Every summer, a group of undergraduates spend 10 weeks researching different aspects of earth science through the Stanford Earth Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SESUR), often making exciting discoveries and redefining their understanding of the field.

This summer, 19 of these students studied subjects in the earth science field — ranging from sustainability to geology — with Stanford professors and Ph.D. students.

During the program, students engaged in research both remotely and in person. Students commit 40 hours a week to their labs and are required to take a course or independent study on research preparation before joining.

Here’s how five students spent their summers studying the Earth.

Exploring community action to address sustainability issues

Earth systems major Bless Romo ’22 spent her summer working for the Social Ecology Lab remotely researching how communities collectively take action against environmental and sustainability issues.

Romo was interested in working in an interdisciplinary lab with a social science lens, while also learning about environmental issues such as climate change and sustainability.

Investigating collective environmental literacy — an individual’s understanding, skill and motivation to make globally responsible decisions — Romo spent her summer interviewing people to consider their relationships with the natural world.

“It’s not really deeply researched,” she said. “So one of the things we are trying to do is define it, but also to figure out how you can measure a community’s collective environmental literacy.”

Romo interviews environmental organizations in her hometown of Watsonville, Calif. to measure collective environmental literacy in each location by investigating communities’ attitudes towards sustainability. She studies how people use and share resources in their communities and noticed parallels between her interview findings and climate resilience.

“We all have our different lenses that we’re bringing to the table, so mine is climate resilience,” Romo said.

Carbon protection in agricultural soils

Gabby Barratt Heitmann ’24 joined the Fendorf Group — which examines farming practices and their impacts on carbon storage — to spend her summer on fieldwork and advance her interest in biogeochemistry. She also hoped this opportunity would help her decide whether to pursue the oceans or biosphere track in her earth systems major.

“A lot of the Fendorf Group research is more practical or more applied,” Heitmann said. “A lot of scientific research is very exploratory, and I liked that this seemed very grounded.”

The lab’s goal is to research how microbes can help contain carbon dioxide in the ground because soil used for agriculture is known to emit large amounts of the greenhouse gas. Heitmann looks for specific microbes called methanogens that can survive without oxygen in an effort to prove that small areas without oxygen exist in the soil.

Through Heitmann’s research, she discovered that there are methanogens in some soil, which contribute to degradation of organic matter.

“I think that’s an exciting thing about research is you’re like, ‘Oh my God, I’m discovering something groundbreaking today,’” Heitmann said.

Impact of climate change on Pacific invertebrates off the West Coast

Geological science major Christopher Noll ’23 spent the summer participating in the Historical Geobiology Research Group researching how invertebrates react to climate change.

While Noll originally had planned a research expedition to Friday Harbor Labs in the San Juan Islands, it was canceled because of the pandemic and he instead undertook a virtual research project with the research group to study how Pacific invertebrates on the West Coast would be impacted by climate change.

“This lab is focused on using our knowledge of the past to predict out into the future,” Noll said, “namely learning how perhaps climate change events in the past and its effects on marine organisms can be transferred over to our current climate change crisis.”

Through this research, Noll was fascinated by the complexity of the West Coast ecosystems and became more interested in the consequences of climate change.

Noll said his work has helped him realize how ecosystems would be impacted by climate change. Through his species assessments, he found that the West Coast contains over 600 species living in different regions and depths, but many won’t survive the changing climate conditions.

“From what we’ve seen so far, some of these species unfortunately don’t seem to perhaps be able to make it, considering the range and depth data,” Noll said.

Creating 3D models of coral reefs to analyze coral growth

Dakota Riemersma ’24, who plans to major in earth systems on the oceans and atmosphere track, spent the summer working remotely in the Dunbar Lab creating 3D models of coral reefs of the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean to prove that coral will regrow easier and faster after natural disasters, whereas it’s least likely to recover from human harm.

“I always knew that I wanted to do research, very early in my undergraduate career,” Riemersma said. He met earth systems professor Rob Dunbar, who recommended the program to him, as an instructor for an introductory seminar.

Using specialized software, Riemersma used thousands of pictures taken by divers in 2019 and 2021 and created three-dimensional models to evaluate the changes in physical properties between the two samples. He then aligns the two models and visually analyzes coral growth.

Riemersma’s experiences in the lab helped him learn the challenges in the research process: “You’ll make a lot of progress one week and not a lot of progress the next, and so that’s just all coming with experience.”

He added that he appreciated the opportunity to work directly for Dunbar.

“He’s made my Stanford experience so far,” Riemersma said.

Using geochemical tracers in sediment to determine basin formation

Planned earth systems major Bennie Hesser ’24 spent the summer working with the Sedimentary Research Group, which researches sediment and ocean basins.

“I have always been interested in geology and geologic processes,” Hesser said. He had originally planned to work as a lab technician in the winter quarter, but the pandemic prevented students from returning to campus.

Hesser focused his work on the rocks and soil on the Cerro Tenerife mountain in the southern Patagonian Andes, where there was once an ocean basin. He specifically works with samples deposited around 100 million years ago.

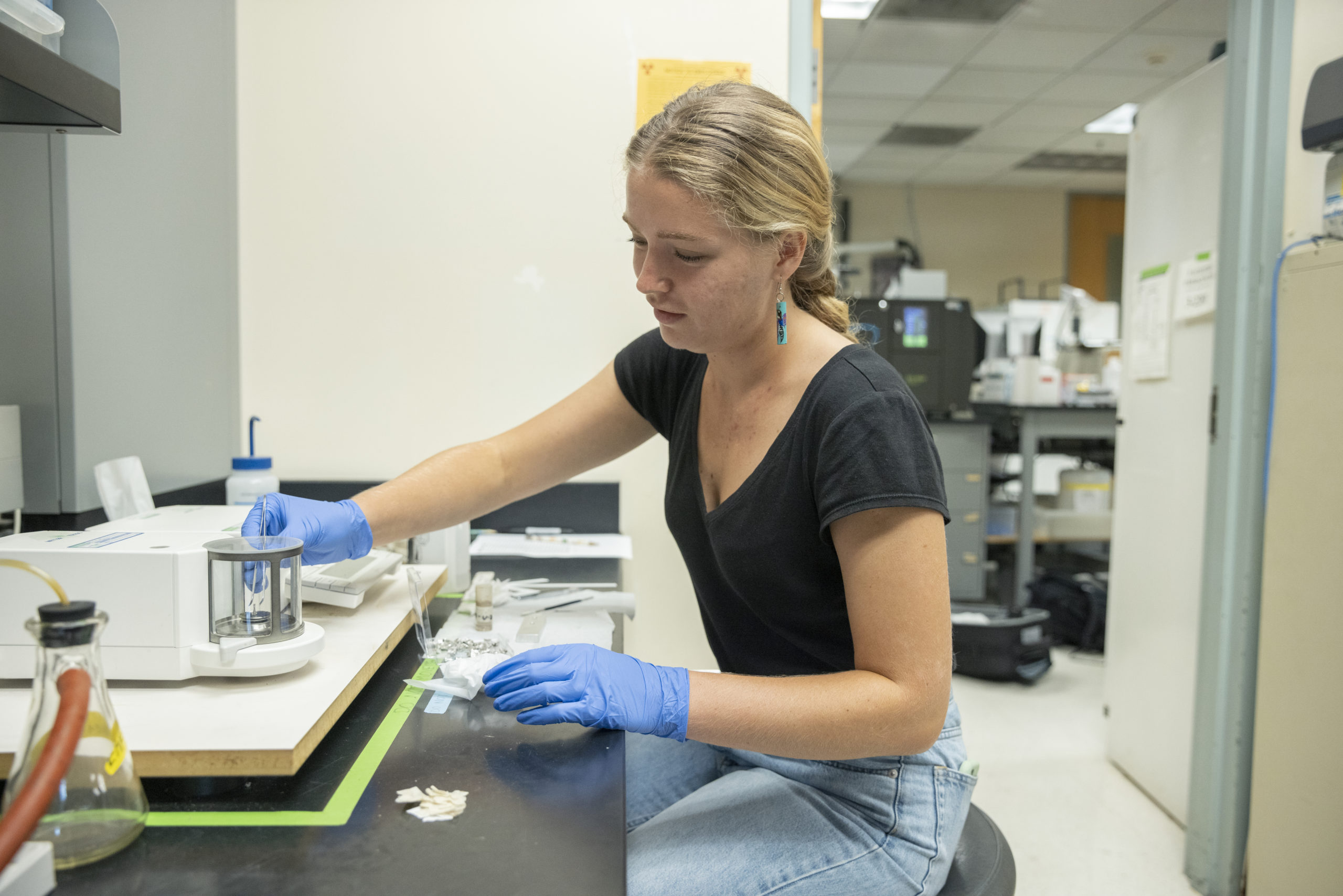

Hesser physically worked in the lab to cut, powder and analyze sediment samples. He looks for traces of certain chemicals, called geochemical tracers, to look at the different potential source rocks (where the sediment originated from) and help determine when the mountain building process occurred.

“My favorite part has just been getting to experience, hands-on and firsthand, the trials and errors and joys and discomforts of what real research is like,” Hesser said.