For hundreds of graduating seniors each year, choosing to pursue a coterminal degree — a “coterm” — will grant them a year-long reprieve from the world outside the Stanford bubble. These students earn a master’s degree that they may work towards while completing their bachelor’s, easing the shift to graduate studies and the associated financial costs.

Yet the transition from undergraduate to graduate life is hardly seamless. Coterms who take an extra year at Stanford report taking on greater responsibility for all areas of their lives, from their courses of study to their housing. The social experience is also vastly different — while 97 percent of undergraduates live in on-campus housing that fuses their academic and residential lives, most coterms live off-campus in more independent and decentralized social environments.

Camille Townshend ’17 M.S. ’18 remarked that the maturity demanded by the coterm experience made the campus services she got used to as an undergraduate seem like “coddling” in comparison.

“It’s a completely different game,” Townshend said.

Reliving the admissions process

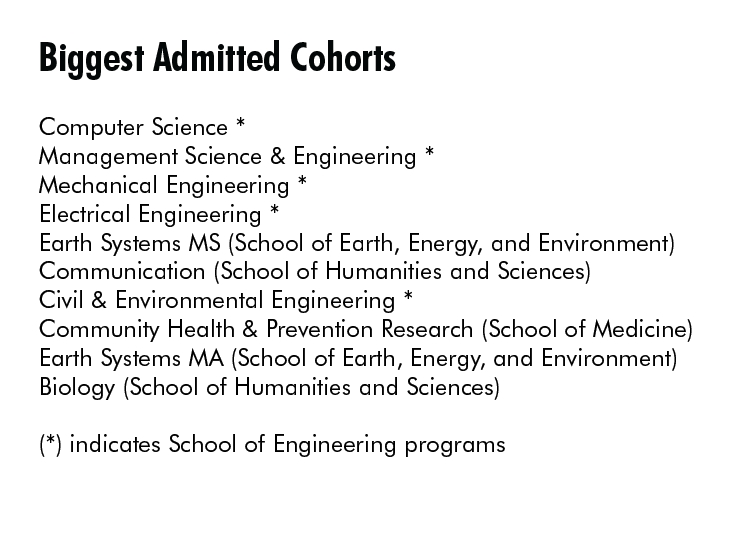

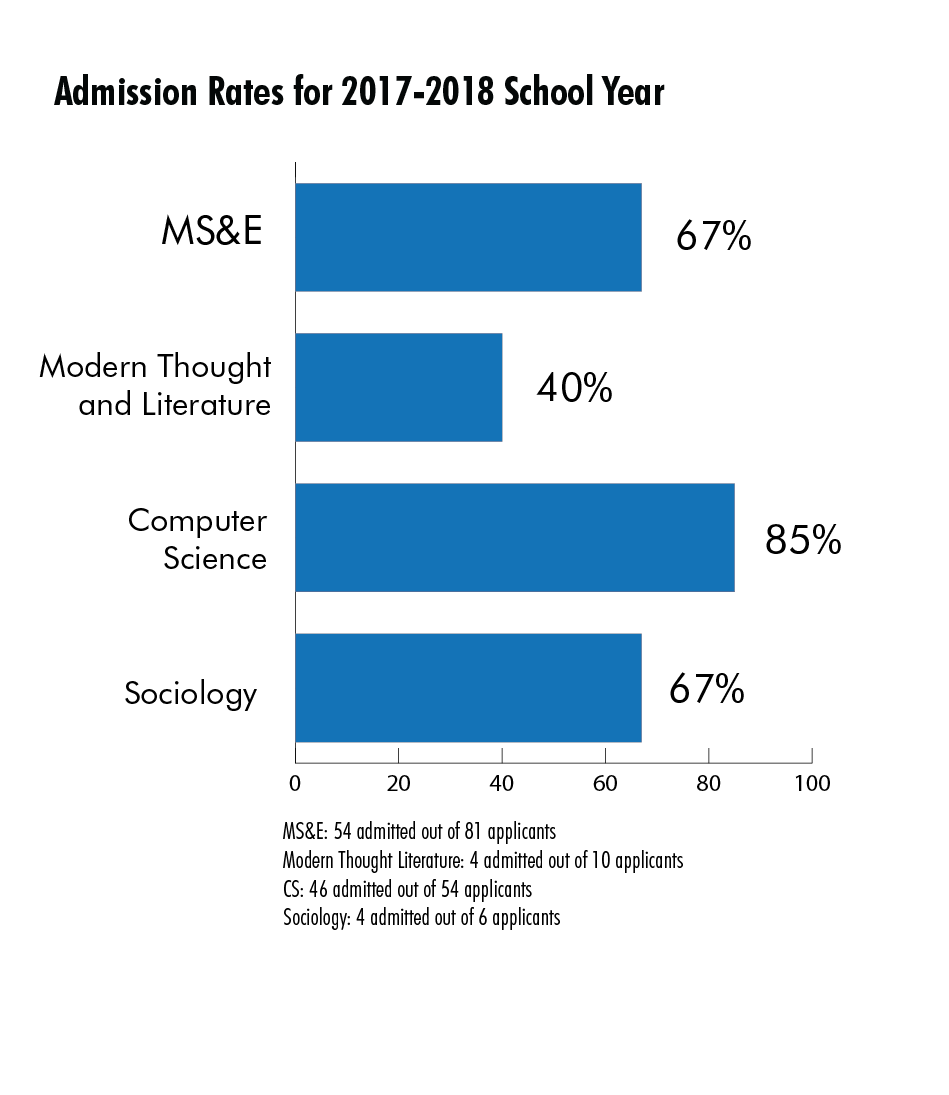

The differences begin with the admissions process itself. As undergraduates, Stanford students simply declare a major without an application form or GPA cutoffs. However, prospective coterms must apply to specific programs run by different departments, with admissions rates varying from around 40 percent for Modern Thought & Literature to 85 percent for Computer Science.

“For graduate school admissions, a narrow focus is preferred,” said Paula Aguilar, academic advisor and coordinator of coterminal advising with Undergraduate Advising and Research (UAR). “They want to see how you are prepared to be successful rather than looking at an applicant more holistically, as is the case for undergraduate admissions.”

Some programs such as Management Science & Engineering (MS&E) and Communications also pit Stanford undergraduates against a pool of external applicants, with students from other undergraduate institutions making up two-thirds of the current MS&E cohort.

Nor are the standards for admission the same for every program. According to Katrin Wheeler, student services manager in Communications, the program in media studies — one of two options in the Communications coterm — typically admits all students who find a faculty advisor before applying. Meanwhile, the computer science (CS) admissions process takes GPA in previous CS classes into consideration, alongside other criteria.

While coterm degrees can be attractive for the chance to develop skills in an area outside one’s undergraduate major — in the sociology department, for instance, 60 percent of the coterms came from different majors such as human biology, education and economics — students must often rely on research and networking to discover different programs.

Josh Lappen ’17 M.S. ’18, who is pursuing a master’s in the Civil & Environmental Engineering (CEE) department after finishing an undergraduate degree in classics, said that he only found out about his program through word-of-mouth.

“It’s key to know professors and talk to them — that’s the only way to find out about things,” Lappen said.

For certain programs, the application process may also be tougher for students in different undergraduate departments. As a physics major, Cody Kala ’17 M.S. ’18 had to apply again after an unsuccessful first attempt to gain admission to the CS coterm. Since he had only taken four computer science classes and had a narrower range of relevant experiences to draw on in his personal statement, he feared that his chances were slim.

“Since I had few connections to the CS department it was difficult to get letters of recommendations from CS professors,” Kala said. “Of the three letters I needed for the application, only one came from a CS professor.”

Aguilar, whose position as coterm advising coordinator was newly created in the 2016-2017 academic year, commented that UAR is seeking to centralize coterm advising.

“Coterms are still advised to seek help from their undergraduate department,” Aguilar said. “In the future, we’d like to view coterming more as an University effort to avoid any challenges coterms may face and also to create more programming.”

Money matters

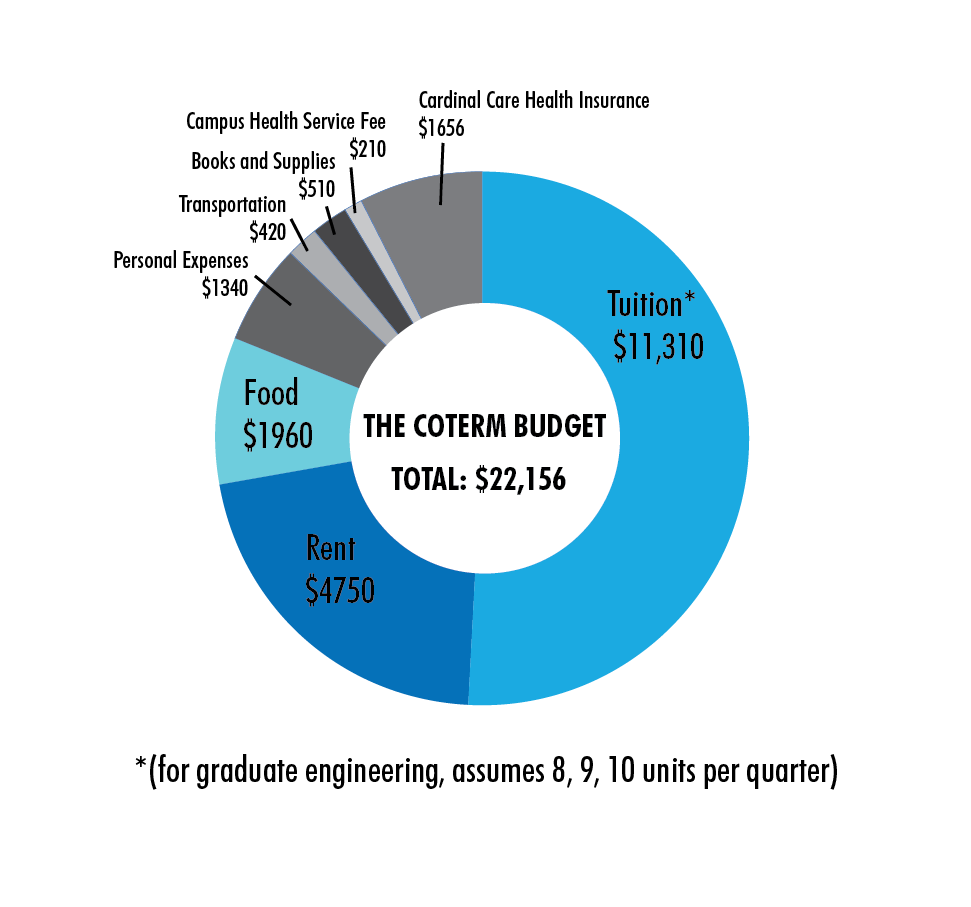

Once they find the right program, cost and convenience are powerful motivators for prospective coterms. Former Daily staffer Lily Zheng ’17 M.A. ’18, a psychology major and sociology coterm expected to graduate this year, said the fact that she could do a significant amount of coterm curriculum during her undergraduate career meant she only paid about $10,000 for an extra quarter to get a master’s degree in a different field.

Yet many coterm students still feel the financial strain of a master’s degree. While coterming at Stanford can be cheaper than switching to another institution for a master’s program, coterms face greater pressure to cover the costs of their education on their own than they did as undergraduates.

All U.S. undergraduates at Stanford receive need-based financial aid, but coterms are no longer eligible for the Stanford scholarship that supports undergraduates. If they require financial assistance, their only options are to take graduate student loans or to seek funding from their own departments — a difficult process since coterms are not eligible for most graduate grants and fellowships. Only a few departments offer aid programs that are open to coterms, such as the Engineering Coterminal Fellowship offered by the Dean of Engineering Office or the partial tuition support program for journalism M.A. students in Communications.

To finance their degrees, many coterm students seek teaching assistant (TA) and research assistant (RA) positions on top of their master’s program coursework. But the availability of TAships for coterms varies across departments — History, for instance, allows only Ph.D. students to hold TA positions that contribute to the cost of their education.

Aguilar noted that the absence of a consolidated list of all graduate assistantships is also a major obstacle for coterm students, especially since many of them seek two smaller assistantships across different departments.

Students who successfully obtain TA positions must also cope with the extra workload on top of their regular coursework. Danny Wright ’17 M.S. ’18 served as teaching assistant for CS 154 and CS 161 in separate quarters, with each course adding an average of 20 hours per week to his workload as a computer science coterm.

“I think it’s pretty worth it with interactions with students and seeing people’s process of learning and getting things,” Wright said. “It was worth it for me.”

For students who do not take up TAships or RAships, financial planning looms large. Zheng was careful not to enroll in any more classes beyond winter quarter to avoid paying more tuition fees. While the $10,000 cost of taking one extra quarter made coterming at Stanford cheaper than other master’s degrees she considered, she said that completing the coterm degree over more than one quarter would be “devastating” for her financially.

Kala, who had to take loans from the Financial Aid Office to pay for his coterm degree, was also struck by the change from the generous need-based packages he received as an undergraduate.

“From this point onwards I’m really on my own financially,” said Kala. “It’s a bit scary to think about, but now I look at it as taking my life into my own hands, and so at the time it also feels empowering.”

Housing crunch

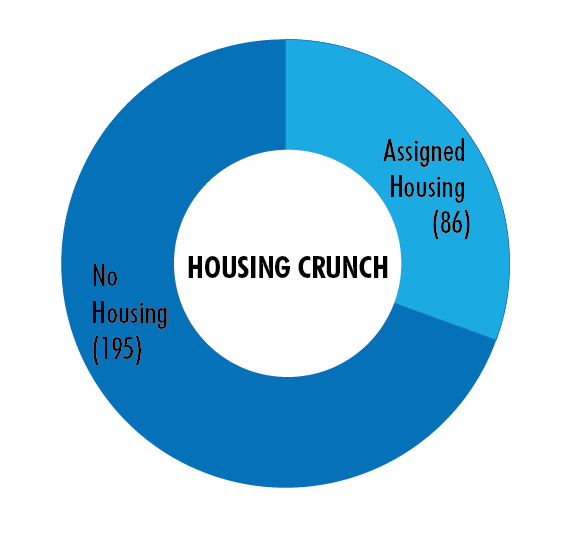

Another aspect of the transition to graduate life is physical: Coterms lose priority for on-campus housing after using their four-year undergraduate housing guarantee, which means that most of them must move off-campus.

As of Sept. 20, 86 coterm students staying beyond their fourth year were assigned housing in the 2017-2018 academic year out of 281 coterminal students who applied. Most coterm students seek off-campus housing as a result, whether with help from R&DE or on their own.

Once coterm students take a fifth year, they are considered returning graduate students. Since demand for campus student housing exceeds supply, R&DE assigns graduate students different levels of priority when they enter the housing draw — coterms are given low priority compared to external master’s students, graduate students and undergraduates who are not familiar with Stanford or its environs, especially since one third of graduate students are international and are not familiar with the U.S.

Townshend found the priority for coterm students reasonable given that other graduate students might be entirely new to the area.

“Coterms have been in this area for usually four years, so we’re probably the best people or the most adapted people to be put in this situation,” she said.

R&DE offers some off-campus housing in the draw, but coterms often choose to search for housing closer to campus than R&DE-owned housing — a process that can be especially tough for students.

According to Lappen, landlords in the Palo Alto area often preferred families who could sign multi-year leases and take better care of their living environments than the stereotypical student. In addition, the housing crunch in the area means that off-campus options are extremely competitive to begin with. The house that Townshend eventually found saw at least 20 other applicants, forcing her and her partner to strategize to persuade the landlord.

“We wrote them this love letter, talked about how responsible we were and all sorts of absurd things,” Townshend recalled. “[There were] lots of hoops and jumps you went through to get a decent place near campus.”

While the R&DE-sponsored Community Housing office also offers a Stanford affiliates-only rental listing service in partnership with Places4Students — a service publicized on R&DE webpages and its graduate housing brochure, which is circulated to students via email — both Townshend and Lappen said they did not know about the listing service and relied on their own research throughout the process.

Despite the challenges, students welcomed the process of securing housing and taking charge of day-to-day chores with their housemates as a step towards independence.

“That’s fine, and that’s what the rest of life is like,” Lappen said.

Leaving the nest

For many coterms, living off campus after most of their graduating class has left altogether radically alters the social experience.

“It’s just a difference of scale — by senior year you just know so many people that the act of being on campus is very familiar,” Lappen said. “[My coterm year] will probably feel a little more like freshman year in that way just because there are so many fewer people I know on a day-to-day basis.”

Greater independence and detachment from campus social activities have proven refreshing for some students. Amy King ’16 M.S. ’17 said that her choice to live off-campus in her coterm year allowed her to separate academic life from residential life, a sharp contrast from her undergraduate years.

“Moving off campus and living a few blocks away inherently makes campus feel more like school and less like a home,” King said. “The urgency to be involved in every event also diminishes, so I ended up spending my free time with more intention and travelling more on the weekends.”

Living independently also means more time spent on domestic tasks in addition to schoolwork and student activities — a pleasant novelty for some.

“We’ve spent this past week hunting for furniture and assembling stuff,” Lappen said. “It’s been a lot of fun.”

But for other students, the transition from the undergraduate community to graduate student life still evokes the occasional sense of nostalgia. Katie Bick ’16 M.S ’17, who chose to live off-campus to prevent her coterm year from feeling like an “extended senior year,” felt the difference keenly.

“Every time I biked past East Campus, I felt sad and nostalgic,” Bick said.

Some coterms also believed that living apart from other graduate students in their department made it difficult to build academic community, detracting from their experience as students.

“Part of why I’m excited to do a master’s is to meet all of those people coming to Stanford who haven’t been there before,” Townshend said. “It’s isolating and alienating to not be able to live in the same space as those people.”

Townshend said that the events organized by her department — Mechanical Engineering — are mainly informational or academic sessions that do not encourage casual socializing.

Size also makes a difference when it comes to a sense of community. Zheng said the fact that there were only two or three other coterms in the Sociology program, coupled with a lack of social events, made for a lonely academic experience.

“Coterms don’t really socialize with each other, so it seems that we are completing a degree by ourselves,” Zheng said. “There is not much community support.”

Some students in other departments were able to build community around their academic goals, albeit to a limited degree. Bick appreciated that her fellow coterms as well as external graduate students in the Community Health and Prevention Research program bonded through student-initiated group study sessions. Like many of her fellow coterms, living off-campus prevented Bick from staying to socialize for long, but she said her cohort “felt way more of a community than [she] thought it would.”

Student groups, new housemates and mutual friends also help coterms to rebuild their social experience after their undergraduate communities disperse. Bick fondly recalled a student-organized coterm election party she attended during the 2016 presidential elections, but she laughed at the idea of attending undergraduate all-campus parties.

As with finances and housing, coterm students reported taking more responsibility for their personal relationships than they did as undergraduates. Andrew Lee ’17 M.S. ’18 said he thinks that coterm students make the social transition to life after graduation more easily than students who must start afresh in a new city — provided that they take the initiative to build and maintain friendships.

“Luckily as a coterm here you already have established roots here, so it’s not as difficult to have social engagement but it takes a lot more effort,” Lee said.

On balance, coterm students said they felt less reliant on the University’s resources and less connected to the campus community than undergraduates.

“When you’re getting your bachelor’s, you’re here for the experience; as a coterm it really feels like I’m just getting a degree,” said Zheng, who works a nine-to-five job in addition to her studies.

But the degree aside, the rest of their time is in their hands — a prospect that can be exhilarating.

Fangzhou Liu contributed reporting to this article.

Contact Fan Liu at fliu6 ‘at’ stanford.edu.