Afan Oromo, a native language of Ethiopia, is being taught at Stanford for the first time this fall as a part of the Stanford Language Center’s African and Middle Eastern Languages Program (AMELANG) offerings.

Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie banned Afan Oromo from being spoken, taught, or administratively used in the country in order to subdue the Oromo people and culture in 1941. After the ban was lifted in 1991, a push to give new life to the language began in and beyond Oromia and Ethiopia, led by native-born and diaspora Oromians, as well as non-Oromians. This push has now reached Stanford’s campus.

Among Stanford’s sizable East African student population, Saron Samuel ’25 along with Eban Ebssa ’25 told The Daily they sought to connect more with their heritage and put in a special language request last winter to get Afan Oromo added as a class. While their request was initially denied, they were told if they got at least one more interested student, the class might get funding. The special languages petition allows students to work with the university to add courses on less popularly taught languages.

Samuel sprang to action: “I sent the form in multiple group chats, reached out to people I knew would be interested in taking the class and posted on social media,” she said.

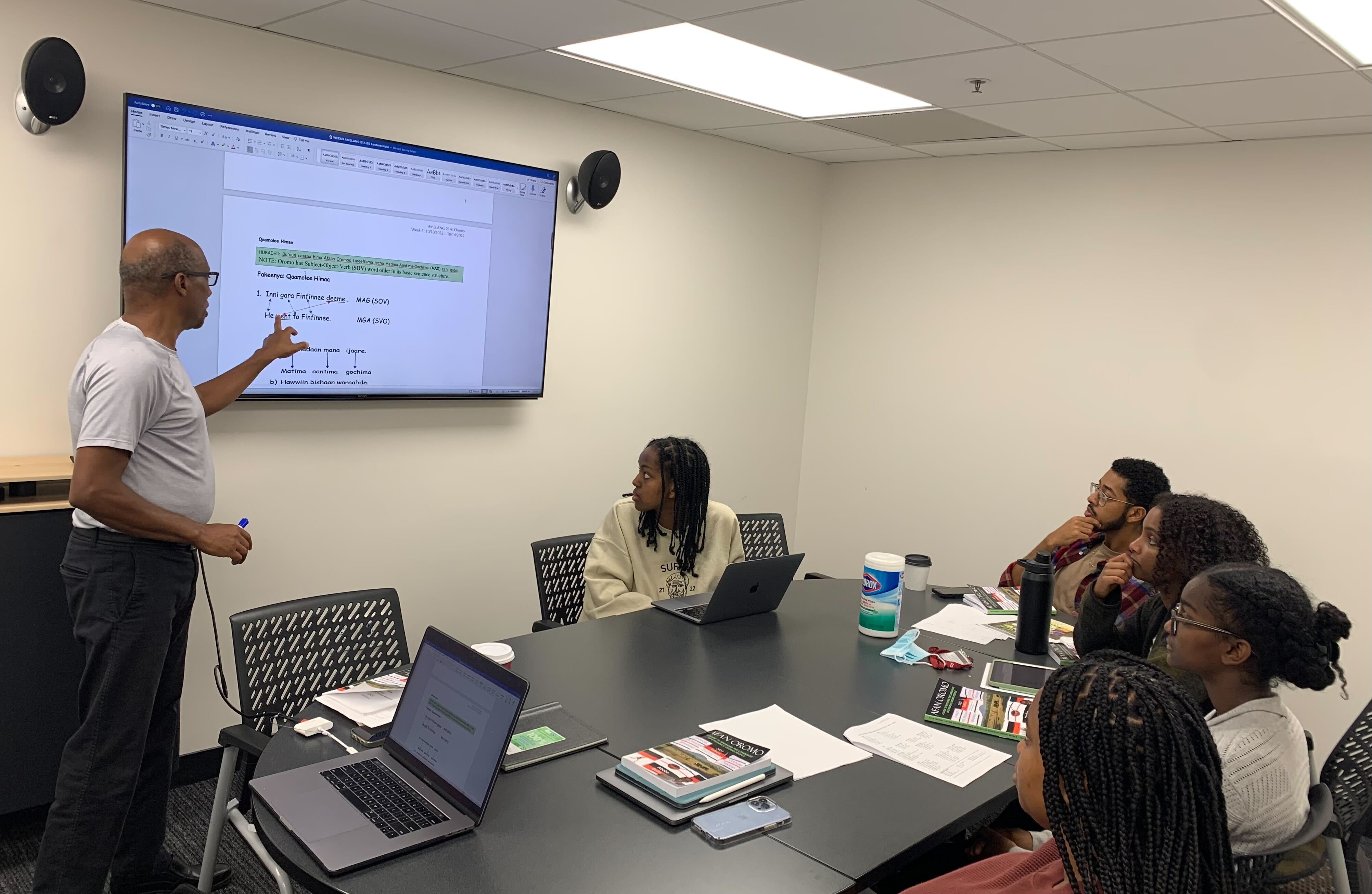

When the two had three more students commit to the class, the AMELANG Program expedited funding and hired a new lecturer, Afan Oromo teacher Belay Biratu, during the summer.

The University was able to add the course after a generous contribution from the Center for African Studies and in response to student requests, according to Coordinator of Stanford’s AMELANG Program, Khalil Barhoum. Afan Oromo is offered in a three-course sequence this year and will be the third Ethiopian language to be taught at Stanford, along with Amharic and Tigrinya.

Biratu told The Daily that he first learned the language secretly in the ’80s. He and other interested learners would meet in secret to explore the language. Although he was eventually caught teaching it to younger students and was punished severely for his actions, Biratu said he believes it was worthwhile, because he now gets to continue to teach the language and culture to those who seek it.

“In general, my view on teaching Afan Oromo is about doing justice to the culture. It is not against anyone, or any group. It is about doing justice to the people who are using this language as their mother tongue,” he said. “It is my passion and honest conviction that teaching language is doing justice to human culture.”

Biratu began this quarter’s class with an introduction of the sounds in Afan Oromo. Unlike English, Afan Oromo is a phonetic language and pronunciation is integral to its mastery, he said. He continues by teaching vocabulary, grammar and other foundational blocks of language-learning.

Biratu and his students consider themselves to be “pioneers who are paving the way at Stanford” for a greater appreciation and utilization of Afan Oromo.

Hawi Abraham ’24 said she has been petitioning the Languages Department to add Oromo since her freshman year, but the petition was never successful until now. Like Samuel and other students, she sought to learn the language to connect with her heritage and her family.

“My grandma only speaks Oromo, and not knowing the language was blocking me from this connection with her in many ways,” she said.

Abraham said she was never able to learn the language because of the lack of resources. She recalled a time when her Bay Area community tried to mount an effort to offer a course in the language, but there were no teachers or materials available.

“That’s why when I got into Stanford I knew this was one of my only chances to finally learn,” Abraham said.

Abraham said that due to the language’s half-a-century ban, there’s a palpable sense of enthusiasm and pride, as well as triumph, in the classroom. “Every time I walk into class, there’s a genuine excitement in the air to get it right and make our communities proud,” she said. “My parents never got the chance to learn Oromo in school, so every time I walk into class, I am so grateful for the opportunity that I am given, that many were not afforded.”

“Every time I learn something new, I call my family and share it with them,” she added. “I want to show them that the youth are not giving up on their culture, we’re fighting for it.”

“I am now learning Oromo and Amharic, and hopefully Tigrinya in the future,” Samuel said.

Today, the language is widely recognized, as the most spoken language in Ethiopia and the third most spoken language in Africa, and it is the lingua franca of the Oromo region. Because the ban ended only three decades ago, Ethiopian universities and institutions are now working to standardize and teach the language. Biratu hopes Stanford will join the effort.

Feyera Hirpa, a native Oromian and current chairman in the Northern California Oromo Community, said he is excited about the addition of the new class at Stanford.

“The community is just so proud because Afan Oromo is now being taught at Stanford, one of the world’s best universities,” Hirpa said. “I hope, and share this hope with many members of the community, that this is the beginning of something large.”

Biratu shared similar sentiments: “When this kind of thing happens, the Ethiopian community is so happy, it has been a dream come true,” he said. “We are just so happy for Stanford.”

A previous version of this article misspelled Hawi Abraham’s name and inaccurately attributed a statement to Saron Samuel. That statement has been removed. The Daily regrets this error.