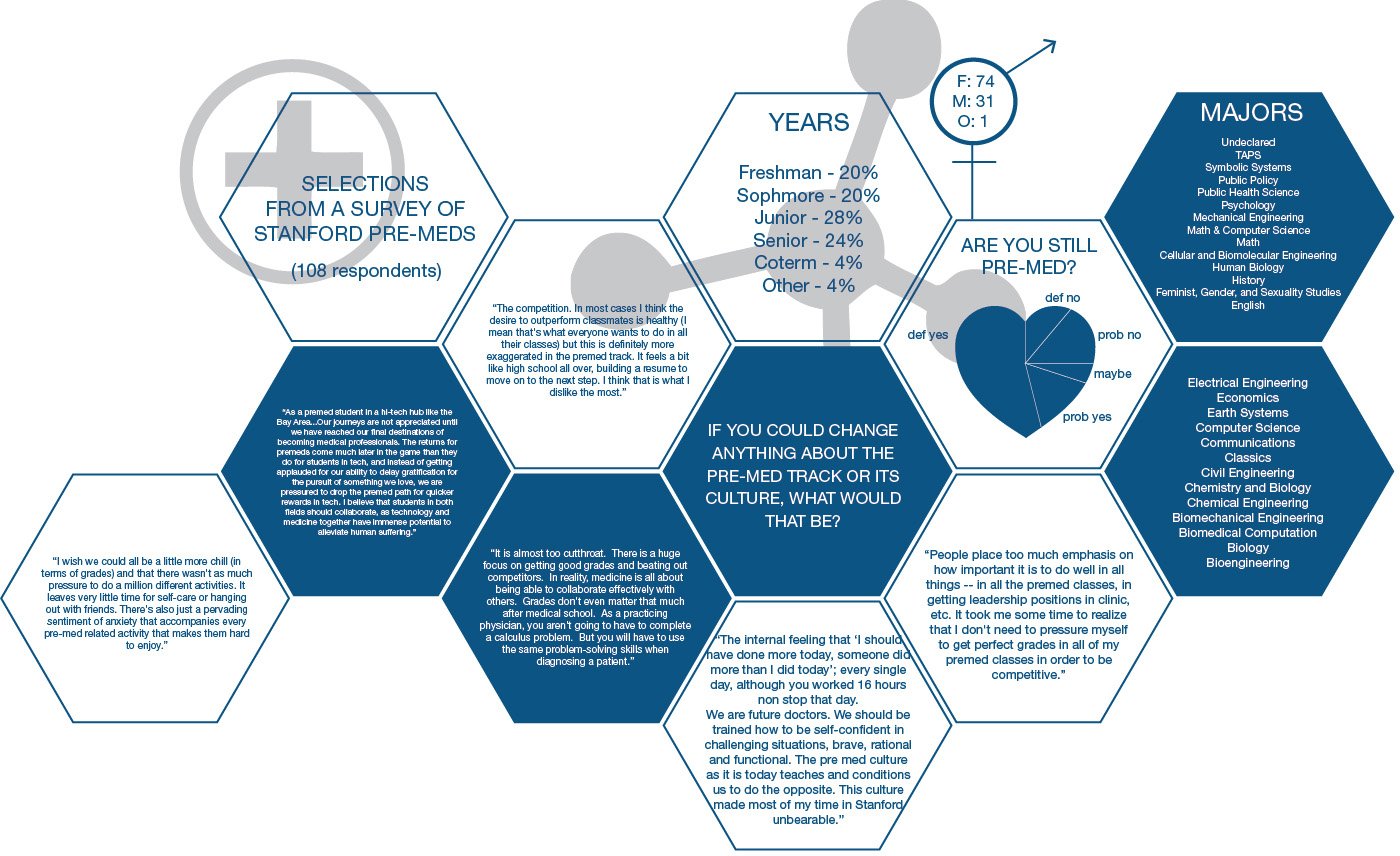

In a survey I sent to various email lists at Stanford to explore pre-med attrition, almost all 108 undergraduates and recent graduates cited dissatisfaction with the pre-med courses as the reason why they either considered or did drop out of the pre-med track. Of these students, the large majority explicitly cite the chemistry requirements as the main reason why they dropped out.

“Chemistry is important because it shows rigor,” said Skylar Cohen ’17, a senior co-terming in communications. “But if you put that in front of students without showing them the payoff, it’s an incredibly demoralizing environment.”

At the time of our interview, Anthony Milki ’17, a pre-med who wrote about his frustrations on being pre-med in the Stanford Arts Review, had just taken the Chem 141 final. “It really felt like I completely wasted my time studying. … like I could have not studied and done just as poorly,” said Milki. “I get that they want a grade distribution, but at what cost?”

Chemistry professors Charlie Cox, Ph.D., Justin Du Bois, Ph.D., and Jennifer Schwartz-Poehlmann, Ph.D., lecturers in the introductory chemistry series, are very aware that students consider their courses as something that “weeds out” pre-meds. “It’s so sad that we have legions of people who think chemistry is the worst subject they have ever studied,” said Du Bois. “We’re deeply committed to changing these attitudes, but these are hard and entrenched. … We’re really trying to get this broader community to see just how empowering understanding the language of chemistry can be.”

Contrary to the aura of failure that surrounds chemistry, they say, the numbers show otherwise. “What always confuses us when we hear this from students is that no one failed 141 last quarter, less than 2% fail in the general chemistry series, and most of those cases are due to a significant outside event beyond their control,” said Schwartz. “Our mission is to help people learn. There is no benefit to us to weeding people out.”

In addition, exams are “extremely well-vetted” and take at least 25 hours to make. “We run every exam between three to five TAs, and run it through the rigor before you even see it,” said Schwartz. Nor do the chemistry courses follow a true grading curve.

But if they aren’t “out to get you,” why does chemistry consistently evoke images of undue suffering, futility and tears?

One big reason is that chemistry is one of the first college-level science courses students take — and the transition can be hard. “If it were biology, there would probably be a lot of hard decisions made in there too,” said Schwartz. “The challenge is that compared to high school science, college is a very different ask of students. And it’s tough for people to change.”

“If you look at your average organic chemistry problem, it’s all about diagnosing the problem and ruling things out. That’s how medicine is practiced,” said Du Bois. “We try very hard to structure our classes and our problems to enforce this kind of problem-solving skill. But it’s not easy — most kids come out of high school and think science is about sticking numbers into an equation and getting a black and white answer.”

Cox makes a distinction between exercise and problems. “In high school we’re used to doing exercises in which the numbers are changed. You work problems over and over, learn the answer, and it becomes an exercise. You can’t memorize organic chemistry.”

They emphasize that there are many places to turn for help. “The department has collectively spent a ton of resources on service courses because we know that we’re servicing such a broad population,” said Schwartz. Office hours are run almost every day of the week, alongside extra review sessions, practice exams, online resources, VPTL tutoring and academic skills development.

For students coming in with little to no background in science, Schwartz and Cox jointly teach in the Leland Scholars Program, a summer transitional program designed to help incoming freshman who are first-generation or from under-resourced schools. “The program tries to look holistically at the student and address all the different challenges. We want to make sure that they get comfortable with the campus and the resources here. They take two exams in the [Braun] lecture hall here so they feel more acclimated when they walk in the first day.”

Schwartz also teaches the companion courses, “Problem Solving in Science,” that run parallel to Chem 31A/B and 33. Here, instructors teach study skills and group problem solving, ensuring that students practice chemistry from Monday through Friday. “It’s a partnership,” said Du Bois. “It’s about trying to encourage students to, like any language, practice a little bit every day.”

Compounding the diversity of student science background is the diversity of academic interests among students in introductory chemistry courses. “We’re actually a very service-oriented department,” said Du Bois. “The students we teach are not interested in majoring in the subject but need to have some kind of background and education in chemistry.” An average introductory chemistry course is populated not just by students in the life sciences but also in engineering, earth systems, English and, believe it or not, some students there just for fun. The problem that comes with that diversity is how to service everyone well when everyone has different needs.

The Chem 141/143 series “The Chemical Principles of Life” launched just this year in response to the disparity of student chemical and biological backgrounds in the biochemistry series Chem 171/181. “We were not really servicing the needs of the students as well as we could have because there was really a split in the population of the students in the class,” said Du Bois. In their third iteration of the series, they divided the class so students with strong chemistry backgrounds would go into a more chemistry-oriented 171/181, and students with strong biology backgrounds towards the cell biology-oriented 141/143.

They emphasize that they do listen and care about teaching and about their students. They don’t assign junior faculty to teach introductory chemistry courses, and they do frequent small group evaluations to modify courses in real time. “Just as your studying habits evolve, so do our teaching habits,” said Schwartz.

“I can’t tell you how much pleasure I get out of seeing a student who walks into Chem 35 knowing that it will be a horrific experience, and this is the class that will make or break their life in medicine. And by the end of the 10 weeks, they’re saying ‘This wasn’t so bad,’ or ‘That didn’t suck,’” said Du Bois.

“We’re passionate about chemistry and we’re enthusiastic about teaching chemistry,” said Cox. “That’s our ultimate goal.”

It’s clear that, though there are many resources available and changes are ever in the works, there are many students who are still struggling and slip through the cracks. Chemistry remains one of the biggest reasons why students drop out of pre-med. Until medical schools stop requiring chemistry prerequisites, students will need to not just study hard, but study well.

Skipping the requirements: Medical school by sophomore year

There is a workaround the pre-medical requirements, however. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s FlexMed Program is the first early admission program in the country. Students apply during the sophomore year, and with acceptance are “free to pursue [their] studies unencumbered by the traditional sciences requirements and the MCAT.” In fact, they explicitly state that students “will not be permitted to take the MCAT.”

Sounds like a dream come true, right?

David Muller, the dean for medical education at Mount Sinai, states that “FlexMed is all about flexibility in your education and the opportunity to pursue what you love to learn. It allows talented students with lots of initiative to ‘flex’ their intellectual, creative, humanistic, and scientific muscles during college.” Students are still required to take some of the traditional pre-med requirements before matriculation, though most are reduced by one semester to a year.

Natty Jumreornvong ’17, a senior in Human Biology and incoming FlexMed student, felt that pre-med requirements were “restrictive of [her] valuable time at Stanford.” She stumbled upon the program in searching for ways to free up space to pursue her interests and advance her career. “Honestly, I just Googled ‘medical school without organic chemistry’!” she said. “I was working on an electronic health records company at that time serving 5000 patients with chronic disabilities and spinal cord injuries in rural Thailand. I didn’t have the time or energy to be taking all the pre-med classes. I wanted to take classes that would be helpful for my venture.”

Jumreornvong also found FlexMed to be the best avenue into medical school for her as an international student. “I have a lot of friends who … are taking a gap year or two to finish up their pre-med requirements and take the MCAT. Taking gap years are unfortunately not the best option for international students who are here on a student visa. As an international student, pre-med advisors tried to steer me away from applying to medical schools because they said it is very competitive. Some undergrad websites were even upfront about it,” she said. “I feel like if I wasn’t accepted into FlexMed, I would have given up on pre-med.”

Donald and Vera Blinken, benefactors of the program, said,“Intellectual curiosity is as important as a stethoscope, and we’re pleased to support young people who are interested in the world and have broadened their horizons through the study of literature, history, and philosophy. It gives these students a real edge in their medical careers.” And for the most part, these students do just as well as their counterparts who took the traditional route. But why is such “intellectual curiosity” made available only when pre-medical requirements are taken out of the picture? If the humanities are supposed to provide a “real edge” to medical careers, why aren’t they requirements?

And what about everybody else?

The pre-med Marshmallow Test

There are many implicit hoops lining the way to medical school, couched in the maxim of “Do what you love the most and do it well!” Floating in the air are “suggested”checkboxes that include an A-average science and overall GPA (none of which may come from a community college), being in the 90th percentile in MCAT score, research experience, a running list of first-author publications, clinical volunteer experiences, extensive shadowing, leadership roles and three to five glowing letters of recommendation. Go to any “What are my chances?” section on an online pre-medical forum and you’ll see these components ranked, bargained over and passive-aggressively displayed like MMORPG stats.

In spite of all this, there is still the very real possibility of rejection from every med school you spent $160 plus $38/school (not including the $0-150 secondary fees, and the $310 MCAT registration fee — of note, the AAMC recommends that you “maintain strong credit as you begin the medical school application process”) to apply for.

There’s a lot of pressure to succeed — and for someone who has excelled enough to get into Stanford, stepping out of this endurance race feels like you’re either giving up or being lazy. But staying on pace often comes at the expense of opportunities for growth and development. “To do really well in these classes, you have to give up certain activities and attitudes that would make you a better physician down the line,” said Milki. “You have to probably not read books outside of class, where you learn from people who care. You have to give up being with your friends, though it’s important to have a support group.”

And often, the time and effort required to both stay afloat in pre-medical courses and not fall behind on your resume checklist can be all-consuming. Damien Sagastume ’17, who dropped pre-med to pursue teaching, was similarly frustrated by how pre-med stifles authentic passion and growth. “I feel like it’s a very prescriptive thing —they’ll tell you to be creative, but I feel like a lot of pre-meds do things because they feel like it’s what medical schools want to see,” he said.

Jason Li ’18, who took a break from pre-med his sophomore year, often found the requirements as a hindrance to his work in social justice. “The classes can feel really stifling for what I want to do,” he said. “They’re not necessarily the most relevant to what I want to pursue in community and public health … and they aren’t totally relevant to my major,” he said.

For Cohen, dropping out of pre-med gave him the mental space to more fully engage with his time at Stanford. “Not having to imagine med school admissions boards looking at my transcripts has made me enjoy Stanford rather than considering it as some brutal training ground,” he said

And for Gigi Nwagbo ’18, co-president of SWIM, she reconsiders being pre-med with every quarter. “I’m always thinking ‘Do I really want to do this’? ‘What’s my motivation’? ‘Why am I into this’?” she said. “Every pre-med class I have to take that’s a little extra and not required for [my major], that’s just taking up a lot of your time, that makes you skip out on your friends … You wonder why you’re doing it.”

As one survey respondent put it, pre-med necessitates a “suffer for the future” mentality, which is not necessarily a healthy habit. Nwagbo points to the allure of the faster, more lucrative pathways that surround us. “If you took CS, you get instant gratification,” said Nwagbo. “To be a surgeon, it will take at least ten more years of school.”

In a sense, being a pre-medical student is much like one big Marshmallow Test on steroids. But in spite of the long wait, and the doubts and setbacks that arise, many hold onto that end goal. “I question it every day,” said Nwagbo, “but you find your reasons.”

Stanford pre-med culture: Collaboration, fear, and a dash of anxiety

The stereotypical Pre-Med™ student, according to popular opinion, is someone who is mercenary in their extracurriculars and robotic in their emotional valence. They neurotically monitor their GPAs and are allergic to anything that won’t be on the test. They are “cutthroat,” in that they might very well literally cut the throats of their fellow cutthroat peers to have one less promising applicant to worry about. We hear stories about pre-meds who would give the wrong answers to someone asking for help, kick away another student’s dropped eraser during exams, sabotage another student’s lab results, or slash the tires of a commuting student so they wouldn’t skew the curve. These are just stories. But what makes these stories more horrifying is that we wouldn’t be surprised if they were actually true.

Luckily, based on the aforementioned survey and qualitative interviews, there is a general agreement that Stanford’s pre-med culture is not as cutthroat as other schools. In fact, there are many students who view Stanford’s pre-med culture to be collaborative. Nwagbo found that “people don’t see each other as competition — more as colleagues.” Michelle Chin ’17, co-president of SWIM with Nwagbo, has also found that the right peer support can make for a generally positive pre-med experience, even with the intensity. “We really care about our education because we want to be good doctors, but we support each other as well. And that’s something that I’m very grateful for. I made a lot of close friends from just doing p-sets and studying together.”

And there are a number of pre-medical student groups that aim to provide resources and support for students from a variety of backgrounds. These include SWIM, the Stanford Pre-Medical Association (SPA), the Stanford Pre-Medical Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association (APAMSA), Chicanos/Latinos in Health Education (CHE), the Stanford Black Pre-Medical Organization (SBPO), and Natives in Medicine (NIM), among other health and medicine-related groups. It helps to see people who are like you who face similar challenges as you all go forward.

But there is also a large contingent of students who feel that the pre-med culture at Stanford is far too competitive. Milki finds the pre-med environment toxic. “Stanford inherently breeds this competitive feeling that is really unhealthy,” he said. “It necessarily means I want other people to do badly so I can do well because of the curve, and it’s just really antithetical to how doctors should be. … I can’t help but feel like ‘I hope people bomb this test so I can do well.’ There is definitely a top-to-bottom system that forces you to be really scared. And when you’re scared, you’re irrational, and you start hating other people and being selfish.”

His experiences made him cognizant of an implicit hostility and self-destruction that the pre-med track can create for students. “I’ve just seen so many people crying after exams in chem. … There’s a degree of stress where you start to make bad decisions and doing things that are not good for yourself. A lot of these classes really breed that,” he said. “I’m not really getting much out of it. I’m not learning well or doing well. It’s frustrating to feel stupid — and it’s frustrating to have hard work not pay off.”

Of course, we care about grades. It’s very likely that many of us had no idea you could get something less than an “A” on your transcript. But in many respects, the pre-med gauntlet is a place where intellectual vitality atrophies. As one survey respondent put it, “I wish that pre-meds … would focus more on their actual passion towards their classes and studies, rather than being so grade- and outcome-focused. … I wish pre-meds would spend more time asking probing, interesting questions and not simply take the information at hand as fact. In a chemistry class, for example, I wish pre-meds would have more respect for another student who asks genuinely interesting questions, even if at the expense of review session time.”

Though pre-meds at Stanford might not outright sabotage each other, there is a running anxiety that begins from the first bad test grade in chemistry to med school admission results. And sometimes ambition begins to look hostile. The paradox is that while we all agree that we want well-rounded, mentally stable and compassionate doctors, the lengthy gauntlet of requirements does very little to support students in those capacities.

How many of those doctors have we lost in pre-med, in medical school, in residency?

The prestige factor

Most people who have an interest in going into medicine typically point to their desire to help people. In the aforementioned survey of 108 current Stanford undergraduate and recent graduates in 2017, almost all respondents cite a desire to provide service and care. Many cite a general interest in biology and science or being inspired and encouraged by a family member who is a physician. As one respondent put it, “It felt so admirable of a career to be able to spend my life directly impacting the livelihoods of others. The humanity of the role resonated with my aspirations to change the world for the better.”

But if we all we want is to be able to help other people, why not become a teacher, a social worker or a policymaker? Why not go into public health or work in some NGO or nonprofit or for-profit-for-social-good? Of all the ways that we can help other people and “change the world for the better,” why does it have to be a profession with one of the longest training requirements, the most grueling hours, the highest burnout rates, and the highest risk of death by suicide?

It could be that some people strongly desire direct patient interaction and care. But if that’s the case, then why not consider becoming a nurse practitioner or a physician’s assistant, where you’ll be able to do nearly just as much as the doctor with competitive pay, more face-to-face patient interaction, shorter training requirements, and greater leeway for a more hospitable lifestyle?

In the same survey, a little less than half had considered health professions outside of medicine. When asked why, the majority cite lower salary and social status and less prestige and authority. And this is what underlies the look of confusion that many a well-meaning professor, parent or mentor, among others, will give you once you tell them. And it often becomes a dirty little secret. Sarah Harris ’09, nurse practitioner student at UCSF, found little support among her peers and mentors. “When I talked to my advisor about it, he straight up told me it would be a waste of my Stanford education to do anything but medical school.” Then it becomes a game of justification — a desire “to help people” is not enough for these professions, regardless of the magnitudes of impact they might have over your average doctor.

Sagastume wrote about his decision to drop pre-med and pursue teaching in a Medium article called “Circular Dreams and Square Holes.” In the article, he contrasts telling his parents his decision to become a high school biology teacher to his experience of coming out — support vanishing in disbelief, and a hope that “This is probably just a phase.”

In our interview, he spoke about how he was inspired to go into education because of its long-term impact, and the mixed reception he received upon making that decision. “I was pre-med was because no one was going to second guess that. It’s a lucrative career that looks good on paper,” he said. “I’m a first-gen college student, and going to Stanford and being a doctor is like the next step up. … And to be a teacher, it’s like going a step down.”

His parents have since grown more accepting of his decision. But they still have their own notions of what is “the best” for their son. “I’m considering going to Harvard because they have a really good teacher education program. … And they’re all ‘You should go there!’ They’re still caught up in this idea of prestige. … It’s frustrating because they’re still looking for that. But they understood that this was the best decision for myself, as much as they wished I’d be a doctor and have financial security.”

It’s true that going to Stanford comes with the expectation of going on to do something that is either A) lucrative, B) prestigious, C) notable, or D) massively impactful, or a combination of the four. Careers that satisfy the above typically fall into the hallowed golden triad of doctor, engineer, lawyer (with the exception that you manage to land a page on Wikipedia, or get a spot in Forbes 30 Under 30 or TIME 100 — then anything is totally O.K.). Regardless of what we pursue, we must always be upward bound — to justify the sacrifices that were made to get here and to deserve the spot we earned in this rather fine institution.

We can’t deny that these “step-down” professions are valuable. We’d still want only the best teachers for our children, and the best nurses for our patients. It shouldn’t be considered a “noble” sacrifice or a cop out to choose to pursue careers that are just as meaningful and critical as being a doctor. And if the only reason why you’re going into medicine over some other profession is because of the prestige and the salary, what are you going to say in your interview?

The pre-med “canoe”

Unlike a number of other pre-professions that are freeform enough to give you the opportunity to explore, the seemingly rigid structure of the pre-med track often generates a deep-set anxiety about “falling behind” or falling off the train altogether and getting left behind in the bushes.

The track begins as soon as you check the box on your Stanford forms that you’re interested in medicine. You might be paired up with a pre-major advisor who has some form of experience in the medical field. If not, you’ll soon meet with a pre-med advisor who will give you a sheet of paper mapping out the rest of your four years. By the end of your first year, you should be on your way to at least the second half of the chemistry series, with several hours of clinical experience and a few leadership and research assistant positions in your pocket, a summer gig in healthcare, and, ideally, a budding spiritual romance with a faculty member you’ll ask to write a letter of recommendation three or four years down the line.

This is what’s recommended by the Stanford Pre-Medical Association’s pre-med timeline in their unofficial handbook, and suggested by Undergraduate Advising and Research, the AAMC, the Princeton Review, and most colleges. It may or may not sound like a lot; it certainly encourages you to be proactive.

But the problem of hopping on board so quickly, as we have seen, is quickly feeling like you’re scrambling, locked in, and unable to get out. Said one survey respondent, “It was difficult to take time to explore whether medicine is the right path for me because there were so many pre-med requirements that I felt if I did not take them right away, I would fall behind. As a result, I felt a little trapped and resentful.”

Barr suggests changing the metaphor — from pre-med “track” to pre-med “canoe.”

“The track will get you there — you just go straight. But,” he pointed to a map of the Central Valley. “Let’s say instead of boarding a train, you get on a canoe. You want to paddle up the San Joaquin River through the California Delta to get out to the bay. As we travel along the river, many watercourses diverge off into different paths. There are recreation areas we can stop by and eventually return back to our original pathway to the bay. The Delta has a rich network. Wouldn’t it be a shame to say I have to get out to the Bay as quickly as I can?”

“There are multiple flexible ways to prepare for medical school,” he said. “It’s not just if you can’t do the first two years of pre-med then forget it. … It’s up to you. Don’t think of it as there is only one way to get there. You choose the way that’s best for you.”

We hear about “non-traditional” pre-med pathways and know that they exist. But it means more than just majoring in something that doesn’t have “bio” somewhere in its name. A non-traditional path begins with an open mindset, where the opportunity to become a doctor need not start or end with undergrad and doesn’t necessarily involve a timeline or a checklist.

And this often makes for a more enriching time at Stanford. “In carving out my own path, and I’ve found a lot of support and mentors where I did not expect to,” said Li. “I’ve really come to appreciate what Stanford has to offer and how many doors it opened for me.”

Barr tells his advisees to change the question. “Don’t ask yourself if you want to be a pre-med — ask if you want to be a doctor. If the answer is yes, then go to med school.” Yes, you do have to make the grade. But graduating from Stanford should be telling enough. “The issue is not if are you smart enough to go to med school, but if you want to be a doctor. If you’re not sure if you want to be a doctor, there’s no point in going to med school. And if you’re not sure you want to go to med school, there’s no point in investing all your undergrad time in pre-med courses. Once you’re sure you’re sure you want to be a doctor, then get yourself ready for med school.”

There are people who took ten gap years who now work as doctors. There are extension programs and post-bacs, and ways to plan it out so you don’t end up broke. There are many ways to get to where you want to be, and there are people willing to support your journey there.

“There are multiple paths to becoming a doctor, and there is no one best path,” said Barr. “Each person has to find the path that fits them best.”

Improvements and changes

A little over a century after the Flexner Report, medical schools have heard, and they are starting to change.

Donald Barr points to a 2013 article in the New England Journal of Medicine on how the AAMC is shifting towards a more “holistic review” of medical school applicants. In one table, desirable physician traits such as “commitment to service,” “empathy,” “capacity for growth,” and “emotional resilience” are mapped onto application data elements like history of engagement with service, essays and letters of reference, adversities overcome and “distance traveled” in life experiences. “Intellectual ability,” shown in part by “academic record,” is just one of many components in a holistic applicant.

He also pointed out that the MCAT has changed from assessing “science recall” to “science competency.” It now has a section on the psychological and social foundations of behavior. And it focuses on the chemistry and physics relevant to biologic systems. As Barr notes, “Med schools are beginning to drop course requirements in lieu of demonstrated competency, leaving it more up to the students to figure out how to take the courses that will help them learn the material.” Stanford Medicine, for instance, “does not have specific course requirements, but a recommended preparation for the study of medicine.”

Of course, the way we teach introductory science courses and how we onboard students interested in pursuing medicine can be improved. “There are many types of changes [we can make],” said Barr. “Curricular changes, changes in how you evaluate applicants, but also changes in the mindset of students who are thinking about being doctors — so you don’t feel like if you got a C+ in a science course, that’s it for your chances of being a doctor.”

Barr points out Harvard’s two semester Life Sciences foundational courses, implemented in 2006. Courses are jointly taught by the chemistry and biology departments, designed to account for students’ different high school science backgrounds and enable students to take more focused pathways into science based on their personal interests.

Cohen suggests a survey course about the journey to becoming a doctor. “A lot of people decide to drop pre-med based on chemistry, which is not representative of the career,” he said. “I would much rather that Stanford offered some kind of course to give people a better sense of what pre-med or being a doctor was actually like, rather than students dropping out based on a chemistry course that has very little relation to what you’d actually be doing from day to day.”

Changes are being made. Though there isn’t yet data to see what impact they will have, we must continue to provide feedback and work towards a new paradigm of what is means to be a doctor, and who gets to become a doctor. And paramount to this effort are students themselves, and how they believe pre-med will serve them as they go forward to careers in medicine and elsewhere.

Going forward

But as changes are being made, what do we do in the meanwhile? Whether or not you decide to make a four- or 14- or 20-year plan, remember that you are capable. Remember to look for support outside of advising, and collaborate. Do not be daunted by classes, hold the sunk cost principle to heart, and don’t be afraid to drop out or stay in.

Pre-med dropouts and diehard pre-meds alike have some words of wisdom:

- Give it a shot — but don’t feel that you’re bound to it

- In fact, don’t commit to pre-med until your sophomore or junior year

- Spread the requirements out — don’t feel rushed about finishing everything

- Explore everything you can

- Immerse yourself in what a physician does day-to-day

- Remember there are innumerable equally (or more) impactful careers out there

- Things that feel useless can still be useful down the line

- Be passionate about things that need to be fixed

- Be passionate. Period.

- Don’t feel sad. Don’t feel pressured. Don’t feel scared.

- Go to office hours

We need doctors who are as diverse as the populations they serve. We need doctors who care about other people. We need doctors who read books and make art. We need doctors who believe in the art of medicine. We need doctors who are committed to social justice. We need doctors who are healthy, happy and unabashedly human.

We need you.

Contact Vivian Lam at vivlam25 ‘at’ stanford.edu.