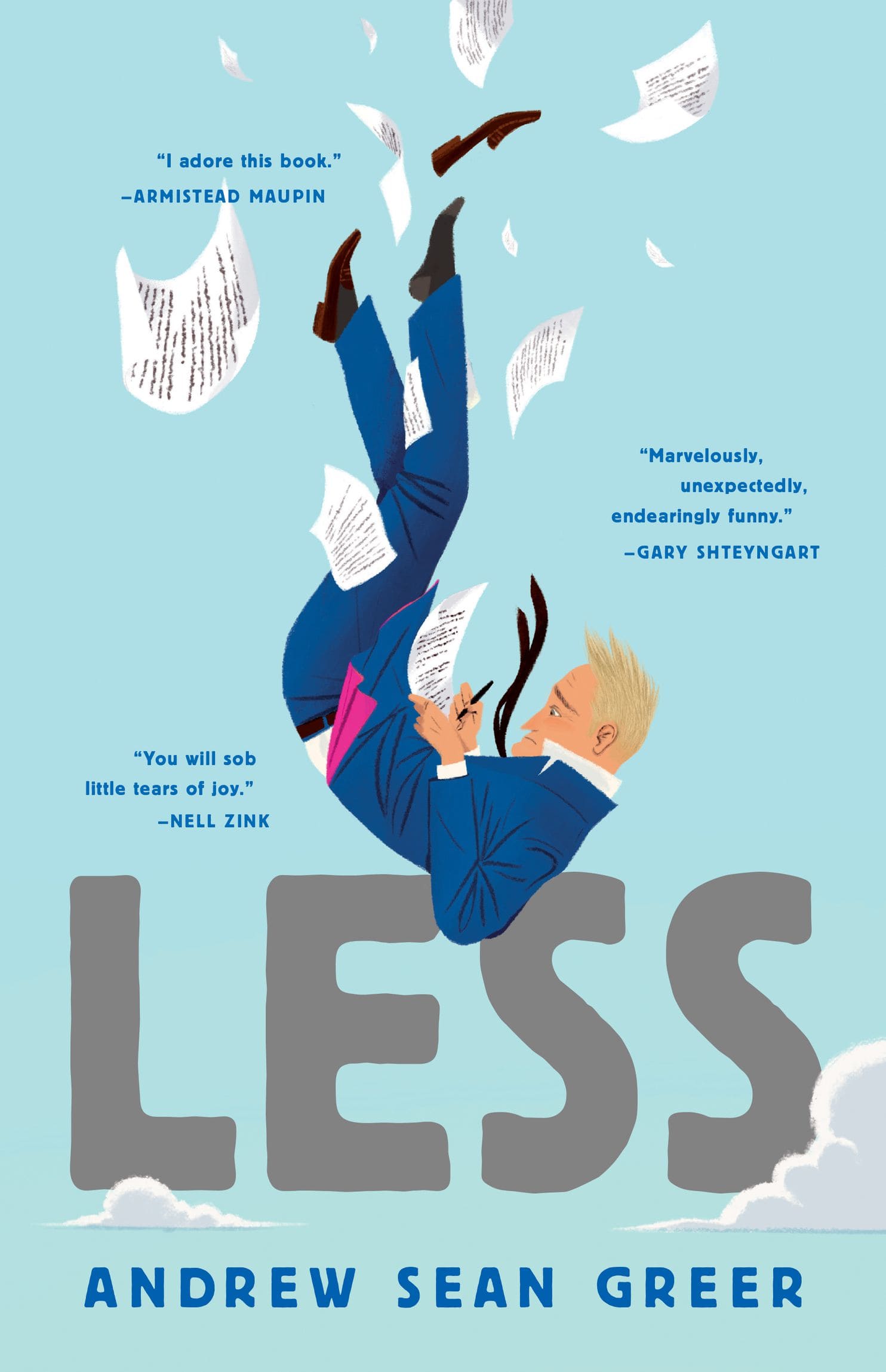

Continuing from yesterday’s paper, this article is Part 2 of staff writer Gracie Newman’s interview with Andrew Sean Greer, who is the author of “Less” (the 2018 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction) and numerous other novels and short stories. “Less” is a comedic romance that follows a middle-aged writer as he travels the world in an attempt to avoid attending the wedding of the young man with whom he is in love. With what The New York Times describes as “sentences of arresting lyricism and beauty,” the book explores the intricacies and intersections of love, vocation and exploration with admirable — and necessary — optimism. Greer resides in San Francisco with his husband and his pug.

Gracie Newman (GN): So I’m sure you get this question a lot, but the Pulitzer must have been in some ways a validation of your work. Even with the character of Robert in “Less,” you explored the idea of literary genius, what it’s like to live with a genius, how that term is defined, etc. What is the most unexpected consequence that came from winning the most respected literary prize in the world?

Andrew Sean Greer (ASG): Oh, that’s a good question! A lot of things I expected [came] out right off the bat. I thought, “Maybe I’ll make more money now,” or “Maybe people will recognize me or have heard of my name” … I expected that. I think it is in myself. I don’t mean to seem incredibly insecure, but the other day, I was doing an event with Tina Brown and Susan Orlean. An emergency came up, and I needed to contact them, and I thought, “No problem, I’ll just write them.” Before I would have felt like someone’s assistant calling up and being like, “Hi, I’m a writer you haven’t heard of but…” But now it doesn’t matter if they’ve heard of me. That confidence surprised me. Now I don’t need anything from them, and so now it’s not fraught for any of us.

Another consequence I’ve come up with a little bit — Jennifer Egan, I did a reading with her, and I asked her advice. She said, “You know you’ll have to treat people really decently from now on. There’s this strange wall between you — certainly with a beginning writer, maybe with you, I don’t know — there’s this strange magic wall they’ve built in their head around you, and you aren’t aware it’s there, but you’re the only one who can take it down. What you can’t be is dismissive — you have to take everyone really seriously because they’re watching you more than they were.” Now luckily she’s a really decent, good person, and I hope I am too, but I keep that in mind that I have some responsibility. I know having met famous writers when I was young — they didn’t mean anything by it, whatever they did — they were just not paying attention, and I remember it still. You know, it hurt me, and it didn’t mean anything.

You can’t fake it. If you’re an asshole, and you win an award, you can be like, “Thank god, now I can just not give a shit what I say to people.” I’m sure people have done that. Maybe it’s a test to see if I’m really an asshole. But I did learn a lesson a long time ago — I had some success with my third book, and I was really full of myself. Daniel Handler and I, I remember we were meeting at the Makeout Room, and there was a poet who we both knew who was handing out her chapbooks that she’d printed herself of her new poems. We’d had a couple manhattans, and I was like, “This is the life, Manhattans with Daniel Handler, I’ve made it!” And when I left, he said, “Andy, you forgot your chapbook.” And the way he said it made me understand that maybe it’s shitty poetry, but you do not leave it on the table like it’s nothing. You take that person seriously, and you thank them for it, and you take it with you. You do not dismiss other writers who are not at the moment as celebrated. He taught me that lesson in that one moment, and I’ve never forgotten it. I was really embarrassed about it, that I was like, “Ugh, I’m not taking that.”

GN: While he travels the world, Less is generally treated kindly by the people he comes across. It’s a very optimistic view of human nature. How do you acquire your characters? How close do you get to your own life?

ASG: I did invent every character, but one of the rules I made for myself while traveling was that I could only put detail in what I wrote down in my notebook. That kept me from making fantasies about these countries or these people. I have found traveling that people are surprisingly decent. Of course, I’m a tall white man, so I’m not usually in danger. When I stay in one place for a while, then I meet the less lovely people. Travel is about taking chances, being uncomfortable, challenging yourself and being open to surprises. I’ve gathered the pleasant surprises in my head. When I would travel to write the book, I would think about how I would tell it to my friends and how I would make it a good story. And, since I’m making it up, what would I add? Nobody wants to hear you complain about traveling to Japan; it’s only good if it’s a funny story. It was the only way I could write it. It’s like telling your friends a story because they don’t want to hear you complain; they’re working at their terrible jobs, and they want a funny story.

I think it comes from my own anxiety about other people. I’m very awkward with strangers; it’s my biggest challenge that I try to overcome in all kinds of ways because it pays off, but it’s super hard for me. And travel is one way because I’m so vulnerable, because I don’t know anything. I have to be open … If I’m lost, I’ve got to take whatever help comes my way, and I would not do that normally. I would try my app … but there was no app in India.

GN: It’s been suggested that your book winning the Pulitzer means that what has previously been considered a subgenre, “queer literature,” has finally become mainstream. It’s no longer relegated to a separate section of the bookstore. What are your thoughts on this?

ASG: Really? I don’t think now it’s a separate part of the bookstore at all. Certainly when I was back in college it was secretly in the back, and it wasn’t called “queer.” It was gay and lesbian, which is pretty limited, considering. And it meant that you were not in the regular section. I remember for my first two books going to Powell’s in Portland on a book tour, and my book was in the gay/lesbian section and not in the regular fiction section, and it broke my heart. And why would you do that? So it’s not available to anybody but gays and lesbians? And Amazon, they did that for my fourth book, so it happens online too! They decided that all gay and lesbian fiction was erotica, so they made it all invisible unless you searched for gay and lesbian literature. That was about 10 years ago, and there was nothing I could do about it. It made you realize that other people are categorizing what you do, and it’s unpleasant. I love the idea that Less brought queer literature into the mainstream. I just love that idea. I love the idea that so many people are reading a same-sex love story where things don’t go tragically at the end, and they’re picking it up as one of their ordinary reads. I just can’t believe it.

GN: If you could recommend three books to college students right now, what you would you recommend?

ASG: Oh my god that’s so hard! I like really old books. I find them really interesting because they’re out of fashion. If you read old books, it’s really good for your writing because they do things that no one is doing now because no one is reading them. You get all this influence that’s just new. If you just read the bestseller list, they start to all sound the same, and nobody wants that.

I would recommend “The Portable Dorothy Parker.” That was my favorite book in college because she’s so hilarious and so biting. And “A Hundred Years of Solitude,” you must read that. I don’t know what’s on the syllabuses right now, but I would recommend something that is totally forgotten and not read. I think it might be interesting to read “Mrs. Caliban” by Rachel Ingalls. It’s just nuts; it’s so brilliant.

Sometimes in college people forget that reading is fun, that it’s a pleasure. I would say something like “Rebecca” by Daphne Du Maurier or a Raymond Chandler novel because they’re so beautifully written, but they’re also very focused on giving the reader the pleasure of a spooky thriller or a detective novel. It’s important to remember that you’re allowed to make something happen in your book. You can have a jewel heist, that’s perfectly fine. We would all kind of rather have that than just a marriage falling apart.

When you read a lot of great fiction in college, you think that it’s supposed to all be moody, but you have things happen. You can have a giant monster come of the sea and attack everybody, that could be a literary book. It’s a challenge, but it might be a fun one.

For my grad students, every year I would take the class to the used bookstore in Iowa. I gave them each five dollars, and I said, “You have to pick a book you’ve never heard of. You’re picking completely based on the cover, the title, the first few lines” … I wanted them to get out of the groove of this sort of groupthink way of deciding what’s good in literature.

GN: I was hoping we could delve a little more into the prose. “Less” is so musical with its spunky and vivacious language, and it seems like it would be really fun to write. Do you think that the genre gave you more freedom to play with words, or was it the nature of the narrator, the characters?

ASG: I’m old enough to know my strengths and weaknesses as a writer. One of the weaknesses is an indulgence in elaborate language, which in a comedy can be a strength, because I would just overdo it and enjoy myself and hopefully make it a funny sentence instead of a ponderously important one. I was really influenced by two books while writing, one was Nabokov’s “Pnin,” which I really stole from. And Updike has a bunch of books about a writer called Bech. They’re both comic novels. “Less” is different from both of them, but I read them both constantly to remind myself of where I was supposed to be, which was having a good time.

GN: Maybe I’ll have to give Updike a try. I read a David Foster Wallace essay once that just tore him apart, and I’ve stayed away since.

ASG: I don’t know what I would recommend. He’s so bad at writing women. Roth also, he’s such a good writer, but it’s just really hard to take. They clearly just don’t believe women are human beings or something? It doesn’t come across. They don’t manage to create real characters. It’s a real shame. There are these women, and they’re just always thinking about their breasts. But see if you can catch his fun with language — that’s what stuck with me.

GN: There’s a lot of discussion about the valuation of the art versus the artists today, and about how and whether you can separate them.

ASG: If you decide that if it’s just for you, it’s not going to do damage to you, and especially if you’re like, “I’m going to steal from it, learn from it and discard it,” then you have mastery over it in some way. I don’t know if Philip Roth ever knew a gay man knowingly. We don’t show up in his literature very much, but I’m not put off because I’m so interested in how he tells stories. But I would have to think a long time about putting it on a syllabus or telling you that everyone should read it. That feels separate, like celebrating it.

GN: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

ASG: Just from in my workshop days, and I take this advice myself: I would find that a writer would turn in a story. It would be a marriage slowly falling apart, and then at the end there’s a mermaid. And the class would say, “Cut the mermaid, and it’ll be great.” But I would say no, keep the mermaid and fix the rest of the story to fit the mermaid. The weird thing about the story is the thing that has to stay. It’s the only reason you wrote, the thing you discovered on the way. A committee or a workshop will want to get rid of that and make it mediocre. An editor will too. It happened with “Less” also. I love my editor, but there were things that she wanted to cut, and what I heard was that they weren’t working. It was then a challenge for me to fix the rest of the book to make those parts work. It’s taken me a long time to learn that.

I learned this the other day when I went to the secondhand store up the street. I said, “I only wear one tie. I own others, but I only wear one. I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” And the guy said, “That is because you’re putting on your suit and your shirt, and then you are going to look at your ties.” Only one fits because you’ve already made all these other choices. “Start with the tie,” he said. Start with the tie. What you always have to do is commit fully to the strange thing that doesn’t fit. Commit all the way to it, and you’ll have a great story, but take it out and you’ll have a mediocre thing.

Whatever you are, commit totally to the thing that you are trying to hide. That’s a better way to be. Maybe that’s a queer philosophy, I don’t know. Whatever you think your flaw is, like if you have a big nose, totally celebrate it! Don’t contour it away. Celebrate it, and you’ll come off as beautiful, but you really have to own it. And I think it’s true in literature. Let it be what it really is, even if it’s not what you hoped it was going to be.

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Contact Gracie Newman at sgnewman ‘at’ stanford.edu.