Trigger warning: This article discusses rape.

Meg Remy’s experimental memoir “Begin by Telling” begins, literally, with a bang. A television has fallen on a young Remy. “Sesame Street is on top of me,” she writes. “The impact is profound. Though I suffer no physical injury, I can never forget what I saw.”

With that, the tone is set. “Begin by Telling” — out from Book*hug Press tomorrow — is a short, punchy, oft-graphic reckoning with personal trauma and abuse in an equally violent landscape of American culture. These traumas may not all be physical, but they are just as lasting: One “can never forget.” Through fragmented memories, anecdotes and reflections, Remy rebuilds the events of her past to see it more clearly.

But this particular investigation into the American female self is not a new one. Remy is the face of the band U.S. Girls, an experimental pop group based in Toronto, and since 2007 has produced seven studio albums that have garnered critical acclaim. Her most recent album, “Heavy Light,” was nominated for Alternative Album of the Year at the Juno Awards of 2021, and traces themes of capitalism, gender and childhood trauma — themes that are also present in each of Remy’s previous albums.

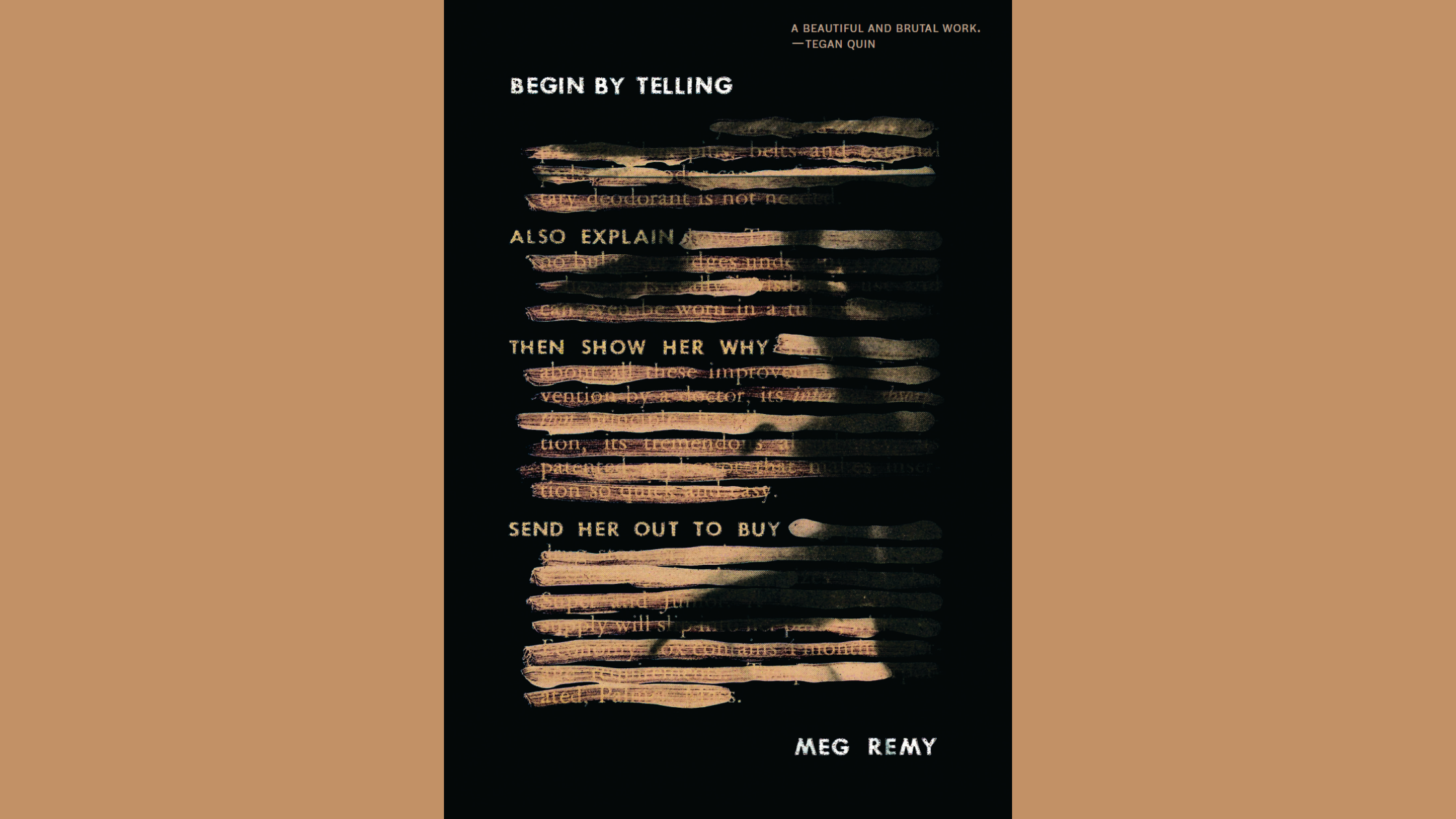

“Begin by Telling” contributes to Remy’s impressive oeuvre and allows her to continue reflecting on these themes through a different artistic form. Whereas music is a primarily aural medium, writing relies on the visual — which Remy utilizes to her advantage. “Begin by Telling” is a multimedia text object, and integrated into the memoir are original illustrations, footnotes and even a few short screenplays. We see that Remy’s experimentalism is not confined to music — her written work also strives to break down genre definitions and to challenge common conceptions of what should be.

There is a sense that, in place of what should be, Remy searches for what is, for truth. And in a history — personal or national — that is so fraught with violence and pain, the truth is a difficult thing to find. Events from her past mingle with major current events in the United States, and these things are united in that the traumas enacted by both are often buried under falsity, tactful omission or euphemism.

While simultaneously remembering a sex tape she made and a time when she was raped, Remy writes, “I Knew the evidence (blue Gap dress) had to be destroyed so I dissolved the tape in some way / now lost to time and / I didn’t tell anyone / I had been raped.” These artifacts — the material “evidence” — of sexual assault and deviance are both pushed away, covered up, forcibly forgotten. Society does not want to see these things. “For years of my adult life I said, When I used to have sex with … instead of When I was raped by…” Remy writes later. “How smart of me to be euphemistic!”

To search for some form of truth amidst these concealments, Remy turns inward: toward her own body. “Body just has a feeling,” she writes, and the footnote of which adds, “We do not see anything in the eye.” Throughout “Begin by Telling,” Remy often capitalizes the word “Know,” perhaps suggesting that this “knowing” is not from a cerebral consciousness, but instead from a deeper understanding that is felt rather than thought.

As “Begin by Telling” unfolds, we see Remy herself coming to terms with her past. Near the end of the book, a script between Remy and another person named Kassie shows some of the qualms Remy had as she was writing. Remy asks, “How do I tell a story I’ve never told out loud or even to myself? I mean, I’m not sure I can go there. It’s so painful. … Like, am I making all this up now just because I’m writing a book and I need material?”

To this, Kassie just responds: “No. You know what you experienced.”

Indeed, Remy does. And she knows that, while these experiences “will always hurt,” the pain “is temporary”: “Soon enough me and the United States of America will be dust.”

To recover and grow from trauma is a slow and long process. But Remy shows that there can be a path forward. One can listen to the knowledge of the body. One can remember things as they are, not as what others want them to be. And one can share such stories, with themselves and with others — can begin, simply, “by telling.”