As a part of its initiative to further research in biology, chemistry and material sciences, the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University unveiled one of the world’s most advanced cryogenic electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) facilities in January. Cryo-EM helps scientists gain access to unprecedentedly detailed and accurate images of cells and biological molecules.

Cryo-EM machines are the result of more than 40 years of research into refining and simplifying biomolecular imaging. Their development has made it possible to generate images of complex protein structures and has assisted in drug development for the likes of the Zika virus, HIV and cancer.

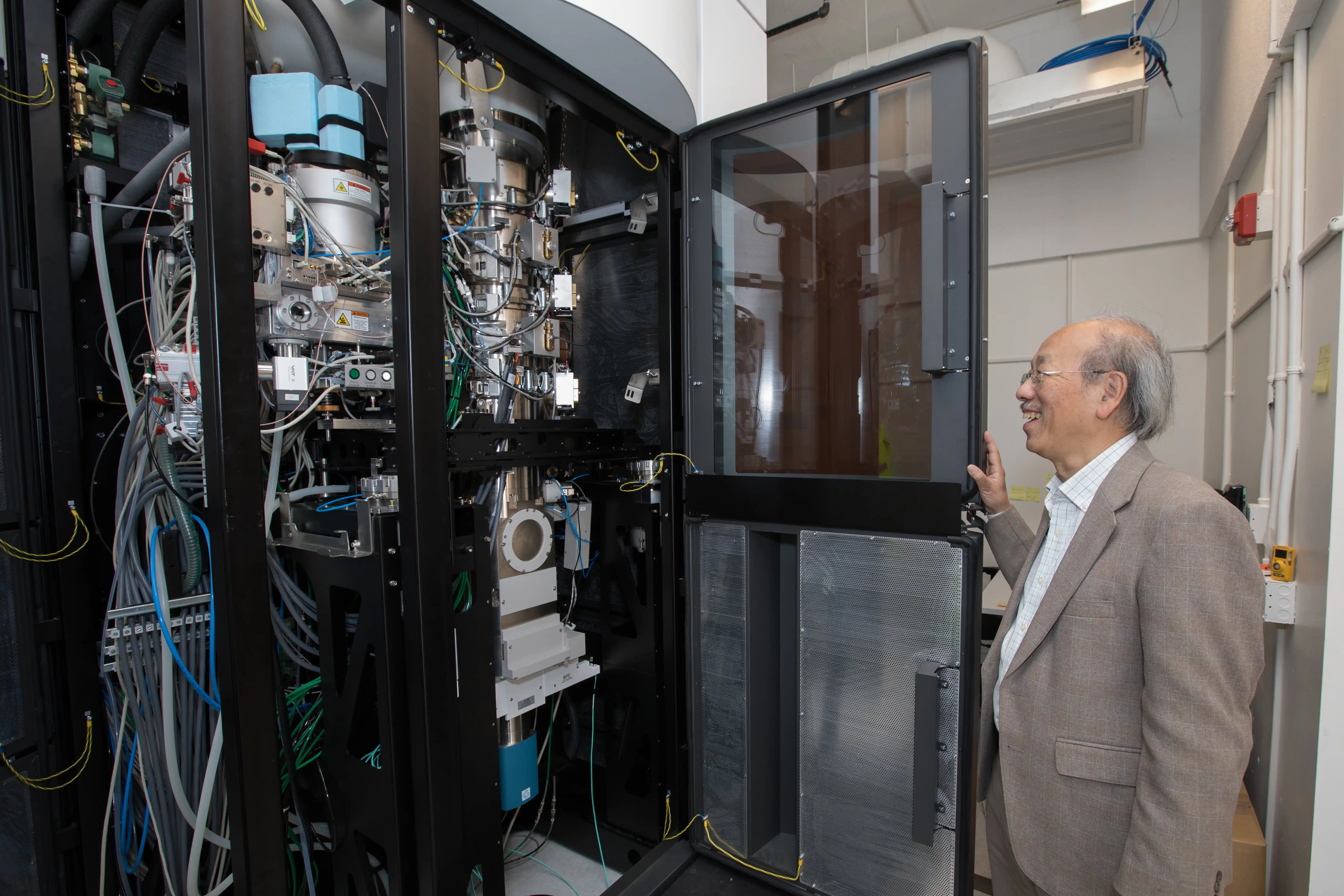

“You can now see close to atomic resolution,” SLAC Director Chi-Chang Kao said. “Seeing something is very powerful.”

SLAC installed four Cryo-EM instruments and included a number of rooms to prepare samples for imaging. The molecules are placed on 3mm by 3mm specimen support grids and rapidly frozen.

According to bioengineering Ph.D. candidate Patrick Mitchell, 2D images of atomic resolution are created in a process known as cryo-electron microscopy, during which electron beams are shot at the samples. Using computers, the images are then combined to create 3D images of different molecules including proteins, viruses and nucleic acids.

“We can answer questions like how they look and where they are [in cells],” said bioengineering professor and lead researcher at SLAC’s Cryo-EM facility Wah Chiu. “You can get information you could not get before.”

Up until now, the majority of 3D biomolecular imaging was done using X-rays on crystallized biomolecules. According to photon science and structural biology professor Soichi Wakatsuki Ph.D. ’91, crystallization of complex biomolecules is a relatively difficult process.

“The molecules need to be exactly the same,” Wakatsuki said. “There is a limit with what we can do with X-ray crystallography.”

Cryo-EM allows for cell mapping without having to form crystals, which makes it possible for researchers to view more complex structures in a cellular context.

Because the image resolution from Cryo-EM is so high, any sort of specimen or stage movement can ruin the image. As a result, SLAC spent almost two years preparing the new facility.

“The floor has to be extremely stable and the room has to be free of electromagnetic noise,” Kao said.

Even now, researchers using the lab must be extremely cautious to minimize disturbance.

“We [researchers] need to be very careful,” Mitchell said. “We close all doors, stay out of the room and even turn off the light to make sure its electromagnetic radiation doesn’t interfere.”

The Cryo-EM facility has received interest from biologists and pharmaceutical companies alike.

“There is already a long line of people waiting to use the facility,” Chiu said. “Drug designers and vaccine developers can use [structural] information from Cryo-EM for drug development.”

SLAC recently earned a grant from the National Institute of Health that will allow it to double the size of its Cryo-EM facility and and increase its accessibility.

“We want to help the science community [across the country],” Wakatsuki said.

A previous version of this article lacked/misrepresented certain details which have been corrected in the current version. The Daily regrets this error.

Contact Manat Kaur at manat ‘at’ object.live.