Stanford neuromodulation therapy (SNT), an experimental, accelerated version of magnetic pulse brain stimulation developed at Stanford, may provide a “revolutionary” treatment for severe depression, according to researchers at Stanford’s School of Medicine.

The researchers’ optimism comes on the heels of an Oct. 29 study in which the treatment was found to have induced remission in nearly 80% of participants. The study tested the efficacy of SNT on patients with long-term, moderate to severe depression who were also “treatment resistant,” meaning that they had unsuccessfully tried several other conventional forms of treatment. For many of these patients, SNT was the first treatment that successfully alleviated their depression in a significant, lasting way, researchers said.

“My brain has been rebooted,” said one patient treated with a modified, clinical adaptation of SNT who asked to remain anonymous due to concerns regarding the stigmatization of mental health treatment. “It’s like this cloud of depression has been lifted from me.”

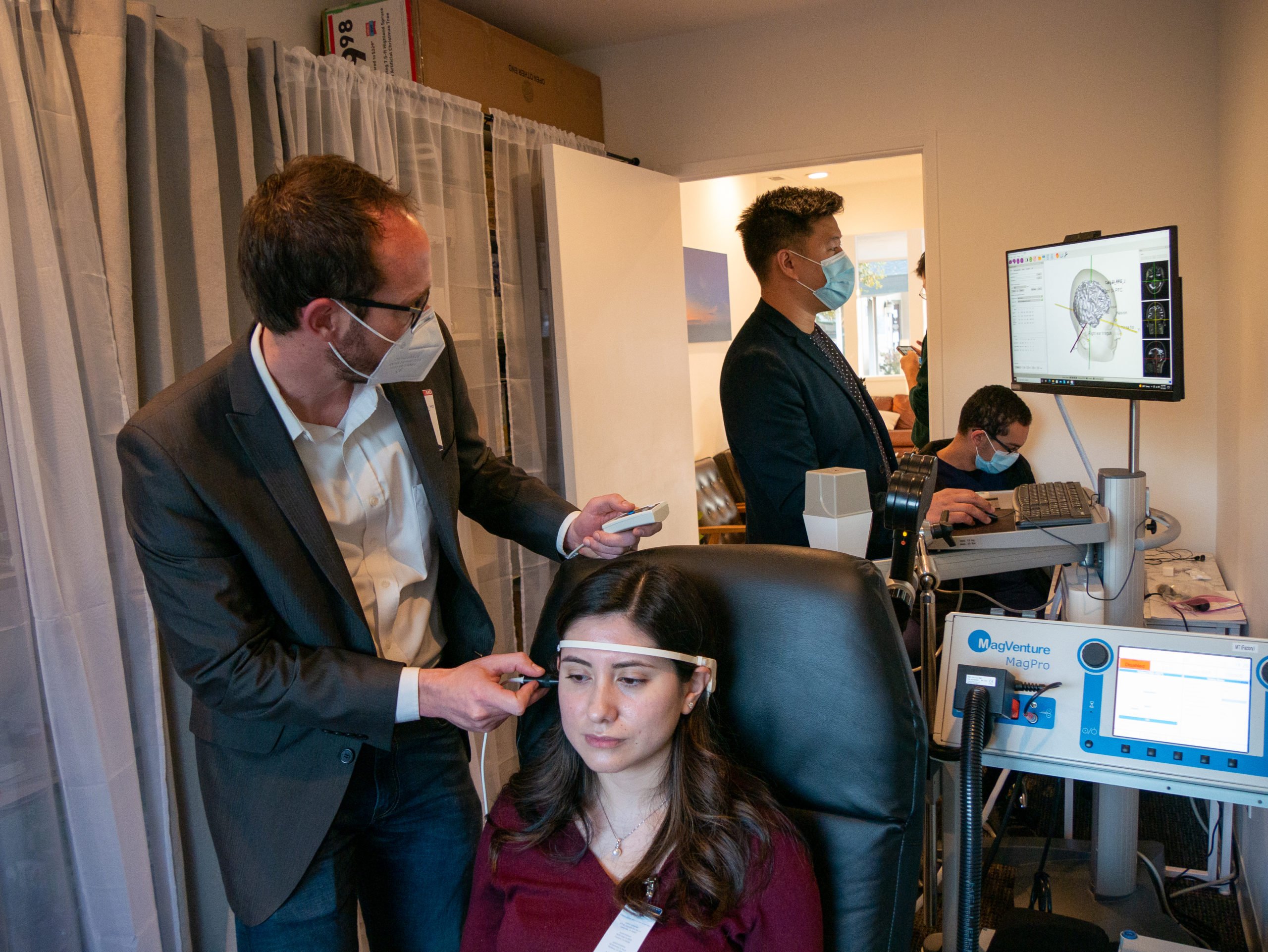

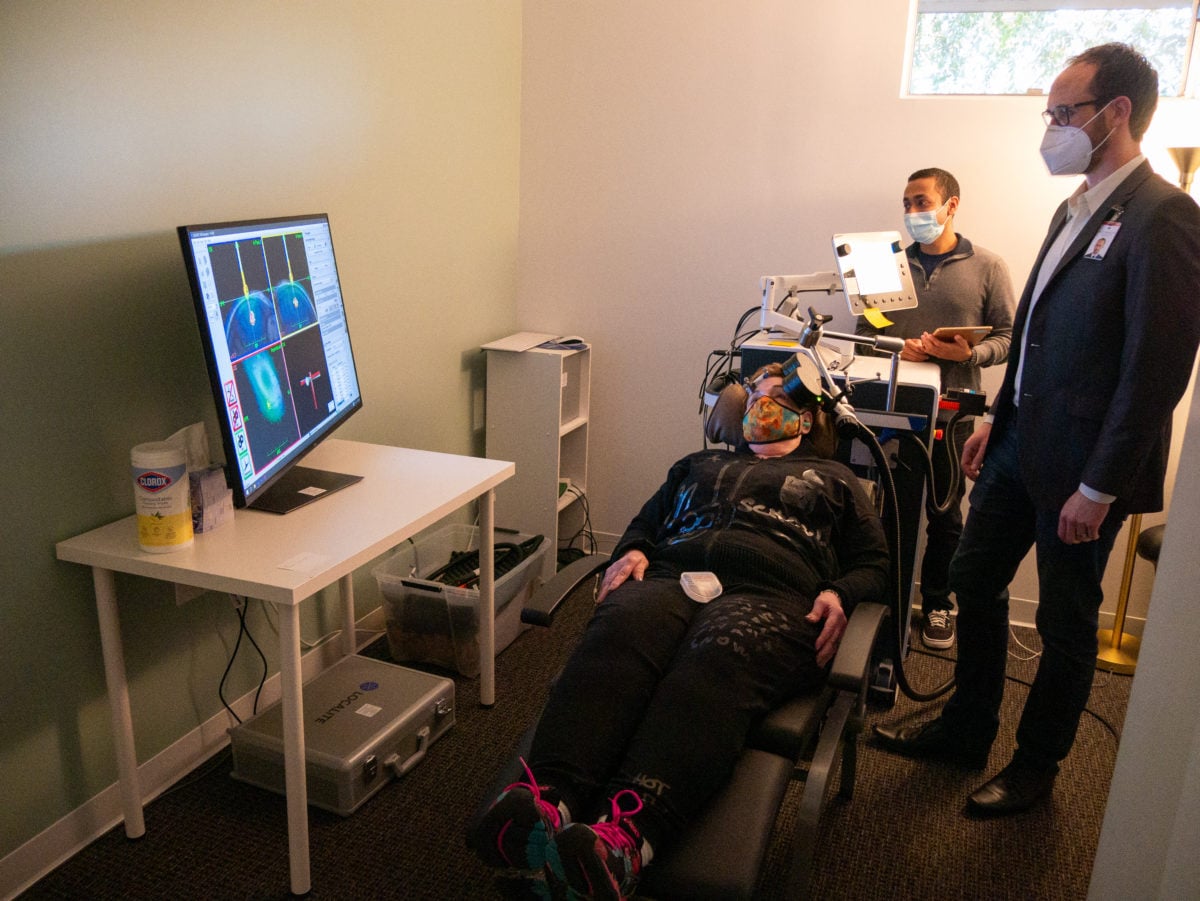

SNT is an adaptation of an already existing, noninvasive form of brain stimulation called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS delivers magnetic pulses to specific locations within the brain, activating neural circuits that show decreased activity during depressive episodes. According to researchers, while TMS has been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2008, its efficacy is limited, and it can take weeks for patients to show improvement.

SNT differs from conventional TMS in several key ways. First, SNT relies on functional neuroimaging to map out the brain, allowing researchers to pinpoint where to deliver magnetic pulses. Second, SNT deploys an especially efficient stimulation pattern that relies on fewer pulses to change neural circuits. Third — and most crucially — SNT dramatically increases the rate at which patients receive brain stimulation. While TMS involves one brain stimulation session per day for 36 weekdays, SNT requires only 10 stimulation sessions per day over a five-day period.

“There have been a lot of innovations in the TMS technology space,” said Nolan Williams, the lead investigator in the Oct. 29 study. “The question we tried to answer was, ‘how do we take what we now understand and reengineer TMS?’ And that’s what we did.”

Williams, who is the Director of the Stanford Brain Stimulation Lab and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, said that the research team plans to submit the data to the FDA, which has already deemed SNT a “breakthrough therapy.” Williams said that the timeline for the treatment’s deployment will depend on whether or not it receives FDA approval, although he is optimistic about its potential to treat a broad range of neurological disorders.

“One application [of SNT] is for people who are in psychiatric emergencies,” Williams said. “We’ve been doing this in obsessive compulsive disorder and borderline personality disorder. We think that this is a brain tool.”

SNT’s versatility makes it a much more compelling alternative to other treatments, said Kristin Raj, the co-chief of Stanford Mood Disorders and chief of the Stanford Bipolar Clinic. As one of the researchers in the study, Raj said that the study’s results demonstrate that SNT is far more effective than medication, which often produces diminishing returns after the first few doses. Moreover, SNT has none of the side effects that come with other popular treatments for depression like electroconvulsive shock therapy or ketamine therapy, which are still viewed as controversial.

“I’ve had many patients tell me how much hope it gives them to hear about SNT,” Raj said.

Still, despite overwhelmingly positive results, SNT is not a miracle cure.

Researchers have said that not all patients respond in the same way to the treatment — while some patients are still in remission years after being treated, others have reported relapse after only a few weeks.

Most individuals fall somewhere in the middle, said psychiatry and behavioral sciences professor Brandon Bentzley, who offered one hypothesis as to why responses to SNT might vary.

“What we’re doing in SNT is trying to move the brain from the default mode network, which is dominant during depression, to the central executive network,” Bentzley said, another researcher in the study. “My speculation is that different people have a different propensity to shift back to the default mode network.”

The question of how to extend the positive effects of SNT to all patients, Bentzley said, remains an active research focus.

David Carreon, another researcher for the study and a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, said that he has already adapted a modified version of SNT to his private practice, albeit without the functional neuroimaging techniques used in the Oct. 29 study. While the treatment is not as effective as the full version of SNT, it is still showing success in patients he said.

While SNT might offer hope for depression treatment, the stigma that hangs over mental health issues remains dangerous, according to the same patient who requested anonymity. The patient, who is a physician and was treated by Carreon, said that this stigma is especially prevalent within the healthcare industry, which takes an almost “militaristic” approach to denying the existence of mental health issues in its workforce.

“You would think that the healthcare system, since it’s so good at treating others, would be better at providing treatment for physicians,” the patient said. “But it’s more like, ‘Everyone else has problems, but we don’t.’”

Carreon said that many of his patients, including those who have gone into remission, have refused interviews with media outlets looking to report on SNT due to this stigma.

“People don’t want to be on national TV as the guy who was depressed,” Carreon said. “Even if it was in the past.”

The stigma surrounding mental health has real-world dangers; according to Enas Dakwar, a clinical psychologist at the Vaden Health Center, social stigma prevents many individuals from seeking support for mental health. This is exacerbated by the fact that many individuals with depression are high-functioning, Dakwar said, which can lead them to try to “fix” their depressive state on their own. Without proper support, these individuals often fail, “taking them deeper into the rabbit hole” of depression, Dakwar said.

This article has been updated to reflect that the treatment one of the patients received was a clinical adaptation of SNT and to correct the spelling of David Carreon’s name. The Daily regrets this error.