Prominent journal Science issued retraction notices for two high-profile Marc Tessier-Lavigne papers today, the same day his tenure as Stanford’s 11th president officially ends. Tessier-Lavigne, who had previously defended the studies that have now been withdrawn, acknowledged that the research contained manipulated data in the notices.

This is the latest development in a months-long saga for Tessier-Lavigne, a renowned neuroscientist who has been beset by research misconduct allegations. A Stanford-sponsored investigation, prompted by a Daily article last November, found that Tessier-Lavigne had failed to correct the scientific record despite multiple opportunities over a 20-year period and presided over labs at three different institutions that produced a number of manipulated or fraudulent results. On July 19, the day these findings were released to the public, Tessier-Lavigne announced his resignation.

Tessier-Lavigne will stay on to continue research at Stanford, creating an unusual situation in which a newly designated tenured professor, the ex-president, must retract two studies on his first day. These studies represent only some of the concerns in Tessier-Lavigne’s body of research. Retraction processes for a different paper are believed to be underway at Cell and Tessier-Lavigne has said he will issue lengthy corrections to two Nature studies as well. Mark Filip, who led Stanford’s investigation, has said more investigations could come about.

In a farewell note to the community released Aug. 31, Tessier-Lavigne called his time at the helm of Stanford “the most fulfilling and rewarding experience of my professional career.” He was replaced at the end of the day by interim President Richard Saller, a former Dean of Humanities and Sciences who appointed Dean of Stanford Law School Jenny Martinez as provost earlier this month. Jerry Yang, chair of the Stanford board, said a search committee for a permanent successor would be appointed in the fall.

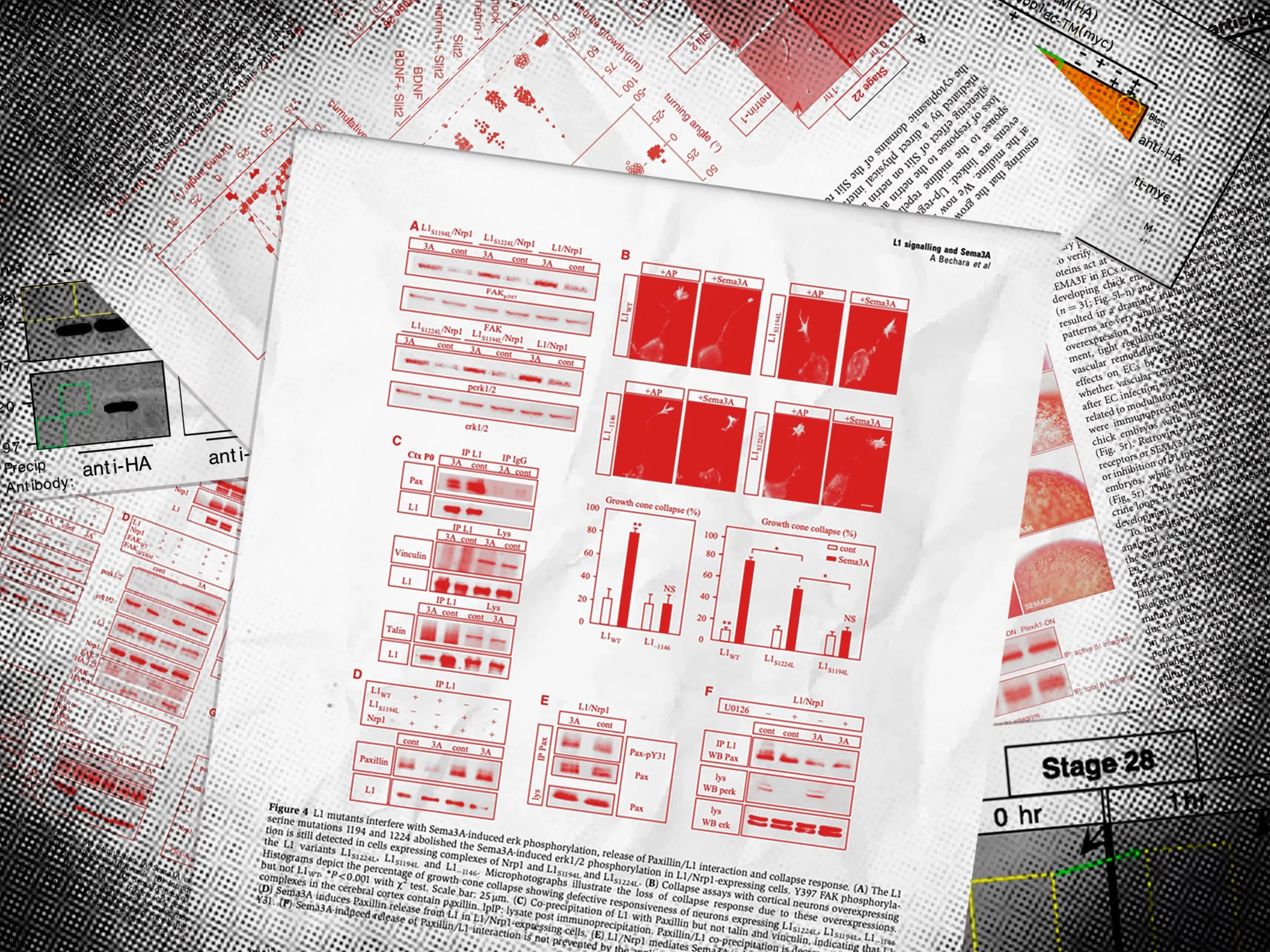

Together, the two papers retracted today, studies about development neurobiology that were published in the prestigious journal Science in 2001, accrued more than 650 citations. In a field where the median paper has seven citations, those numbers are significant and represent some of Tessier-Lavigne’s most cited work.

When The Daily originally asked Tessier-Lavigne questions about the manipulated research last November, Dee Mostofi, a Stanford spokesperson, responded on his behalf, arguing that the alteration did “not affect the data, results or interpretation of the papers.” This was widely contested by outside analysts, and Stanford’s investigation ultimately found that the papers contained “underlying manipulations that were performed and then attempted to be obscured.” The report did not find that Tessier-Lavigne manipulated any data himself or that he knew about the alterations at the time.

Tessier-Lavigne was made aware of specific allegations in the Science papers at least as early as 2015 and corresponded with Science about corrections. But when they weren’t published due to what the journal has called an error on its part, Tessier-Lavigne did not follow up. After The Daily’s report in November, the papers were issued Editorial Expressions of Concern, warning readers to be cautious while a final outcome was determined. As of today, the papers will be marked “RETRACTED” on Science’s website.

That the retractions would coincide with Tessier-Lavigne’s final day was a coincidence, said Holden Thorp, editor in chief of Science. The withdrawals had been scheduled for Aug. 25 before disagreements on wording caused a delay. Indeed, not all parties were on the same page about the notices — each retraction contains the caveat that “Author Elke Stein disagrees with the decision to retract the paper.”

Stein was the first author on both papers, meaning that she would typically have performed the majority of the work. Tessier-Lavigne was the corresponding author, meaning he supervised and assumed ultimate responsibility for the data in the paper. A retraction may be instigated by the authors of a paper, but it is the editor of a journal who has final discretion. According to Thorp, Tessier-Lavigne reached out the day before Stanford’s report was released to say he would retract the papers — an action Thorp said he would have taken regardless given the findings of the Stanford investigation.

On one of the papers, there were two other authors who agreed to the retraction; on the other, the only authors were Tessier-Lavigne and Stein. Neither Tessier-Lavigne nor Stein responded to a request for comment.

Stein first worked with Tessier-Lavigne during his time as a professor at the University of California San Francisco in the late nineties before relocating with him and his lab to Stanford in 2001 — the same year the retracted studies were published. According to one collaborator, some were already suspicious of Stein; it seemed “every experiment she does works perfectly, every time,” said the scientist, who requested anonymity for fear of professional repercussions from recounting their time working with Tessier-Lavigne. The colleague said that another lab working on netrin growth research around the time had failed to replicate parts of the studies now being retracted.

Around that time, concerns also began to emerge about the culture of Tessier-Lavigne’s lab, which the 2023 Stanford report said “tended to reward the ‘winners’ (that is, postdocs who could generate favorable results) and marginalize or diminish the ‘losers’ (that is, postdocs who were unable or struggled to generate such data).”

After Tessier-Lavigne went to Genentech, Stein moved to Yale, where she was a tenure-track professor. Still, she continued to interact with him. One principal investigator who ran a lab near Tessier-Lavigne at Genentech recalled that Stein would show up on occasion without explanation and introduce herself to others.

Stein did not get tenure at Yale, a university which requires those denied tenure to leave entirely. The circumstances are unclear, but Hank Greely, the Stanford Center for Law and the Biosciences director who offered Stein an unpaid fellowship in 2018, said he believed she had been denied tenure because “she had only published two papers in nine years.”

Scott Holley, now the chair of Yale’s Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology department, recalled her as “reclusive.” He said he had heard about problems in some of her work with Tessier-Lavigne in the mid-2000s, though not with any specificity.

After Stein came back to Stanford for her unpaid fellowship, Greely recalled trying to talk her out of applying for the associate provost for diversity position at the university, saying he did not think she was qualified. (Stein’s LinkedIn suggests that at the time she had not held a paying job for several years. It also prominently features one of the papers retracted today.) Following that conversation, Greely said he sent an email to Tessier-Lavigne, who replied that she “needed help.” Greely told The Daily that Tessier-Lavigne called Stein a “deeply troubled person.”

Since she left Stanford in 2019, it is unclear what Stein has been doing. Her LinkedIn, where she is still occasionally active, continues to list her as a fellow at a program that no longer exists. She was not a co-author on any of the other Tessier-Lavigne papers found to have contained manipulation of data.