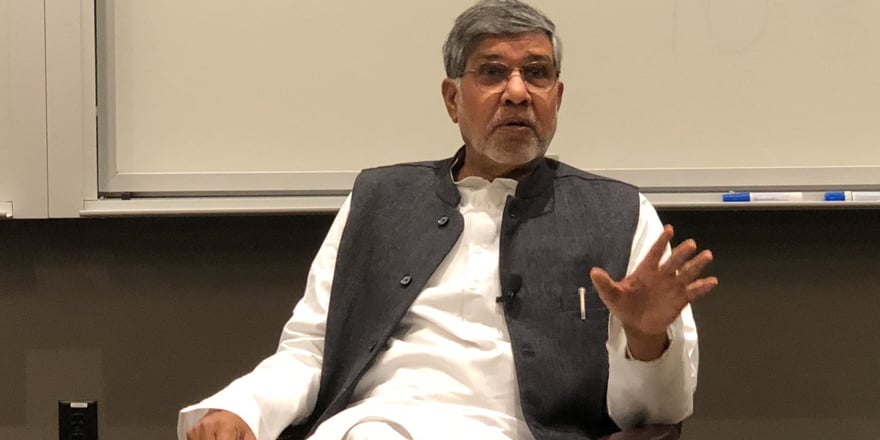

Kailash Satyarthi is an Indian children’s rights activist and the recipient of the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize. He founded numerous organizations including Bachpan Bachao Andolan, the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, Global March Against Child Labour and GoodWeave International. Through these organizations and other efforts, he has rescued over 86,000 children in India from child labor, trafficking and slavery. The Daily sat down with Satyarthi to learn more about the inspiration for his work and his take on future world challenges.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): Many people around the world consider you a role model. Who is your personal role model, and why?

Kailash Satyarthi (KS): Frankly speaking, my role models are some of those children whom I rescue. I see the unlimited power and the infinite energy inside of them, along with the zeal to restore back their childhood and freedom. That gives me tremendous inspiration. But I am definitely influenced by some of the great people, like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela. They were definitely my inspirations in childhood, and even now.

TSD: How does having children of your own influence the work that you do?

KS: I engaged my family right from the start. My wife, for instance, has always been an activist and she has been leading many activities, particularly the rehabilitation and education of freed child slaves. She’s in charge of many rehabilitation centers. My children were born and grew up in difficult situations where they were threatened – my office was attacked, I was attacked several times and my son was attacked. They grew up in that environment, so they understood the gravity of the problem.

My son is one of the top lawyers on child rights and human rights in the country, and most of the judicial policies drawn up in the last five or six years are due to his efforts in India, so he’s part of an organization leading activist efforts. My daughter was also very involved when she was a child, but she was under serious threat, so my colleagues and some friends in the U.S. insisted on bringing her here. My children were engaged in my work from the start.

TSD: What exactly do you find so inspiring about the young people of this world?

KS: The youth are full of energy and enthusiasm, but they also have a strong element of idealism and optimism that is rarely found in elderly, wise people who think twice, thrice or four times about taking risks. The youth take risks, and that is a great wealth that can be generalized for a better cause and for a better objective in life. Many young people are looking for a better purpose in life, so if we are able to give them a better purpose, then we are engaging them in some worldwide movement. Young people also look for some scale; they don’t want to do smaller things — they want to make a big difference. That is the most inspirational part: how their energy and enthusiasm and idealism can be converted into [a] social movement.

TSD: Given that you hope these young people will change the future one day, what are some obstacles you foresee for them?

KS: There is still a big fight against the growing inequality in the world. I always say that inequality is an economic violence, and we are facing this violence and it is growing. In my opinion, that is still a big challenge. The bigger challenges are the unemployment crisis and the problem of refugee children, which we are still not able to properly address. So many children are moved, including those who were uprooted from their native villages due to natural disasters or global warming or scarcity of water, forcing families to run. This means that children are forced to leave their schooling. The economic crisis in a number of countries means they cannot solve this problem, so we have to look for alternate ways to mobilize resources for health and education and the safety of those who are displaced or seeking refuge in other countries.

TSD: Can you describe your idea of a perfect day?

KS: A perfect day would be one where every child is in school. They’re enjoying fighting with each other, being naughty, enjoying childhood to the fullest — jumping, questioning, questioning society, questioning cultures, questioning religions, questioning politics. That childhood is needed, and one day it is going to happen.

To learn more about Satyarthi and his humanitarian work, visit www.100million.org and www.satyarthi.org.

Contact Veronica Kim at vkim70 ‘at’ stanford.edu.