Using CARTA to plan class schedules lowers students’ grade point average (GPA), according to a paper published by a group of Stanford professors.

Researchers divided students into two random groups. One group was encouraged to use CARTA by an email from Stanford’s registrar and a prompt in the University’s course enrollment system. The control group received no encouragement. “We found that platform usage caused a significant reduction in GPA during the subsequent academic term,” the study concluded, citing the feature that allows users to see previous grade distributions in courses they plan to take.

The researchers noted an average GPA decline of 0.16 standard deviations for students using CARTA. That translated to a 0.28 standard deviation decline for freshmen and sophomores, but only a 0.09 standard deviation slide for juniors and seniors.

Reduced course flexibility could counteract the motivation problems the research found stemming from site use, as packed schedules offer few chances to slack off in leniently graded classes.

The study also concluded that students do not necessarily change their course selection due to information from CARTA; only grades are affected.

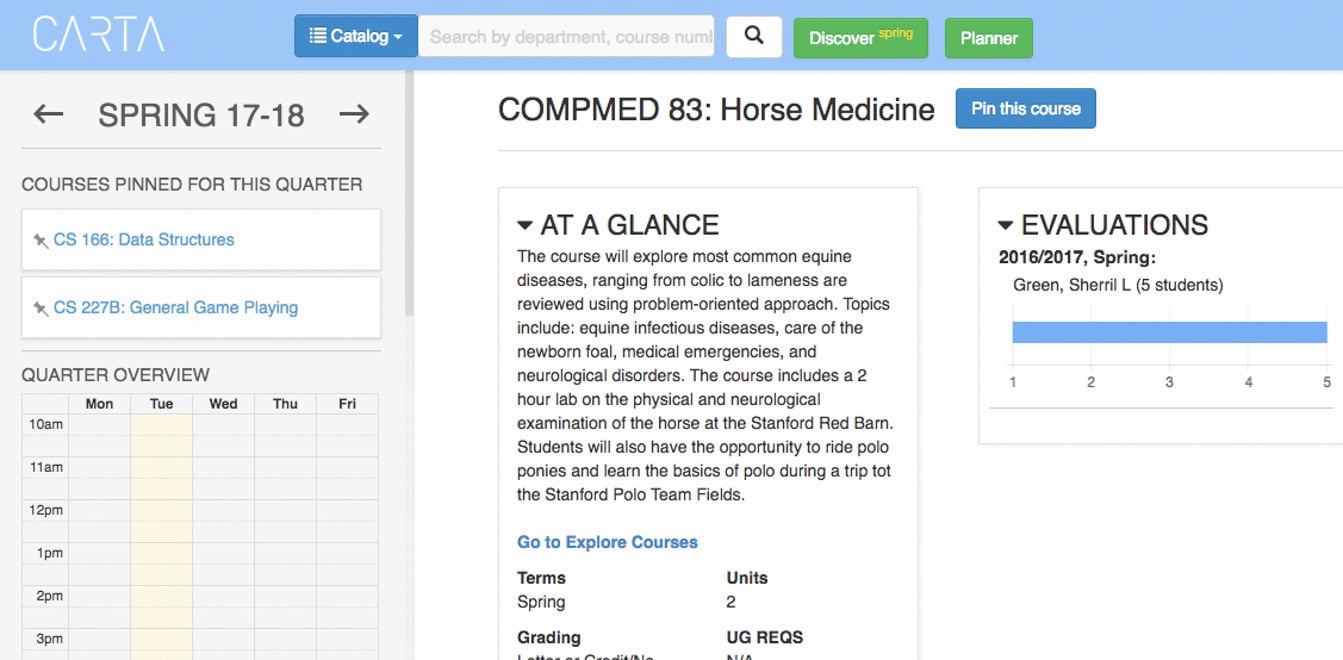

Within CARTA, it was the historic grade information that negatively affected students’ GPA.

“Those who saw grade distributions on CARTA had slightly lower GPA’s than others,” said Graduate School of Education Professor Mitchell Stevens.

The information CARTA has on course workload, meanwhile, was not found to harm students’ GPA. Indeed, for students who viewed the intensity card “there’s some evidence that the influence went in the other way,” Stevens said.

The experiment collected data on students’ usage of CARTA. While no data was restricted from students, some information was automatically collapsed and thus not viewable unless clicked on. Researchers could tell what information a student accessed by reviewing which windows remained hidden and which were actively selected for viewing. A student whose CARTA page automatically displayed grade information, but who never clicked to view the intensity card, would be classified as only using grade information to review that course.

The landing page of CARTA states that the website is a research project.

“It’s a research project as well as a service, but we really value the trust of the users so we don’t want to squander that,” Stevens said, noting that CARTA is used by 95 percent of undergraduates.

“Students are almost uniformly enthusiastic,” Stevens said. “We have a feedback button on the site. Overwhelmingly people thank us for the platform and make positive suggestions.”

Stevens emphasized the importance of students to the site.

“They’re our primary constituents and we’re committed to that,” he said. “We think students deserve to make academic decisions in information-rich environments.”

The paper did not provide any definite explanations as to why CARTA lowers students grades.

“Our study design prevents us from identifying the psychological mechanisms through which information about official course outcomes is translated into changed academic behavior and performance. Course outcome information could influence behavior through a variety of pathways, such as motivational or self-regulatory processes,” the report read.

Stevens speculated that a high grade distribution could lull students into complacency.

“One hypothesis is that students come to Stanford recognizing and kind of expecting Stanford to be challenging,” Stevens said. “[Students] look at the grade distributions and see that the majority of their peers got A’s or A-’s, and they may relax a little and over presume that they’re going to get high marks.”

He also acknowledges, however, that the opposite is also possible.

“Students may be intimidated by the grades they see and under invest in a stereotype threat type of way,” Stevens said. “We just know there was a substantial and causal relation between exposure to grade information and subsequent GPA.”

“Often times you see classes with great grade distributions and you tend not to work as hard,” Bocar Wade ’21 said. “French has a really high grade distribution. It gets a lot of A’s, so I don’t practice French as much as I should because of that. I’m doing completely fine, but I feel like if I didn’t see [the grade distribution] I’d probably work harder.”

The study found that while CARTA lowers students grades, it does not affect course enrollment. CARTA does not have a measurable influence on which courses students chose to enroll in. Instead, CARTA only affects the performance of students within their selected courses.

Despite CARTA’s negative impact on GPA, it still levels the course selection playing field for all students. The report notes that without CARTA, information about courses travels along social networks and that “likely exacerbate[s] information disparities by race and class.”

“A lot of time you base your classes off a network of what your friends have taken,” Wade said. “CARTA is good in that it provides you with a bigger range of opinions than those around you.”

Stevens agreed, citing peers as the main source of information used by students when determining class selection.

“If I’m on the swim team, for example, a great deal of my information is going to come from other members of the swim team, but that biases the information that I get,” Stevens said. “That’s not necessarily a bad thing except the academic options that are available to students at Stanford are much larger than the ones talked about among particular groups of their peers,” Stevens said.

CARTA reduces this reliance on friend groups by making course information easily accessible. It’s a trend familiar in the operations of many Silicon Valley companies.

“There’s a fundamental information equity issue that CARTA addresses,” Stevens said. “In a world of Yelp, and Facebook and Google searches, people just expect more and better information. I think that’s happening in higher education as well.”

Contact Nicholas Midler at namidler ‘at’ stanford.edu.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly spelled Stevens’ name once. The Daily regrets this error.

This article has been corrected to reflect that the study measured GPA declines by standard deviations, not by points. The Daily regrets this error.