When Rupi Kaur’s second book “The Sun and Her Flowers” was released, my friend asked me what my thoughts were about the work. I hadn’t read it with the intention of never doing so, and when I told her this she wondered why. It was a #1 “New York Times” bestseller, after all, and Kaur is now known as one of the most famous poets of our generation. What was there not to like?

In actuality, I was a bit of a hypocrite for saying I never intended to read the work. I had actually gone to the bookstore the day the book was released and bought it immediately. It sat on my desk, unmarred, pristine with its cream-colored cover and genteel illustrations for two weeks. I do not know why I hesitated so. Maybe it was because it was a bestseller and I did not want to be part of the crowd. Maybe it was jealousy that someone so young could succeed so fast, a future I wish I could attain but know is nearly impossible to achieve. Or maybe it was because I was angry at it, frustrated at what the book marketed itself as: a book of poems. Because in doing so, in labeling itself as poetry, I thought the book was falsely advertising its style.

I will focus on one “poem” that Kaur has in her book to try and provide evidence for this harsh critique. In her “poem,” “growth is a process,” Kaur writes this: “you do not just wake up and become the butterfly”.

That is it. That is the whole poem. No line breaks. One sentence. It is simple and conveys a clear message, and its message can be universally relatable. The line has a metaphor, so it fulfills the figurative language checkbox of poetry. How is it not a poem?

When the same friend I mentioned earlier ended the conversation with this question, she gave me an example of William Carlos Williams’ poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” as a counterpoint to my criticisms. The poem goes as such:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

It does much of the same things as Kaur’s one-line poem does: it has a title, is all in lowercase letters, is technically one sentence, and uses colloquial language that is easy to understand. The only difference, visually, is line breaks. So, my friend’s question was valid. Why did I consider Williams’ work a poem and not Kaur’s?

I ruminated on this for a while, and my answer is this: poetry always leaves a question for the reader to answer. What drew me into poetry and into English as a major was not its symbolism or its line breaks, but its continuous push for me to ask questions about language, the emotions it instills and the story it unveils. A poem is a constant game of uncovering, of opening a new layer to something that feels illegible and inaccessible, only to open unfurl, line by line, to leave us with questioning or understanding an aspect of life we may not have understood before. In “The Red Wheelbarrow” we are left with a multitude of questions. What is the importance of the wheelbarrow? Why are the chickens there? Why rain water? And with these come more metaphysical ruminations: Why focus on such menial things? Why do objects hold so much importance? What does it mean to be dependent on something? The writer never intends to give us the answer but places us in a situation where we are eager to solve it. We become intellectually curious, asking for more. We become hungry for language, ravenous for thoughts. And isn’t that beautiful? Isn’t that poetic?

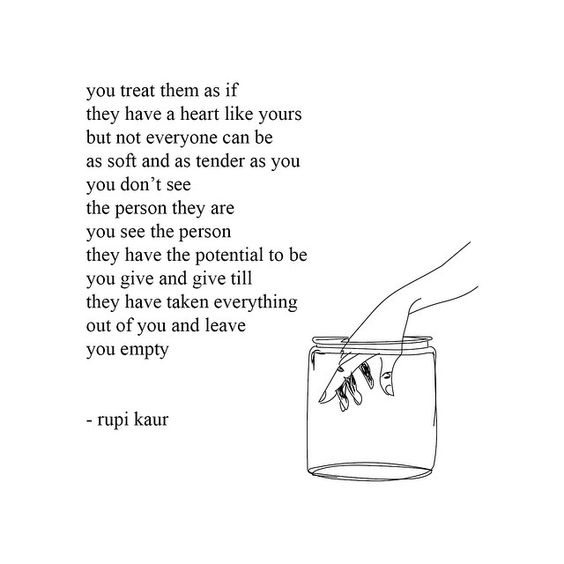

Kaur’s work provided all of the answers for us: her intentions were clear, her issues clarified, her answers determined. I felt like I was reading a universal manifesto, a relatable diary, a set of rules and realizations and epiphanies. There was never a moment when I needed to ask a question, and it was due to this lack of unknowing that I was left feeling like Kaur was distorting the functions of poetry by promoting her work as one.

What brings me the most anguish from this book is that the majority of people enjoy it, relate to it, feel that — finally — they understand poetry, which to many seems just like a figurative language gumbo. Most see Kaur’s work as an introduction into the world of poetry. Yet, if I follow the crowd, if I accept Kaur’s work as a collection of poem, I feel as if I am betraying my own craft, my own creative writing concentration that I seek to study for the rest of my life. Because, to be frank, poetry is not like this. It takes time. It takes work. It takes an emotional toll. It requires unanswerable questions and ruminations that haunt. Poetry should not feel like an easy read but an intellectual and emotional journey, one that has checkpoints, setbacks, riddles. Poetry, through its line breaks and symbols and rhymes, enables us to stretch language to its fullest capacity, to let it enter into realms unfathomable and strange and, ultimately, beautiful. It would be a shame to have people’s first impressions of poetry be one in which the answers are already right in front of them, and they never get to play the wondrous game of language within the poetic realm.

Contact Sun Paik at spaik97 ‘at’ stanford.edu.