“Look,” Layli Long Soldier commands us in the title of one of her poems in her book “Whereas.” When we follow her instructions, we see “the light / grass / body/ whole / wholly moves,” and so on. This poem — with lines mostly consisting of one or two words and immense amounts of space between each line, while spanning over three pages — is jagged when I read it. I find myself stumbling over each line, unable to put together the image without extreme focus. I end up staring at these otherwise familiar words until they make sense. “Look,” Long Soldier commands. “I’m trying,” I gasp. “Really, really hard.”

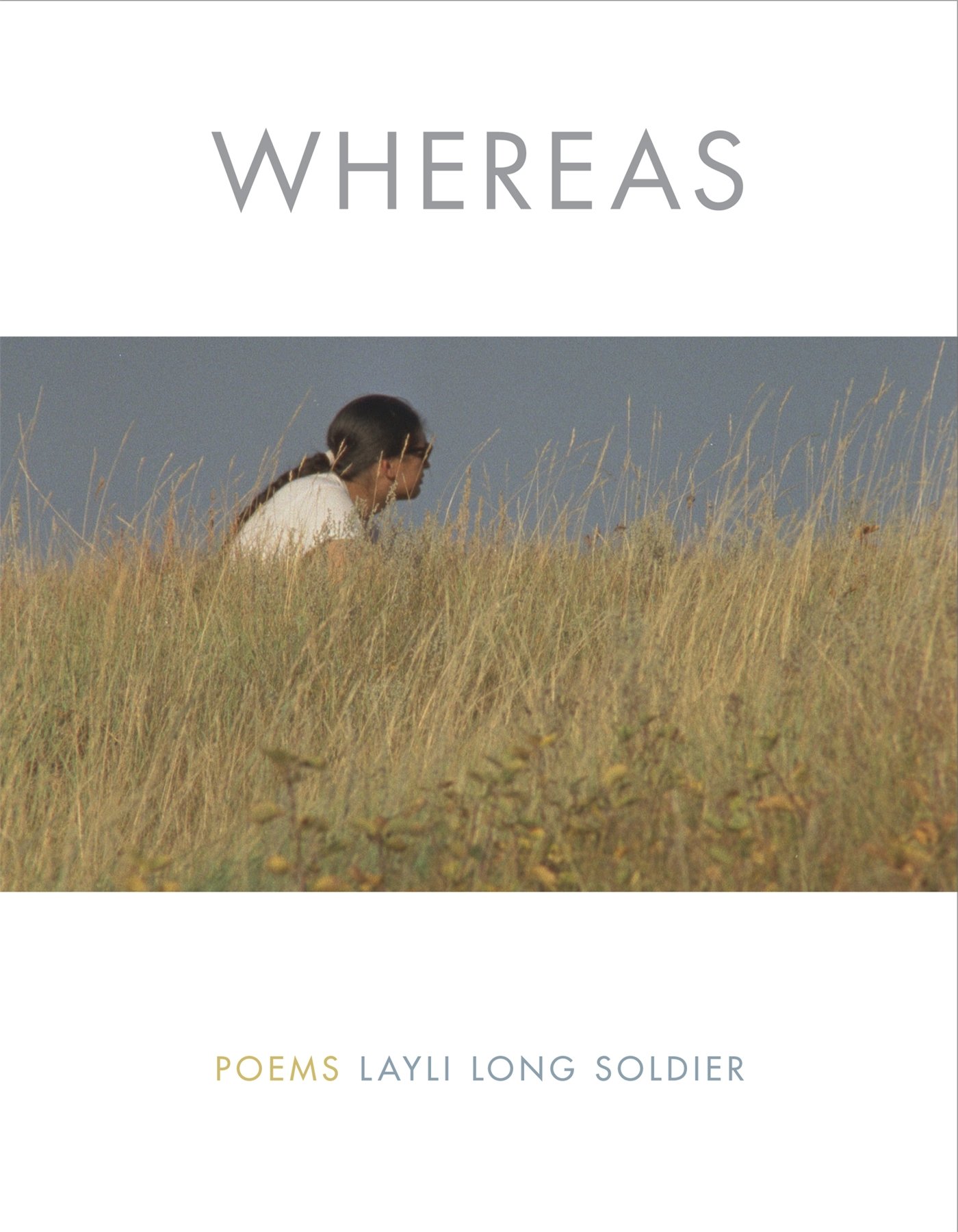

“Whereas” is Long Soldier’s 2017 award-winning collection of poetry, but it is also a response to S. J. Res. 14 (2009-2010): a congressional apology and resolution to American Native Peoples. The apology was passed, but it was never acknowledged by President Barack Obama, and it includes a clause that protects the United States from being legally liable for anything admitted to in the apology. Long Soldier demands a close re-inspection of the language of this resolution, finding the violence in it — a violence hidden by familiarity and complacency. Her book is a slow burn, and much of its power comes from the way each subsequent page builds on the last.

In the first section of her book, titled “These Being the Concerns,” we are introduced to Long Soldier’s poetic and linguistic framework. Her poetry is startling — often, she splices lines with unexpected spaces, cuts words in half at the line breaks, or makes us read in non-linear ways. In one section of “Diction” titled “leftist,” each line contains only two syllables. In “Wahpanica,” she replaces every comma with the literal word “comma.” These little adjustments to how we regularly conceive of language accumulate over the book as the reader relearns how to read. Each word is deliberate; each word is called into question, defined, examined, redefined, re-examined.

Then with her poem “38,” Long Soldier breaks from this unusual pattern, but the result is even more jarring. She reverts back to conventional ways of writing: “Here, the sentence will be respected. / I will compose each sentence with care, by minding what the rules of writing dictate.” The poem “38” is an account of the Sioux Uprising, during which 38 Dakota men attacked settlers who were taking their land and starving their people, and thus were hanged under orders of President Abraham Lincoln. How else can we tell this story, and so many others recounting the atrocities committed against Native Americans? Long Soldier claims in “38” that “I do not consider this a ‘creative piece.’” Any other form of expression — short story, abstracted poem, dramatization — would obscure the truth of history.

“38” leads the book into Part II, titled “Whereas.” Legal documents such as S. J. Res. 14 often use the word “whereas” to mean “taking into consideration the fact that.” But Long Soldier complicates this definition of the word, which in our colloquial usage implies a contrast or comparison. By thoroughly deconstructing the very language of the resolution itself with her “Whereas Statements,” she exposes its flaws, its missing links, its leaps and assumptions and omissions.

The governmental apology is filled with big, fancy, and empty words — it is not really an apology at all, but instead a meaningless document without substance. Conversely, Long Soldier’s own whereas statements are self-conscious, self-aware, and inquisitive. Yet ultimately hers do not constitute an apology either; her work is a repudiation of apology that reflects exactly what the United States government gave her. Just as S. J. Res. 14 refuses liability, Long Soldier places blame away from herself: “Nothing in this book-/(1) authorizes or supports any claim against Layli Long Soldier by the United States; or/(2) serves as a settlement of any claim against Layli Long Soldier by the United States, here in the grassesgrassesgrasses.”

Contact Lily Nilipour at lilynil ‘at’ stanford.edu.