CW: Mentions of sexual assault

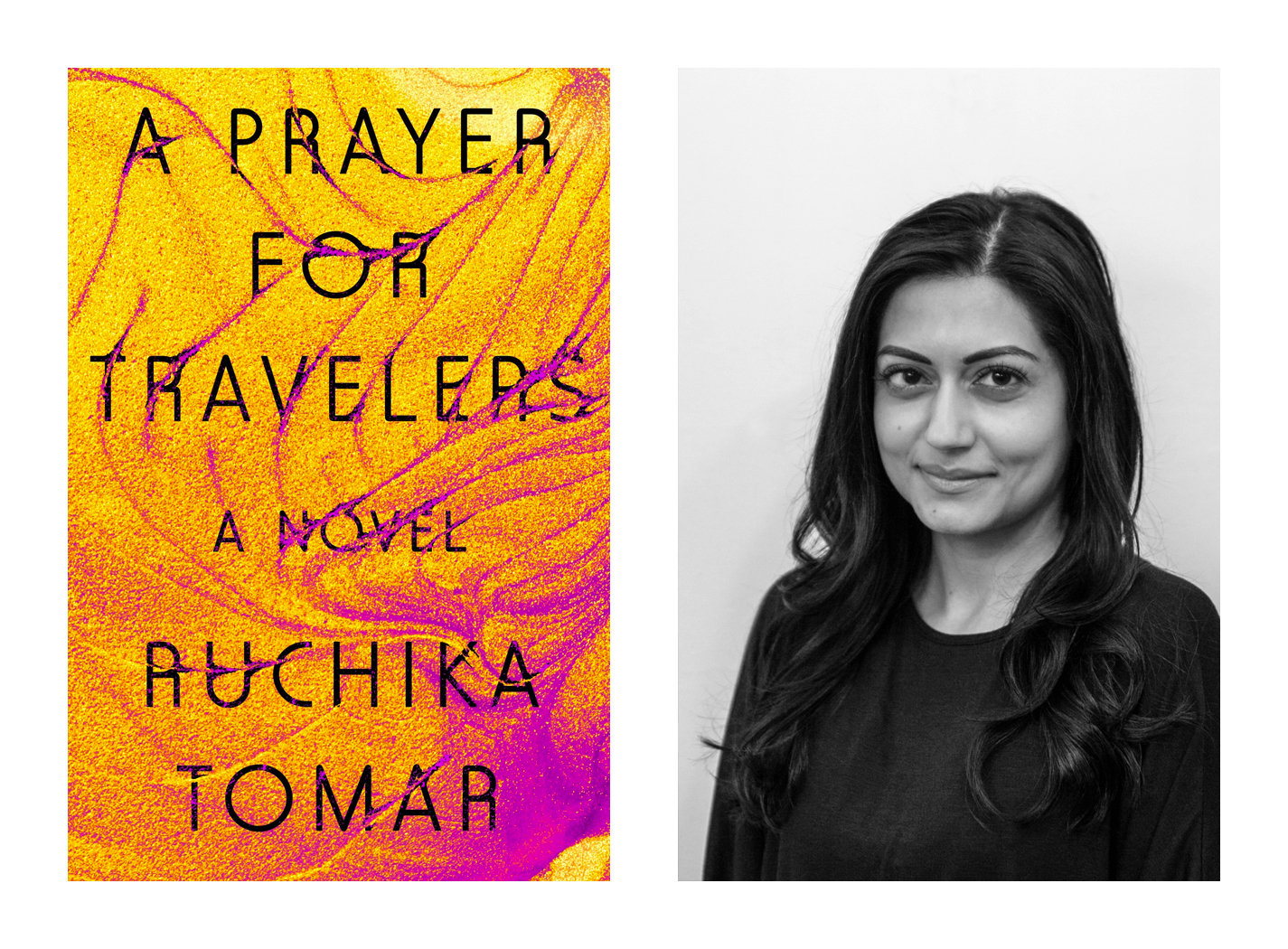

Ruchika Tomar’s debut novel “A Prayer for Travelers” is set in the fictional Pomoc, Nevada, a small, desolate town of working-class people in the middle of the desert, a landscape evocative of the author’s childhood spent in Southern California’s Inland Empire. The vivacity of Tomar’s prose renders this setting a character in its own right, its isolation and hostility creating the pervasive danger that transforms her characters’ lives. The narrator Cale is a reserved, book-loving girl on the cusp of adulthood whose quiet life is thrown into turmoil by the impending loss of the two people she holds dearest — her grandfather Lamb, who raised her alone and who is dying of lung cancer, and the charismatic and mysterious Penny, her newfound best friend who disappears one night without a trace.

This book has the classic intrigue of a missing-girl mystery and the heart of a bildungsroman, yet the way it intersects many threads of different identities makes it a highly unique and timely story. It’s about the female experience and trauma, people of color in the American West, non-traditional family structures and friendships with the strength of familial bonds, failure and apathy in the law enforcement and individuals taking justice into their own hands. Tomar treats each of these aspects of the story with sincerity, clarity and wisdom which make “A Prayer for Travelers” a critical read and mark her as a powerful new voice in literary fiction.

Though Cale and Penny were acquaintances throughout their childhood spent in the same small town, their close bond begins to build when Cale takes a job working in the same diner as Penny. It’s the kind of place frequented only by a handful of locals and truckers passing through, and the extensive downtime in that shared close space gives Cale and Penny a chance to form a peculiar kind of intimacy. Tomar cites this dynamic as the seed of her idea for the book: “I think female friendship, especially in a place like that, is really interesting, because you’re not only friends, but you’re at this point in your life where you rely on each other for a lot. You’re both kind of becoming who you’ll be, and you’re learning from each other what you want that to be.”

Cale, who has up until now only been truly devoted to her grandfather Lamb, begins to open herself up to Penny as shared rides home shift seamlessly into the girls spending time together outside of the diner. The girls become each other’s companions and guardians in a sense, but as Cale learns about the shady ways that Penny is making extra cash in hopes of escaping their prospectless town, she is brought into increasingly dangerous situations. In the seclusion of the desert, the risks that men, drugs and violence pose to the young women are particularly heightened. These shared traumatic experiences deepen the interdependency between the two girls, but ultimately separate them when Penny disappears one night after a deeply harrowing incident, leaving Cale alone to search for her. Many of these moments are inspired by Tomar’s own experiences as an adolescent in the Inland Empire and the trouble she would get into with girlfriends driving through the desert and sneaking into casinos in a place where there was so little infrastructure and so little else to do. “I remember a lot of those moments growing up, being in places where if I screamed, nobody would really pay attention. It was just by luck or guardian angels in some of those instances where I got out.”

Tomar’s compelling treatment of Penny and Lamb’s non-traditional family dynamic in this novel is equally inspired by her own experiences with family and relationships. “I’m a child of immigrants, a child of divorce … I’ve always had a complex relationship with family, and I think a lot of my friends do as well. I think the secret and the truth is that nobody’s family is perfect, very few people have the traditional two parents and white picket fence.” Tomar noted that her years living in New York City after college helped her find a community of people who were searching for a new kind of family. “That’s really the story of New York. Everyone there ran away from who they were. It’s like a city of orphans, which is why it’s so special. It feels like it’s a city of seekers, because everyone is always looking for some meaning or some interest, and they’re willing to go explore art or culture to try to find it. I think that’s also one reason why relationships can be so strong among people who don’t necessarily have traditional family systems themselves.”

“A Prayer for Travelers” displays beautiful craftsmanship on a sentence-by-sentence level, and I found that Tomar’s skillful sentence work and deft character descriptions shined through particularly in her expressions of the domestic relationship between Cale and Lamb.

“I was in the habit of regularly inventorying Lamb: his occasional restlessness, his aches and sprains, the accumulative gray peppering his hair, the smoker’s cough that seemed to exist alongside him in perpetuity, as Lamb-like as his green cans of shaving cream and back cotton socks sold five-for-ten at the drugstore on Main….

The room was warm and foggy and there was a vague foreboding in the air, like a slow and dangerous animal had broken into the house and was even now moving up the stairs. I strained to hear Lamb’s familiar downstairs sounds: the scrape of a chair pushed back, a cup being placed on a counter, the opening and closing of the icebox when he stole a slice of cheese.”

Passages like this one put on radiant display Tomar’s understanding of the unspoken rhythms that those we live with add to our lives, the quiet stability we depend on without ever necessarily stopping to take stock of it — all through the motions of its sentences. “For me, sentence work and language is the most delicious part of writing for me, so I think that’s where I wanted to give my attention to. It feels good, and it feels like every sentence is an opportunity, and you don’t want to miss it.” On every page of her book, her careful word choice and breathtaking imagery leave not one stone unturned — every beat of this book resounds clearly in the reader’s mind.

One of the most masterfully portrayed, devastating scenes in this book, for its protagonist and for the reader, is a scene of sexual assault. Tomar, who is deeply invested in writing about women’s issues with stark honesty and verisimilitude, indicated it was one of her priorities in this book to write an assault scene that didn’t gloss over the details as many books have before. “I remember growing up and reading books where assault was happening, and it was kind of left in the blank space, where I was supposed to interpret what was happening and how it affected the women in the story, and that was something that I didn’t want to do. I feel like that perpetuates the experience of men not understanding how we feel — not that they care — and women not seeing themselves, their experience and their emotions represented.”

This scene and its reverberations throughout the rest of the novel resonate particularly in the way they accurately capture the particular swirl of emotions that often surround sexual violence for its survivors — guilt, shame, self-blaming. These emotions are never static, but always shifting, and Cale has to grapple with them anew each day. In Cale’s words after the event, “What I mean to say is, I have tried to find my blame in this many times, and though some days it seems to be everywhere, other days it’s difficult to locate the exact pieces, like a plane breaking apart over the ocean, wreckage strewn and lost.”

Tomar insists on showing the harsh realities of the world that women do live in, not the one we’d like to live in. “I remember my editor disagreeing with the moment of Cale blaming herself, because he was saying, well, we don’t want to blame sexual assault victims. And I said yeah, but we do, right? We blame ourselves. That’s literally all we do — have anxiety, have guilt and blame ourselves. That’s the recipe for being a woman…”

In Tomar’s treatment of Cale’s trauma, she focuses on the way Cale feels totally destabilized, suddenly hyper-aware of her body and the lengths some men will go to access it, the harm it can bring her just by its existence in this world. In Cale’s words, “I was sorely aware of everything between my legs, its impractical value.” She can no longer inhabit the world with the ease and peace of mind she once had, all due to the body she lives in and what she understands now can be done to it.

Tomar’s book portrays the female experience of trauma from a deeply embodied and gendered perspective, which is still something we don’t see nearly enough of in fiction, which historically was and continues to be a male-dominated space. “Even in modern day MFA programs or when I was going to school, you see your peers turning in a story about a man’s interiority being praised, and a woman doing the same and it being said, something’s missing here. You get that message both explicitly and implicitly, in terms of what stories are prized, and who the authors are of the moment … If women are praised, often they’re praised for stories where you couldn’t necessarily tell [they’re written by women], it’s not focused on women’s issues, or women are not being shown as being aware of their bodies or sexuality, or if they are, it’s through the male gaze.”

Tomar has seen this same marginalization of female-centric literature in the reception of her book. “I was pissed when this came out and I saw that it was listed under women’s fiction. It still happens, all the time. I guess my reaction to it was just that at a certain point, I gave up … I just felt like, this is who I am, this is what I’m interested in, it’s always what I’ve wanted to do so it kind of doesn’t matter. Some people are gonna get it, and some people aren’t. I just gave up with the idea that men were ever gonna read me, or that men were ever gonna think my writing was valuable. I don’t think a lot of men will ever consider me somebody that they would read.”

“A Prayer for Travelers” is a perfect example of “women’s fiction” that is serious literary fiction and vice versa, and though Tomar doubts she will have much male readership, I think this is exactly the kind of book men ought to read today. It provides a clear window and powerful insight into what the world is like when you inhabit a female body, especially after its boundaries have been transgressed. We discussed in Tomar’s ENGLISH 90 class the fact that women are buying the majority of fiction today, so our desire to see our stories represented by writers like Tomar has real power to determine what is published. Still, Tomar notes, women and minorities have a long way to go to achieving genuine representation in the literary world. “The CEOs of all the major publishers are still white men. Some of the companies are buying more books by women and by minorities, but sometimes it still feels like a token acknowledgement of what the marketplace is asking for, versus their actual investment in diversifying.”

The form of her novel informed by its intense, gendered content, Tomar uses a highly nonlinear narrative structure, which mirrors the messy and complicated journey of coming to understand the trauma we have experienced and the effects it has on us as we get older. The novel’s weaving timeline reflects the ways Tomar sees real women telling long stories to close friends, jumping ahead, looping back and moving around time freely, rather than being rigidly bound to a beginning, middle and end. “There’s the experience of trauma, and then there’s how you process it later, try to put it back together and try to make sense of it. And it’s not neat, it’s not always clear, it doesn’t always make sense. Healing is a journey, right? You don’t just understand everything that happened to you one day.” Tomar worked at a clinic for women with trauma and substance abuse problems when she was in her twenties, and observing the methods used by trauma experts there influenced her approach to structuring this novel. “[Trauma experts] don’t just talk about it — they try to get you to develop coping mechanisms. They weave their way to get to the point, because often people aren’t really ready when they first meet you to talk about the most horrible day of their life.”

In addition to giving the reader a true-to-life experience of coming to understand the inner life of a woman who has experienced trauma and loss, the structure of Tomar’s novel heightens the tension of the narrative, making for a gripping reading experience. She is able to keep the reader in suspense, frequently across multiple timelines, by cutting back and forth between scenes. She imbues each scene with a deeper significance as it comes unlodged from its place in an objective chronology, allowing it to be told where the narrator Cale sees fit.

You could say Tomar’s journey to where she is today, an award-winning author teaching at Stanford, was as much like a woven patchwork as the incredible first book she created along the way. The obstacles she overcame to become a professional writer demonstrate her incredible dedication to the craft. After studying English at UC Irvine in the area where she grew up, Tomar moved across the country to complete an MFA in fiction at Columbia University in New York City, an experience she loved every aspect of, except for the hefty price tag. Most saliently, her experience in New York gave her a new outlook on the value of art. “In my family, the way I was raised, we were not taught that art was even a thing you were allowed to think about … so [New York] was the first time in my life that art in general was taken seriously. I had never been in a place where, in a public setting, that many people were reading, or that many people were excited to go see the new show. That’s insanity to me or to anybody I grew up with.”

Over the course of a decade after finishing her MFA, Tomar worked various nine-to-five jobs in New York — in journalism, as a receptionist, as a personal assistant — all while working on her book at night and on the weekends.

“Each night I would come home from work or the gym, make dinner and sit in front of my computer, open [my writing] and try to work on it. And sometimes, it would just be literally a sentence, sometimes I would wake up and it would be 3 am, and I had fallen asleep at the computer and hadn’t done anything. But that was fine. I think just by opening the document, something subconsciously in my mind prioritized [the writing] and made me feel like I was still connected to it, even if I hadn’t made real progress in weeks.” Each weekend was spent working on drafts, as well as her couple weeks of vacation time a year. “I don’t think I took a real vacation in, like, eight years.” Only after working on the novel for close to a decade did Tomar receive several fellowships which allowed her the chunks of time she needed to focus solely on the book and finish it, which was not feasible on a regular working schedule.

Tomar cites the community of writers she met through her MFA, who continued to think of her as a writer and believe in her, as critical to motivating her through these years. “I was like, I’m just a receptionist, or whatever job I was working at the time. And [my friend] was like, no, you’re a receptionist who’s writing a novel, and I was like, am I though? It’d been about five years at that point, and I was like, I don’t know what I’m doing, I don’t know what the plot is. Maybe I’m just not a writer. And I just remember the look that my friend gave me, and she was like, no, you’re a writer. We went to graduate school together. I know who you are. And that sustained me, for however many years, because I really didn’t feel like a writer. I didn’t know what I was doing with the book. But if the people closest to me who I really trusted believed in me, then I could believe in myself.”

I still remember how, in the first week of the ENGLISH 90 workshop I did with Tomar, she drew a timeline on the board to give us some perspective on how much sheer time, how many decades, we would have to work on writing to get from where we were to publishable writers, to notable writers, to the timeless masters like Tomar’s favorite writer Vladimir Nabokov. And still, the later two levels no one can really count on reaching, as they demand a certain talent and lots of good fortune as well as crafted skill. When I asked Tomar what she had learned about writing in the decade she spent grappling with her first novel, she gave me that same tough-love answer: “I think there’s just one major thing, which is that thing that nobody ever wants to hear — it takes SO long. Just to get even a quarter as good as you want to be takes so fucking long … And it’s really hard to process because very early on, when you’ve taken one creative writing class, you already know the essentials — setting, plot, point of view. I know this, so I should get it, right? It feels like I understand all the working parts — why isn’t it perfect yet? And I can’t tell you why it takes that long. It just does.”

Tomar is open about the arduous, thankless nature of writing as a profession, and yet she practices it and teaches it with an intensity and diligence that shows the joy of the craft is rewarding enough in itself to keep her going. This intrinsic enjoyment of the exertion is perhaps the only way we can survive and sustain ourselves as writers or artists of any kind. “It can’t be your concern as a writer how people read you or what they get out of it. The experience of writing it has to be fulfilling enough, and whether it has a life of its own in the world is kind of up to the world, up to publishers, up to reviewers to get it or not.”

“A Prayer for Travelers” recently received the 2020 PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Fiction, one of the most prestigious awards in the U.S. for a first novel, with past winners including literary giants such as Marilynne Robinson, Jhumpa Lahiri and Stanford’s own Chang-Rae Lee. In 2016, Tomar was awarded a two-year Stegner Fellowship, during which she finished up “A Prayer for Travelers” and submitted it to publishers, and in 2018, she took on the position of Jones Lecturer, where she is now teaching workshops and working on a new novel about the occult. Tomar is thankfully in a place now that affords her much more of the necessary time and space to work on writing. When I asked her about her approach to the new book, she said, “I’m trying not to put that much pressure on myself right away. I understand that it’s going to be ugly for many years before I try to make it beautiful.”

It seems to me that this essential ingredient for making art that is beautiful — time — is exactly what our society, and its conventional expectations of concrete, monetizable productivity, is always telling us we don’t have. Individuals like Tomar, who have worked incredibly hard at their craft and shaped their lives around it in order to make the time it needs, are inspirations for all of us. Time is generally not just given to us for our passions, for the endeavors which demand much more time and thought than their products would indicate at first glance, but if there is something you love to do, whose labor is challenging but rewarding in itself, then that something deserves all the time you can make for it.

Contact Carly Taylor at carly505 ‘at’ stanford.edu.