Former Stanford President and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Donald Kennedy died of COVID-19 on Tuesday morning.

Kennedy, 88, was living in Gordon Manor, an assisted living facility in Redwood City that has recently been struck by a COVID-19 outbreak. In addition to Kennedy, at least two other Gordon Manor residents have died of the disease, according to the San Mateo Daily Journal.

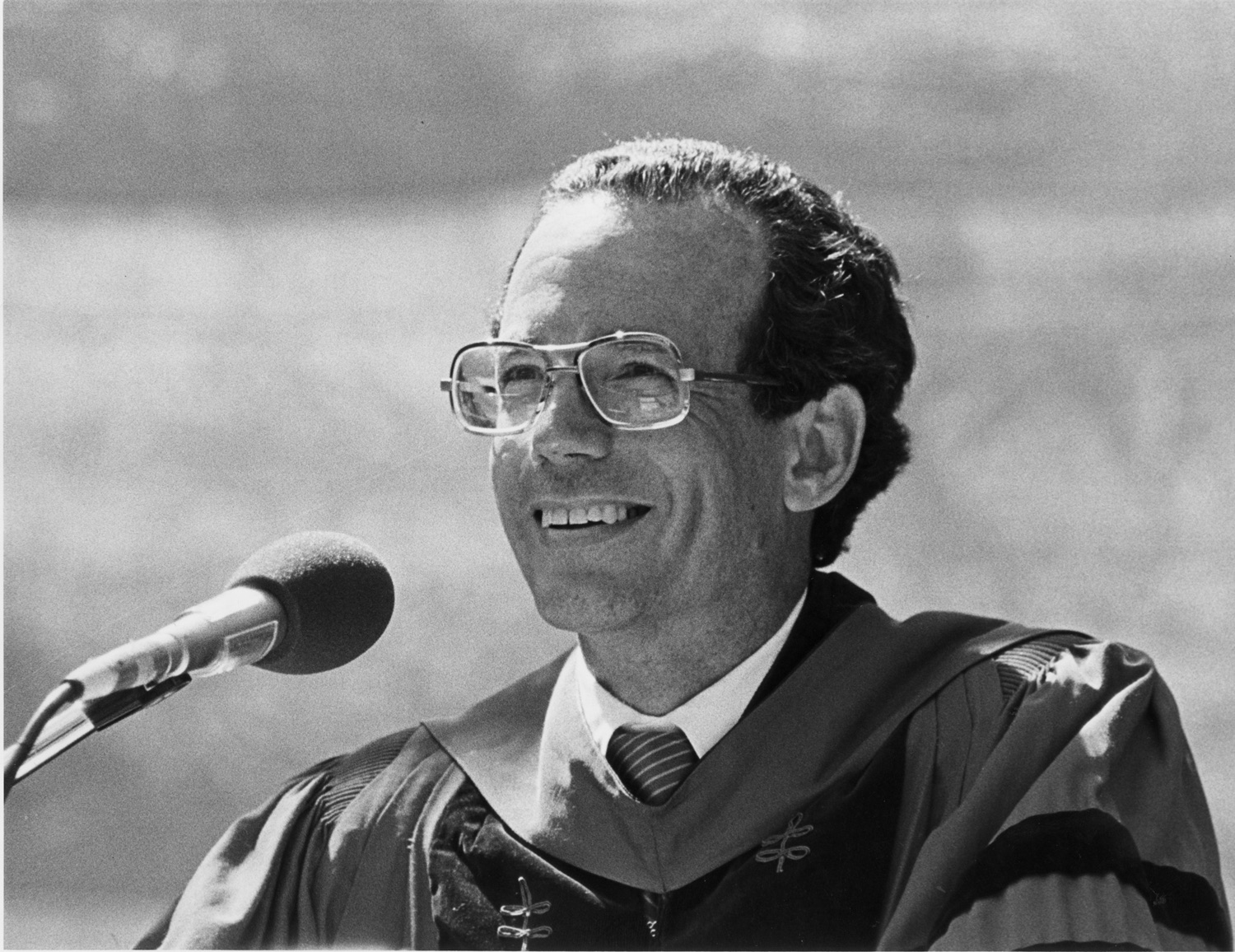

Kennedy, Stanford’s eighth president, led the University from 1980-92, the culmination of a 32-year career at Stanford in which he also directed the human biology program and chaired the biology department. From 1977-79, he took a leave of absence from Stanford to lead the FDA during Jimmy Carter’s presidency. After stepping down from the president’s post, he served as editor-in-chief of Science Magazine from 2000-08.

San Mateo County has deployed a team of clinicians to the Gordon Manor facility to help curb the outbreak. The county issued a health order on Wednesday instituting new rules to protect residents of facilities that care for the elderly, including restricting visits from family members.

Robin Kennedy, Donald’s wife, praised Gordon Manor for its handling of the outbreak, writing in an email to The Daily that the facility “promptly, significantly, and expertly upped its game.”

“My husband was not alone in his room any time during the days of his illness,” she wrote. “When he took a turn for the worse on Saturday night, a family member was with him holding his hands, massaging his face, talking to him and reminding him how much he was loved by his family. Our (adult) children and I and two of our grandchildren were able to ‘be present’ on Sunday evening, via FaceTime.”

“It gave each of us a chance to say goodbye,” she added. “That was the single most valuable service Gordon Manor provided.”

‘A cultivator of enthusiasm’

Kennedy joined Stanford as an assistant professor who gave up the status of associate professor at Syracuse to join The Farm. At 35 years old, only seven years after joining the faculty, his passion for biology combined with leadership skills helped him to become one of the youngest chairs of a Stanford department.

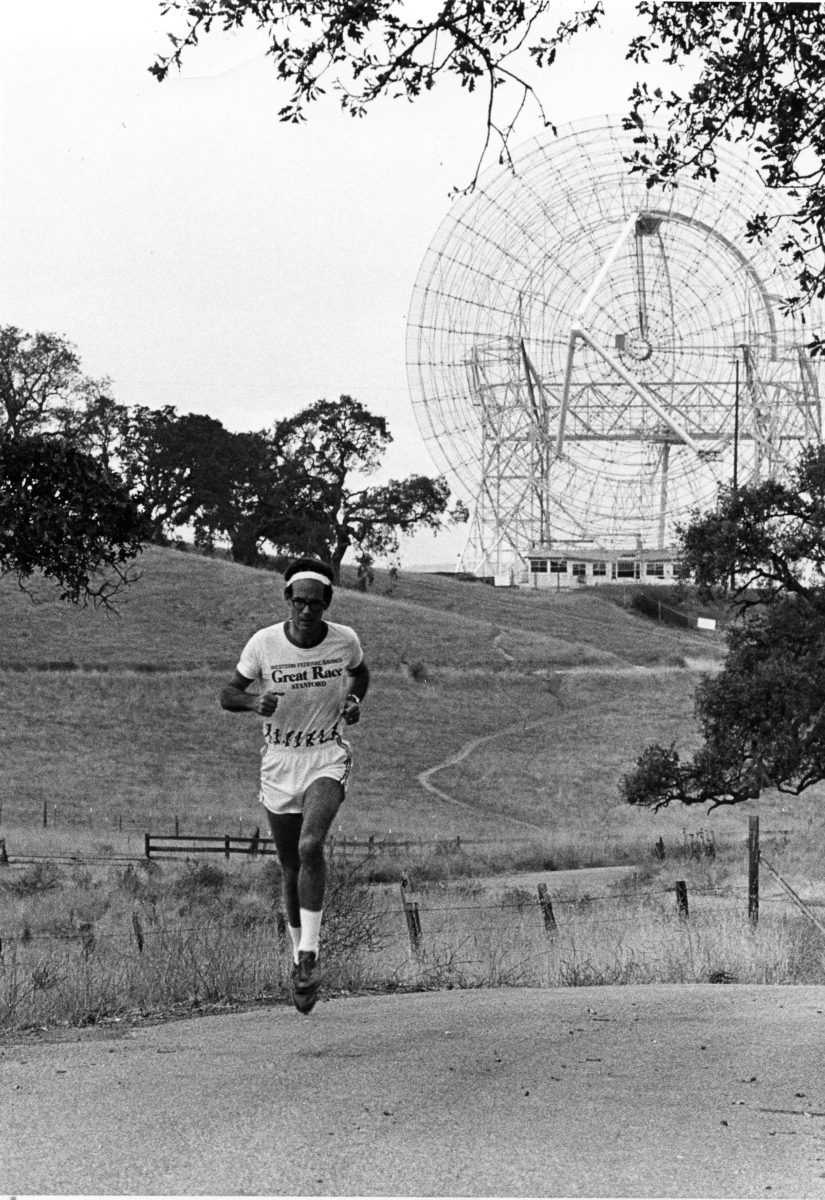

Jeanne Kennedy, his first wife, described him as a charismatic leader, full of energy, both physical and intellectual.

“He was one of those triple threat guys: brilliant teacher, brilliant researcher and brilliant administrator,” she told The Daily.

“He always had his door open,” she added. “For example, he used to extend an invitation for the students to join him on the daily run at 6 a.m.”

As University president, Kennedy served as a freshman advisor, spoke on KZSU, visited dorms, attended athletic events and gave lectures for human biology core classes, leading to a reputation as an accessible and popular leader among students. Kennedy also prioritized re-envisioning undergraduate education. He allocated $7 million in programs to improve undergraduate teaching and established the vice provost for undergraduate education position early in his tenure.

“I want to be a cultivator of enthusiasm and a good agent of consensus,” Kennedy told The Daily shortly after becoming president.

And while he easily fulfilled the former goal — his first provost Albert Hastorf told The Daily in 1991 that Kennedy “maximizes people through his own energy” — his bold and self-confident leadership style proved to transcend “consensus” in driving change during his 12-year tenure.

Jeanne Kennedy fondly remembers her ex-husband’s charisma, as well as universal respect for all campus residents, as reasons for his popularity.

“He was the kind of person who could make you feel like you were the only person in the room,” she said. “He could always see the best of someone, who they really wanted to be. He could see it, respond to it, and make them feel as if they were that best version.”

Lamenting in his inaugural address that the “earthy western pragmatism” that “animated the founding years” of Stanford left it with a utilitarian mindset that prioritized the sciences, Kennedy focused his efforts on building up the humanities as he moved Stanford through its centennial. He established the Stanford Humanities Center and expanded humanities faculty, The Daily reported four years into his presidency.

Kennedy also worked to expand Stanford’s international presence. He opened Stanford’s campuses overseas in Kyoto and Oxford, programs that still run today. Responding to widespread student protest, Kennedy led the University to divest in 1985 from companies that supported the apartheid regime in South Africa. He also oversaw the establishment of the Institute for International Studies as well as the Stanford in Washington program.

“The world is full of institutions that tend toward inertia,” journalist and former Stanford Trustee Doyle McManus ’74 told The Daily in 1992. They need, he added, “certain kinds of leaders to give the institution a big shove.”

Public service was also a priority during Kennedy’s presidency. After an evaluation of the state of campus community service in 1983 concluded that the University lacked institutional support to encourage service among students, Kennedy oversaw the establishment of the Public Service Center in 1985. In 1989, it became the Haas Center for Public Service, honoring the contribution of the Haas family to its founding endowment.

A decade into his presidency, Stanford made national headlines when congressional investigators found that the University had used federal money intended for research toward his personal expenses, including an antique commode, a yacht and floral arrangements. The issue was settled out of court, and the University was exonerated.

In the fallout, Stanford suffered a $43 million budget deficit after federal funding was cut back, and Kennedy resigned shortly thereafter. That fiscal damage, however, was followed by what was then the most successful capital campaign in higher education: the Stanford Centennial Campaign, which raised $1.3 billion.

Senator and former presidential candidate Cory Booker ’91 M.A. ’92 (D-N.J.), saw Kennedy as a mentor, and was inspired by how he handled the controversy, despite the scrutiny.

“To watch him leading through the indirect cost crisis, through professional and personal attacks, under tremendous stress and strain, with clouds amassed over his head and discipline raining down on him, was a study in leadership, character, and discipline, always better shown in times of crisis than when all is going well,” Booker wrote in the foreword of Kennedy’s memoir, “A Place in the Sun.”

Always a scientist

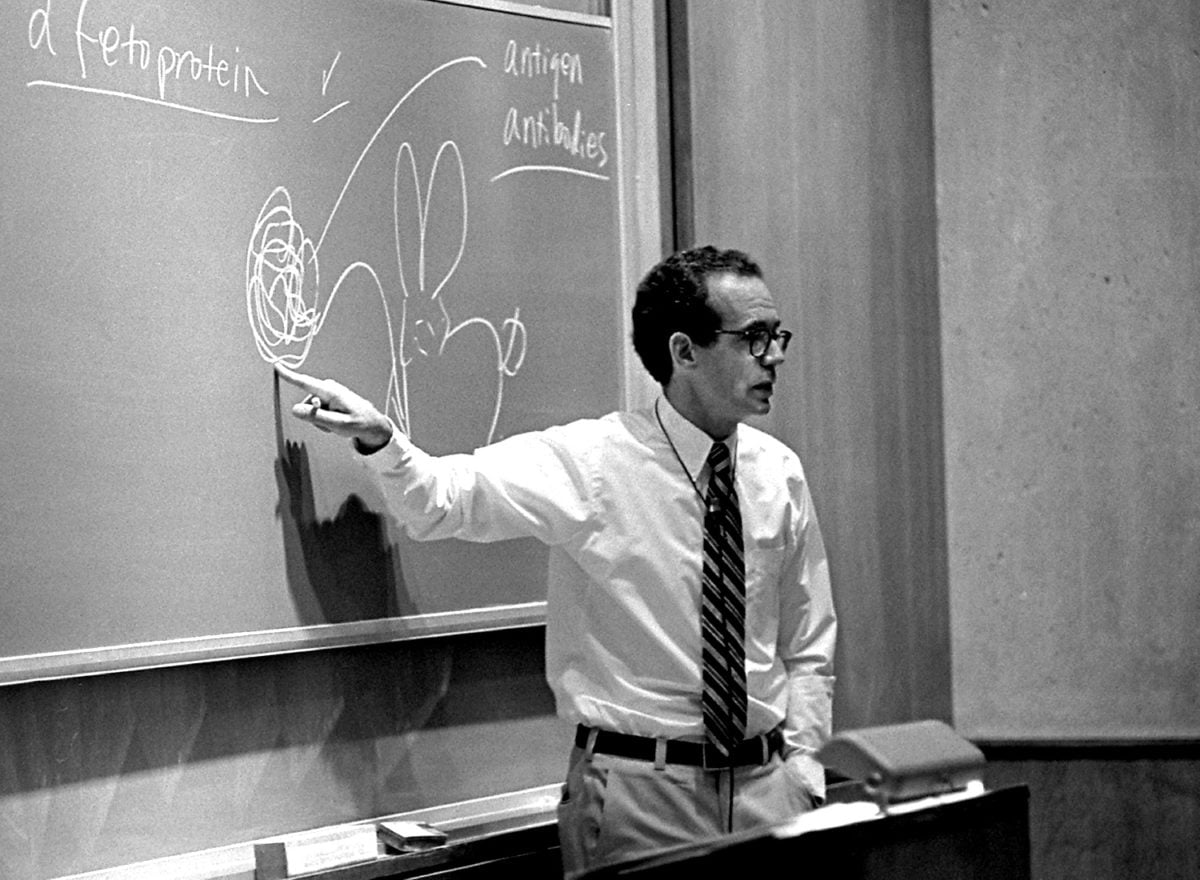

Long before Kennedy became University president, he was a neurobiologist, earning his bachelors, masters and doctorate degrees in biology from Harvard. At Stanford, he helped establish the human biology program, and he frequently guest lectured for its core classes — though he insisted this wasn’t teaching.

“Teaching,” he told The Daily in 1989, “is when you plan a course; you invite some other people in to lecture; you create an intellectually coherent and stimulating whole; you develop readings; you develop challenging examinations; you write and you grade them; you read people’s papers and you write in the margins — that’s teaching.”

Kennedy earned the Dinkelspiel Award for excellence in teaching in 1976, before making teaching excellence a primary focus during his presidency.

In his own scientific research, he focused on the properties of small nerve cells, finding that stimulation of single nerve cells in crayfish can prompt complex motor activity. He later created a new technique of dye that makes the axon, dendrites and cell body of a nerve cell visible under a microscope.

Kennedy was also concerned with public attitudes toward science. After urging his students to apply their knowledge to public service, he decided to take his own advice and take a hiatus from Stanford to serve in the FDA, where he fought to ban saccharin due to its potential cancer-causing effects. He was ultimately unsuccessful, but was well-respected for his efforts.

He changed the way people looked at the FDA by bringing academic flair to it and attempting to equalize its political effect with real-life impacts the agency had.

“He used to say that the FDA was hit so often because it was a slow-moving target,” Jeanne Kennedy said. “It was low on the hierarchy of the political effect and he brought it into real prominence.”

During his time as Science editor-in-chief, Kennedy attempted to stir the publication in a progressive direction. Through his weekly editorials he aimed to “tackle truly controversial issues involving science: climate change, stem cell research, bioengineering and government secrecy” as he described in an interview to the Stanford Report. Bold decisions led to some controversy. In one of them, the journal published and then retracted an article by Woo Suk Hwang, an infamous South Korean researcher who was later accused of fabricating data.

His experience as one of the few academics in the FDA allowed him to push Science towards a policy-shaping approach through weekly editorials.

“I plan to work a little bit more in Washington with people who are in policy circles, to get them to understand what we’re trying to do, because I think the scientific community really needs a voice in helping to develop science policy,” Kennedy said in an interview with Stanford Report.

Kennedy’s impact lives on at Stanford in the Haas Center for Public Service and the University’s support for the humanities, and beyond in FDA and the scientific community.

“Of course, everybody has some faults but he was a comet that blazed across the sky,” Jeanne Kennedy said.

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Kennedy was the youngest chair of a Stanford department. He was one of the youngest. The Daily regrets this error.

Contact Julia Ingram at jmingram ‘at’ stanford.edu and Anastasia Malenko at malenk0 ‘at’ stanford.edu