The education most influential to Clarence B. Jones’s speechwriting for Martin Luther King Jr. happened not at Columbia or Boston University School of Law, but at The Juilliard School.

“When I hear words, I hear music,” he told students at a Monday event.

To commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the King Institute hosted a conversation with Jones, King’s speechwriter and attorney.

The event coincided with Jones’s 93rd birthday and followed the Institute’s first open house since the onset of the pandemic. From 2 to 4 p.m., attendees perused King’s original photos and writings and met with Lerone A. Martin, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Centennial Professor and associate professor of religious studies, who began his tenure as director of the Institute in January 2022.

Jones, who drafted the iconic “I Have a Dream” address and delivered the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” previously served as a scholar-in-residence for the Institute. In this role, he helped conduct research and organize volumes for the Papers Project, an initiative to publish “a comprehensive collection” of King’s writings, according to the website. Last year, Jones published his memoir, “The Last of the Lions: An African American Journey in Memoir.”

Monday’s conversation — mediated by Martin — centered on Jones’ upbringing and how it shaped his role as speechwriter and attorney for King.

Born an only child in 1930s Philadelphia to domestic servants (his mother was a maid and cook, his father was a chauffeur), Jones graduated from New Jersey’s Palmyra High School in 1949 as the valedictorian of his class and earned a full ride scholarship to Columbia University.

According to Jones, however, it was his education at The Juilliard School during a high-school program that significantly shaped his work with King. As a speechwriter, he had an “audio-imprinted version” of King’s voice in his head — a phenomenon he attributes to his musician’s ear.

Other parts of Jones’ work with King tested his adaptability: The first speech he wrote — which he called his “baptism by fire” — involved studying admiralty law for days in preparation for remarks at the National Convention of the National Maritime Union.

Jones also recalled smuggling King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in bits and pieces: He would arrive at the jail with blank pieces of paper in his suit, then exit with pages covered in King’s writing. After six weeks, he finally read the letter.

“When I read the letter there, sitting outside his office, I said, ‘Oh my god.’ I couldn’t believe it,” he said.

Jones hadn’t planned to get involved in the first place. It was only after King swayed him with a particularly powerful sermon that he decided to relinquish his safer, more lucrative career in entertainment law.

King “took an actual poem — Langston Hughes’ ‘Mother to Son’ — he took that poem, only he changed the words to it,” Jones said. “He made my mother the actor in the poem … He makes my mother like the woman washing down the stairs. And when he did that, I started crying, because I had a picture of my mother [in my head].”

Attendee Albert Hughes found this anecdote particularly touching.

“We only know what we hear about people, but everyone’s also still human,” he said. “We usually see leaders as great people and put them at that high esteem, but don’t realize that they’re human too and they have doubts too.”

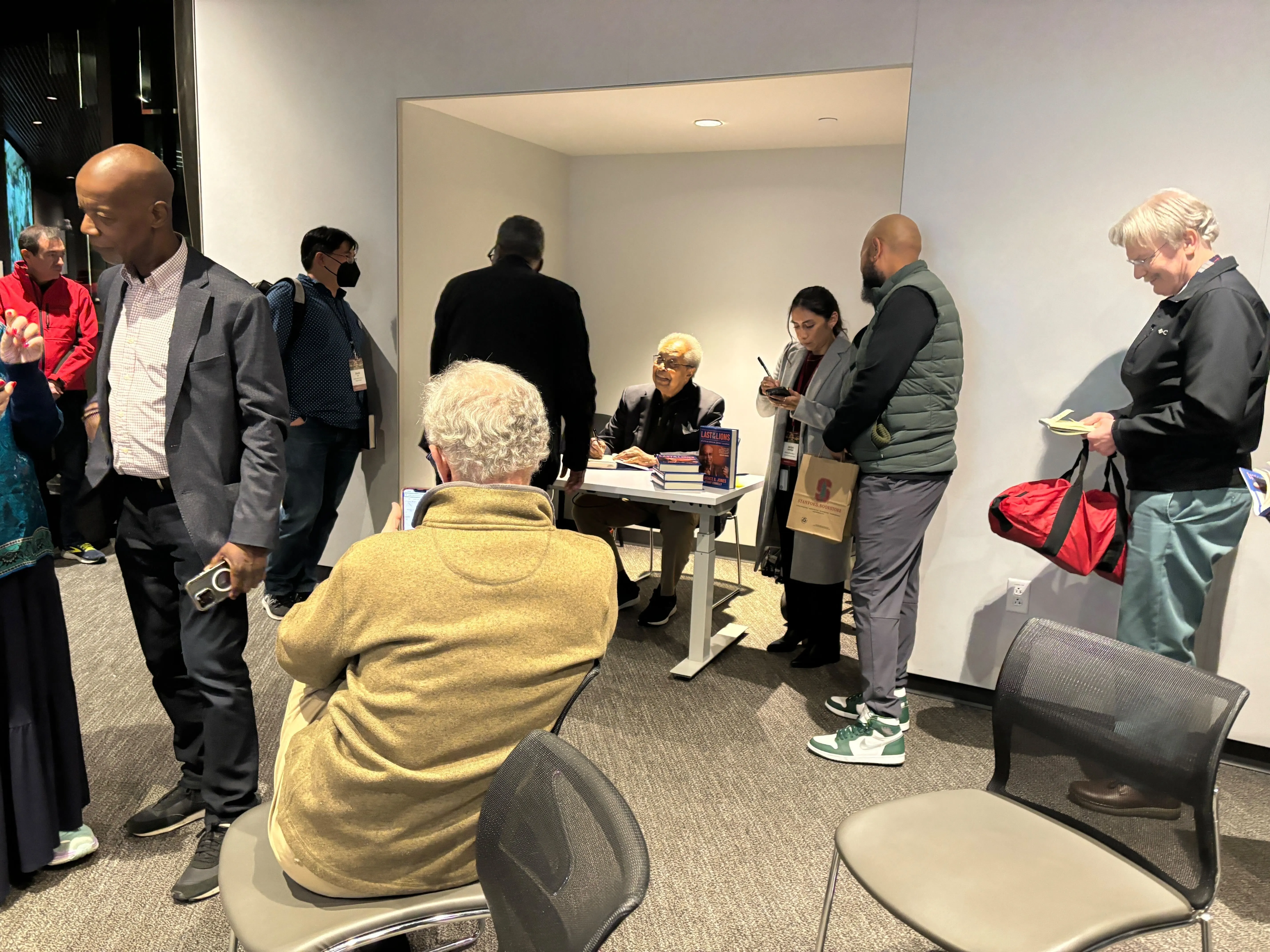

Following the conversation, participants lined up to sign “The Last of the Lions,” published in March 2023. The book is a departure from Jones’ previous work and proved “very hard” to put together, Jones told The Daily.

“This memoir was very painful to write,” he said. “I had to do a lot of self-editing; I had to make a balance of those things which I could comfortably disclose and write about.”

Some of this pain came through in the conversation. While Jones lamented that “never, ever, ever, have I seen or will there be another Martin King,” he added that there’s hope for student activists today if they abandon counterproductive habits.

“Put down the goddamn cell phone — read, read, read,” he said. “People don’t read anymore. You’ve got to read.”

Institute Administrative Director Regina Covington noted that through listening to the conversation and reading “The Last of the Lions,” community members had forged as close a relationship with King as possible.

“People talk about living history — that was a moment,” Covington said. “That was the closest you’re going to get to Martin Luther King right now, that degree of separation.”