It’s October, and “Frankenstein” is in the air. Not quite literally (though I did throw my book up in celebration upon finishing it just in time for section), but as the 200th year anniversary of the book’s 1818 publication approaches, people are talking about the classic horror story. Truly novel at its time, “Frankenstein” was written by a woman and raised all kinds of questions about romanticism, gender, creation, the pursuit of knowledge and the limitations of our creativity, especially in the form of the novel and the horror genre. These themes translate nicely into our own time, particularly in relation to artificial intelligence and biomedical ethics.

And these are all topics worthy of attention, but this weekend, Frankenstein’s got me thinking about a different thing. My favorite thing, really: me. Bear with me here, because I think it also has something to do with home and Stanford and maybe even you.

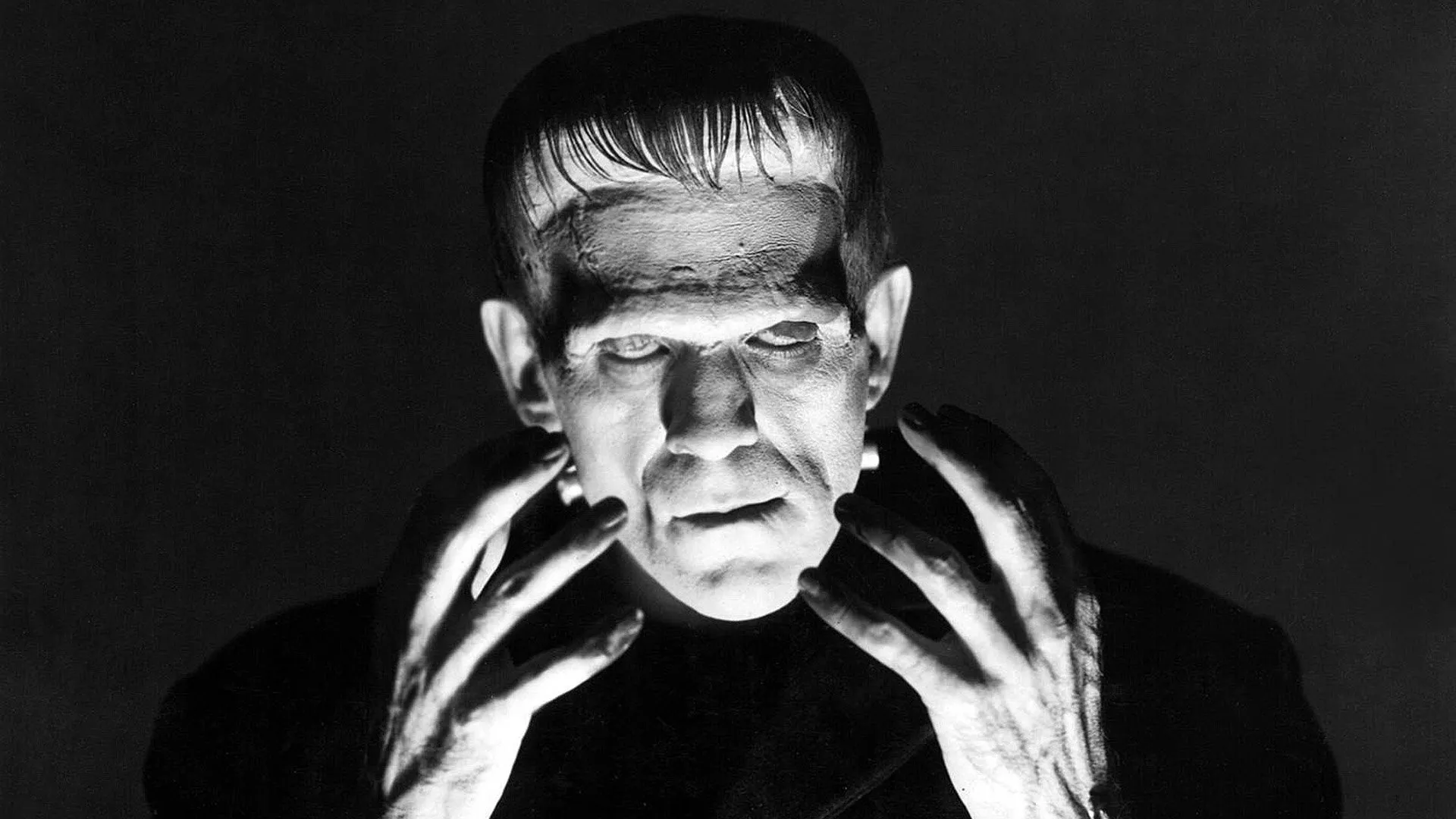

Before getting all presumptuous, let’s return to our friendly neighborhood monster, who is pieced together by his creator, Dr. Frankenstein, in an imaginative fervor. The doctor recalls, “His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful!” But what does he get from these nice little parts? A being with “watery eyes” and “shriveled complexion and straight black lips.” A disproportionate and monstrous-looking thing, a thing often referred to as Frankenstein. This brings us to one of the biggest misconceptions about this story: that the ugly, nasty, people-eating monster is named Frankenstein. Really, Dr. Frankenstein is the monster’s creator, and the monster himself remains unnamed.

Another misconception is that this nameless creation is simply an ugly, nasty, people-eating monster. Yes, according to Shelley, he does “grasp [a child’s] throat to silence him, and in a moment he lay dead at [the monster’s] feet,” which, even though it’s not people-eating, is pretty nasty and, in the end, any act of murder is difficult to justify. But the part that people forget is what comes just after: The monster says to Dr. Frankenstein, “I am malicious because I am miserable. Am I not shunned and hated by all mankind? You, my creator, would tear me to pieces and triumph; remember that, and tell me why I should pity man more than he pities me?” Which raises the classic question: Is Frankenstein’s monster a monster at heart? What’s more: What would have happened had Frankenstein been gentle to his creation? The popular conception of Frankenstein has often ignored these questions in favor of the simple throat-wringing. And really, I can’t blame them; it’s less fun to think about the nuances of the human condition in the face of a really good murder scene.

But maybe this false conflation is actually helpful. If we think of the monster as a part of Frankenstein, and think of ourselves as a Frankenstein of sorts (I know, a lot of thinking), the relationship between monster and creator becomes a sort of embodiment of self-fashioning.

Frankenstein goes into the process with all these pretty pieces, like little points on an Excel spreadsheet, and when he doesn’t get the pretty thing he expected, he “screams like a tiny child and runs away, the wimp.” (Okay, that’s not the real quote, but you get the gist.) Afterward, the monster goes on to have a life of his own, independent of Frankenstein’s influence. He even ends up giving himself a classical education after stumbling upon a random suitcase full of canonical works (convenient, M. Shelley). A happy coincidence, not unlike stumbling into a Great Books program freshman year …

Despite being Frankenstein’s creation, the monster ends up making himself. What’s more, he becomes a pretty well-educated dude, and also (at least in the beginning) a peaceful one. He is not what Frankenstein expected, but he’s really not that different from Frankenstein himself.

But, you ask, how does this act of creation in the 1800s relate to me? Well, other than that truly monstrous haircut of my junior year, I have – at various points in my Stanford tenure – felt a bit like Dr. Frankenstein. There is a sense that somehow, I am going Somewhere, a definite place, a Home, a Self, and that if I piece together little experiences and classes with an eye to those shimmering ideas, somehow, at the end of my four years, a coherent person with a unified home will emerge.

That’s at least how I felt coming out of freshman year, still rather lost, but thinking that declaring a major (maybe even a minor!), having an established friend group and an Excel Spreadsheet labeled “Academic Plan” might make me feel more on track.

A dropped classics minor and a haircut or two later, I am dangerously close to the end of my time here, and I’m back to feeling like Frankenstein; nothing coherent has emerged. My freshman friend group has dispersed around campus; I’ve ended up in a co-op I mistook for a fraternity my freshman year; I have friends on the ultimate frisbee team (which, in fact, is indeed a sport), and I realized that, despite utter eagerness, I can’t take more than two English classes at a time.

Frankenstein’s creation doesn’t come out looking like the sum of all its parts. Instead, it is something bigger and uglier, something far less understandable and underneath, I suspect, still quite human.

2018 marks the anniversary of Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, and my final year at Stanford. Some interpretations say the novel is a warning about overreaching our human capacities, about trying to create something whole from an assemblage of parts. But I think that this process is perhaps the heart of self-fashioning. Rather than a warning, I think there’s something else there, something about trying the best we can to make ourselves (planning out those classes, trying to run the Dish, maybe even going to a job fair or two), and then accepting the strange disproportionate thing that we get – the imperfect human, or the unexpected home.

Contact Emma Heath at ebheath ‘at’ stanford.edu.