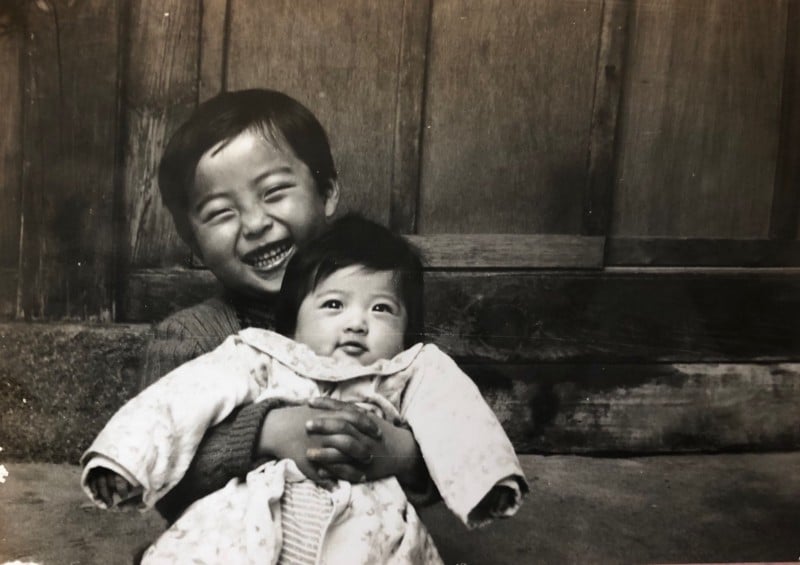

My grandmother tells me stories of a chicken she lived with throughout the Korean War. Amid the blood, guns and hunger of the 1950s, a seven-year-old Moon Hua Ji found a way to smile through chicken whispering: the tongue she used when playing with her favorite feathered friend.

“She always marched around the shack, pecking everyone’s faces,” she said. “Like this!” A 77-year-old Moon Hua Ji proceeded to bend her knees, flap her arms and pace around the dining table. I was dazed; it didn’t add up with any of the other details. For three years, life for my grandmother was living in a 10-square-foot hut, squished with nine other runaways, 240 kilometers away from her hometown, and no certainty of when she’d eat, go back home or die.

But a hen waddled into her shack one day, and she says there was a reason to wake up in the morning again. They danced, sang, cooed, chirped and giggled throughout the war—and for a confused little girl with no other friends, it was the only thing in the world that could save her.

“Despite what everyone else may say, I don’t think there’s anything more important than smiling. No matter how broken things may seem,” she said. I never asked about the war until a few months ago, fearing I’d bring up the pain she may have buried decades ago. But when I did, I was left with a most unusual answer. She grew up around unimaginable cruelty—and a mischievous chicken was what she held dearest.

Her daughter, my mother, is even more unusual. Since August of last year, my mother has had a proclivity for talking to plants. It started one morning when I was awakened by The Beatles playing from the living room speakers. I got out of my bed and dragged myself outside—cranky, confused and looking for an explanation.

There was no one. No human, that is; there was, instead, a potted basil plant, sitting in the middle of our living room, staring back at me. I think I stood off with the thing for 10 seconds before it registered. “Om-ma…?”

I heard tippy-taps from the storage room. My Om-ma, Korean for ‘mother,’ came prancing into the open space, performing a ballet routine. I asked, “What the hell are you doing?”

As she twirled, she said, “If you play nice music for the basil, it will feel happy and want to spread its arms out and dance, so it will grow better.” I sighed. “Look! It’s dancing too!” She had an unshakeable smile on her face, which I found just as unbelievable.

There was a disparity between my mother’s plant whispering and what was going on outside at that point of the year. We each have our ‘what if’s’ about 2020; for me, it was the people I never got to hug goodbye. I still find myself wondering how Gordon from English is doing in aviation school, or if Alan from the local food court has added any new dishes to his stall. You keep in touch with two or three, but there were so many people that I never got to look in the heart and say, I enjoyed being alive because of you. All the letting go that made me feel smaller than I ever have.

But my mother was also saying goodbye to her friends (we were moving to a new country), she also lived through COVID-19 and she found a way to smile. My grandmother lived through the darkest period of Korean history, and she found a way to smile. To love life in a time when the world seems unlovable: I think this kind of affection holds a unique felicity, because it would have been inconceivable had the world been perfect.

And isn’t that how we’ve conceived the rest of our greatest inventions? Hasn’t adversity been humanity’s wellspring for innovation? Consider our most primitive struggles: from our misunderstandings of one another, we created language. Loneliness birthed the musicians, dancers and painters of our time. And the most profound of all: had we never been starved by hatred, we would have never grown our capacities for love.

So I think back to that morning in August, and maybe there was something I missed. Since then my mother has grown a little garden in the living room; it’s the first place she goes to in the morning and the last place she looks at before going to bed. She was sitting on the floor one night, her temple against her knees, marveling at the olive tree. A tear hung at the edge of her eye. I asked her, “Why are you so interested in those plants?”

“Because—it’s exciting to watch something spread its arms,” she said. “These guys rely on me. And that makes me forget about money, or the pandemic, or anything else I have lost, even if it’s for a few moments a day. I sing for them, I put them in nice pots, I care for them—and the next day they’ve grown a little taller. Don’t you think it’s beautiful? That you can grow something, even when the world is on fire?”

And I realized what I want “loss” to mean to me. The idea that the death of something we held dear can give life to another: Isn’t that what nourishes hope through our nadirs? If we could embrace loss, as fully as our ever-broken hearts will allow, can you imagine what we could create?

Let gumption be what defines us, not adversity. I wish not for a future without suffering—but a future where suffering has made us more fearless and loving of life than we were yesteryear.

Contact The Daily’s The Grind section at thegrind ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.