“Undergraduate Research: Resources and opportunities abound at Stanford, giving you the chance to turn the questions that kept you up last night into the way the world will live and think tomorrow.” Posted on the admissions site, this is the perfect statement to appeal to the Stanford-esque desire to positively impact the world before turning 30 years old. But in reality, how accessible are the research opportunities and resources this statement alludes to?

In spite of the increasing amount of publicity around programs like Bio-X, VPUE fellowships, and UAR grants for summer research funding, the first step of finding an actual lab to do research in is often the most difficult part. As an inexperienced undergraduate figuring out what to major in, I felt like approaching such accomplished professors about lab positions would be frowned upon. That was, until I joined my current lab in the Med School.

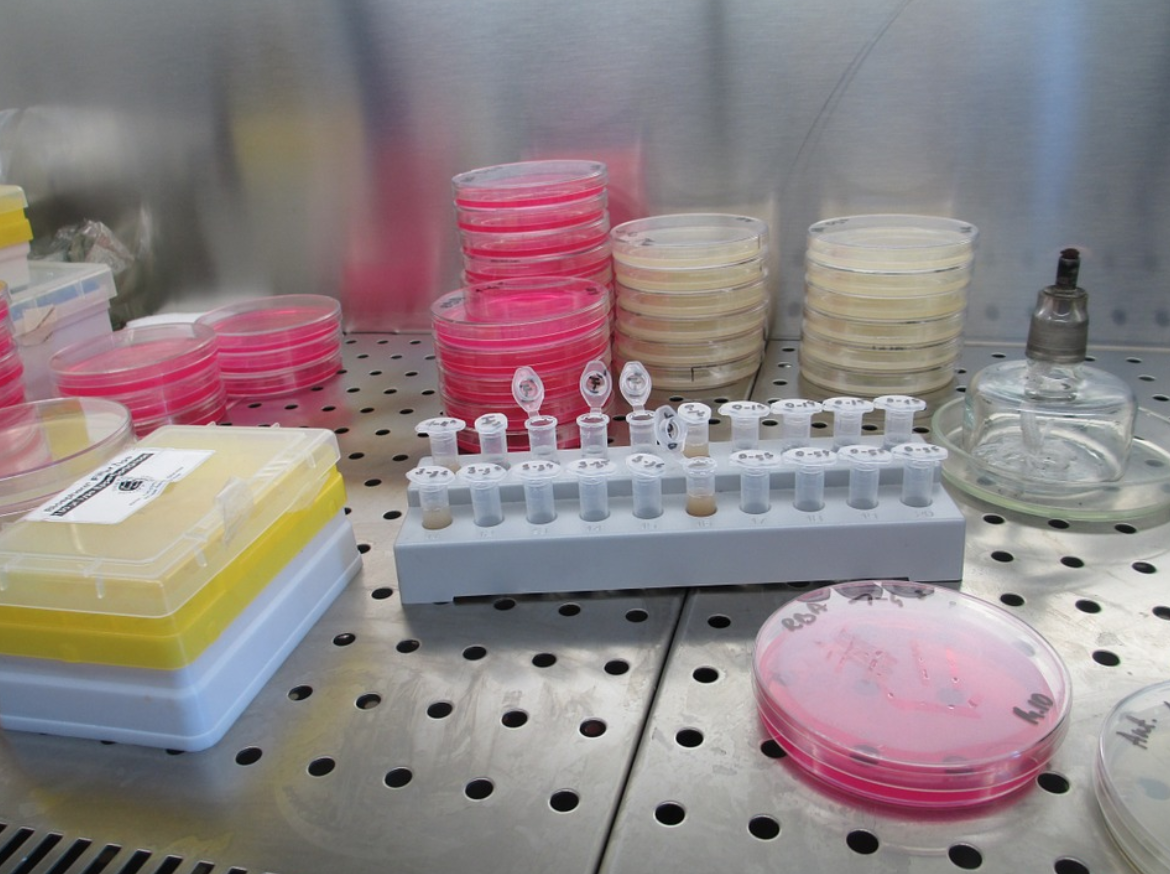

My background in science consists of one year of iffy chemistry and one year of slightly questionable biology supplemented by a mere six weeks studying stem cells. Wanting more exposure to structured research, I inquired during fall quarter about a position for a lab that was using planarian worms to model cancer development. Though I knew I found this area of research fascinating, I had zero idea of what a planarian even was or the basic biology behind cancer. Yet, thanks to an email, an informal interview and guidance from my amazing lab mates, I now understand more about the experimental process than I ever did in the classroom.

As an undergraduate with sparse experience and limited time to dedicate to my lab, I definitely don’t think that my research contributions will change “the way the world will live and think tomorrow” anytime soon. In fact, it’s already two quarters in, but I still only fully trust myself with the basic cleaning, amputating and sometimes feeding (if I’m feeling extra confident) of our test subjects. However, it is true that I am drawn to research because it makes me feel like I’m contributing meaningful work that benefits someone other and something bigger than myself — a satisfaction that I don’t necessarily always get from my classes. Furthermore, I believe that lab skills are helpful to cultivate for your personal benefit whether or not you pursue academia. Being in a lab encourages you to push yourself to be creative and innovative when designing experiments; it pushes you to be original. And when you do come up with that perfect experiment, you have to learn how to adapt quickly, trouble-shoot effectively and be persistent because there will be inevitable problems. Above all, you are forced to genuinely appreciate even the negative tests results because you quickly learn that they will be extremely helpful in some unpredictable way later on. Lastly, you learn to concisely summarize and communicate your findings whether that’s in the form of a presentation or a paper. Research offers so many learning and skill development opportunities that often don’t cross people’s minds. So, if you do feel yourself gravitating towards research in any subject, go for it — it’s an experience that can never be deemed useless.

Speaking from personal experience and from what I’ve gathered from my peers, email will be your best friend when it comes to finding the ideal lab for you. Through google or joining mailing lists, find a few professors whose work interests you and email them. Express why you want to contribute to the lab, mention specifics about their prior work, be concise and be respectful. It may seem daunting at first, but at the end of the day professors are human too — what’s the worse that can happen? If it is rejection you are worried about, think about the extensive number of labs on campus and the anonymity email communication gives you. No one is tallying the number of labs you are reaching out to, nor the number of labs turning you away except you. If you are questioning whether you are “good” enough for the high quality of Stanford University research, don’t; take my lack of prior experience as an example.

Contact Serena Soh at sjsoh ‘at’ stanford.edu.