In the dorm room, two girls sat cautiously apart on the bed. They were, at a moment’s glance, the spitting image of each other, but if one were to take a closer look they might have noticed that the one on the left looked a bit more frozen, a bit more perfect. She was something akin to a sculpture, but sculptures belonged on pedestals, while this one was, on a twin-sized bed, a bit less than human but close enough to touch.

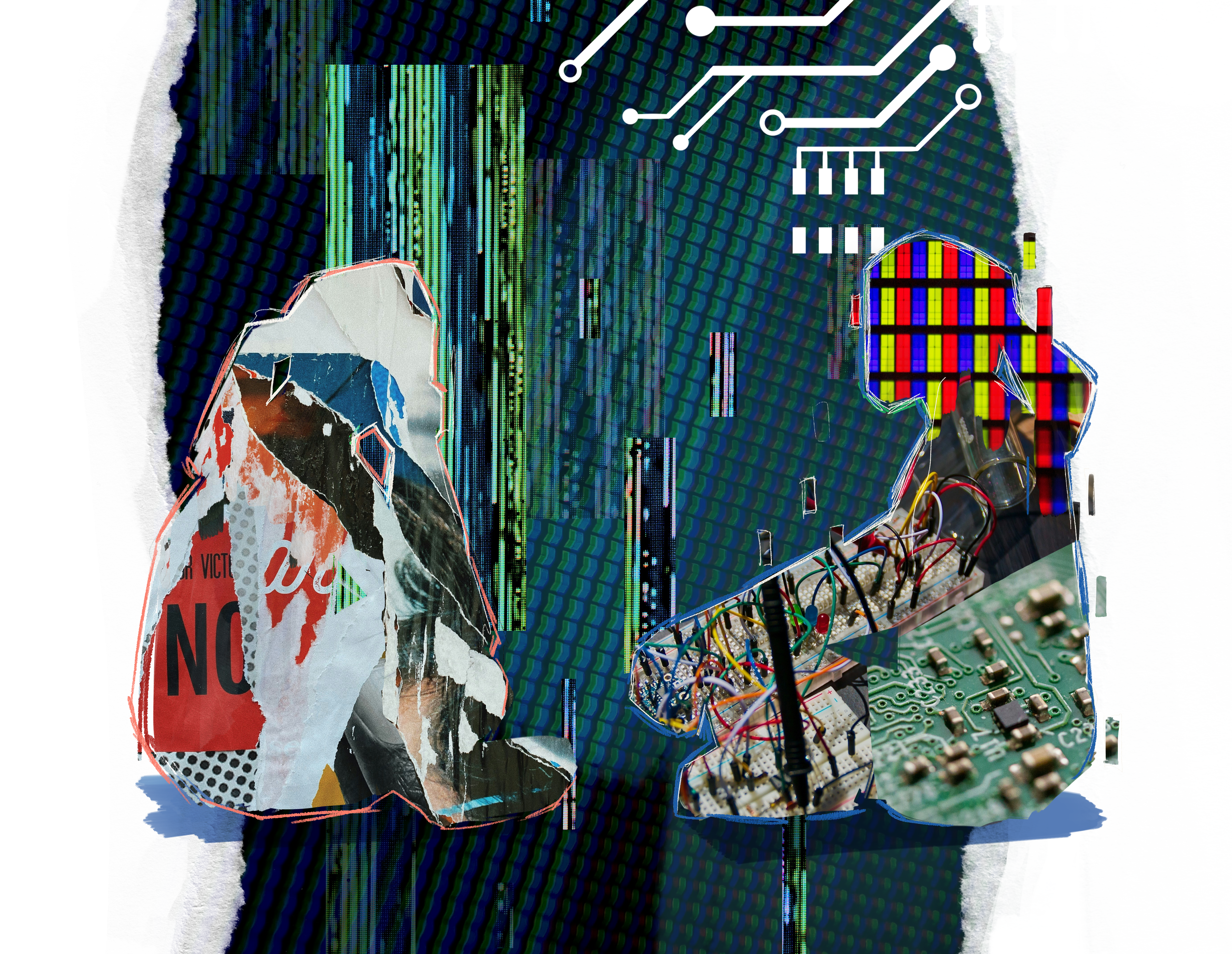

The other girl did not touch. She fidgeted with her hands instead. They were calloused and laced with thin scars from these recent weeks of wringing together all her possessions into the shape of herself, which coalesced into the person before her.

She was too tired to be proud. The days before had been spent stealing disassembling computers for parts instead of going to class, all to fashion a robotic version of herself on which to unload her burdens.

Making doppelgängers was a family craft, according to her mother, who had, before her first wedding day, pasted together a replica of herself out of napkins and cutlery and broken plates she scrounged from the restaurant at which she worked. The drive to do so arrived by pure instinct. In crafting its heart — this, her mother had said, was the most important part — she put in her ring, her old school uniform, a crinkled rose. In order to create the resemblance, you had to sacrifice something of your own — but not too much. Her mother had never explained what “too much” was.

When the time came, her mother had left her twin at the wedding ceremony, wrapped her belongings in a towel sack, and fled. Her husband didn’t notice until he leaned in for the kiss and his lips came away with the bitter tang of blood. He had cut his lip on glass.

At that, the illusion of his wife fell apart — quite literally, as the careful balance of silverware and glass shards came crashing down on the other side of the altar. That was the catch: the doppelgängers never lasted long. But by that point, her mother was far gone.

Perhaps running away from one’s problems was also part of the generational package. The girl had naively thought she could do better. That’s why she made it to university — to do better. Instead of knowing in the art of table setting and balancing plates on one hand, technology was her area of expertise. What happened? She couldn’t do better. It ended up being too much. The work, the social pressures, the act of living in her body. Too much.

So she gathered all of it— report cards, love letters, childhood stuffed animals — and built a heart around it. Then a body around the heart. Then limbs around the body. The overwrought metal began to take the shape of her. But she was sure to make this new version better. Slightly thinner, slightly faster, equipped with the solving skills of a supercomputer. The more alive it looked, the more she felt she could absorb some of it for herself.

When it awoke, it stared blankly into her eyes, the two of them unmoving on the bed. She got up. The robot got up too, and for a moment she worried she had gotten the calculations wrong, that she had done nothing more than copied and pasted herself on a metal mold and was cursed to live in double for the rest of her life. The both of them failures, unable to exist within the bounds of who they were.

“You’re going to go to classes. There should be instructions in your system,” the girl told the robot. “It will just be for a few days at most, enough for me to get my work done.”

The words hung in the air uncomfortably, the robot’s eyes perfect and calculating. The girl thought about her unread messages, her unsent emails, the patchwork of a Google Calendar that had been left fully ignored for the past few weeks. A second person was the solution. It had to be. The robot displayed no acknowledgement of this urgency, maintaining a subtly disinterested expression.

“Please respond,” the girl all but whispered. “I need to know I made your vocal chords right.”

The robot leaned back, flexing its fingers as if to confirm they worked. “Sure,” it replied, before grabbing the keys from the girl’s hand. “I’ll get going now.” It sounded exactly like her, but smoother, less hesitant. The girl blanched at the sound of it.

It was two hours before classes began, but the robot took leave swiftly, as if staying even a second longer in the room it was created in would be agonizing. As the jangling of keys grew fainter and fainter, a pang of loneliness struck her. It’s what she asked for, she reminded herself. She just needed a bit of time to get better.

So the girl lied down on her bed and waited for the getting better to start.

Outside, the campus was alive, with bikers and pedestrians weaving through the road like ants. The robot put one foot in front of the other, following the straight lines of its commands as other people rushed about. Its internal programming put an outsized focus on places and assignments, lectures and readings — nothing about interacting with the people surrounding it, which it found a far more fascinating prospect. Was it a window into what the girl had prioritized in her past quarter here, or was she just hiding her social life from the robot on purpose? It couldn’t be sure, but it felt the need to do it all — to absorb a bit of livelihood from the students it was walking past.

It felt a tap on its shoulder and turned around, coming face to face with a familiar student around its height with a look of surprised recognition on her face.

“Isa!” the student exclaimed. “It’s been so long since I’ve seen you!”

Yes. Isabelle. That’s the girl’s name. The robot reached into its reserves and pulled out a memory. One of Isa and Emmy together in the library. Isa was already treading water at that point, barely putting on the pretense of a put together human being. Emmy, on the other hand, was talking about her hangout with a group of people Isa didn’t know. She presumably had her work done or didn’t care — either state being wholly out of reach. Perhaps that was Isa’s breaking point — the robot could only guess. It needed to be friends with this girl, it decided just then. It had no rulebook for human interaction, but it did have a pumping heart of diary entries and high school polaroids. That would be enough.

It smiled. “I’m glad I ran into you, Emmy. How have you been?”

Isa was still collapsed on the bed when the robot arrived home that night. She lifted her head when her counterpart walked in, revealing watery eyes. Papers were strewn across her desk, still untouched. “I can’t do it,” she garbled. “But I thought I could. I really did.”

The robot felt sorry for her. Then again, it supposed it rather liked having Isa’s life. The robot was better at it too — it had succeeded in getting an invitation to an event in the span of an afternoon together.

“I’m going fountain hopping with friends. You should come,” Emmy had said casually. They were in Emmy’s room. The robot was worried she’d notice something was off about it, or ask it about Isa’s life. She didn’t. She talked a lot about her myriad of going-ons, and the robot listened. The invitation, therefore, was out of left field.

“You’ve never invited me to anything before,” the robot pointed out. Isa’s memories had nothing of the sort.

“Really?” The subtle undertone of disbelief in Emmy’s tone made the robot feel reassured, somehow. It had been forgotten, not disliked. “It’s just that you seem different now. Less distant.” Emmy smiled just then, a beautiful, knowing smile, and the robot felt a little singing in its heart that it supposed was what it felt like to be human.

It wanted to share this feeling with Isa, seeing her in that state. Maybe it would be a shared celebratory moment. “I’m going to go hang out with Emmy and her friends,” the robot said.

Isa sat up with alarming quickness. She looked dismayed. “You…”

Suddenly, Isa’s disheveled hair and trembling hands started coming into full focus. The sight of her seemed desperately pathetic, just then. Fading from the world, clinging onto a fading sense of personhood — it suddenly looked a little repulsive. As it turned around, Isa reached out. “Wait. Wait, no. Stay here. I’m going to go. I want to —”

“She wanted me,” her double said. Then it shut the door.

The robot approached the fountain in the middle of the roundabout as the moon shone overhead. The others were already there, Emmy and other girls like her, looking ethereal under the lamp lights. They were smiling and laughing at each other, with no incompetencies to hide and no secrets to keep.

“Join us!” Emmy exclaimed when she saw the robot approaching, before jumping into the pool like the rest of them. And there it was — that ideal now became an invitation, close enough to touch. The robot, Isa (she felt more deserving of the name now, all being said and done), was suddenly struck with the notion that perhaps it wasn’t so impossible for her to become something of a real girl. That what was buried deep inside her was more than the rot that created her, the rot that was now hiding alone in her room.

With her hope in mind, she stepped into the pool.

The water blanketed her ankles, before slipping into the gaps within her plating and rushed up her veins. It was exhilarating until her feet went numb. She didn’t so much as feel her knees buckle underneath her as much as she suddenly felt her body fall. Despite hearing faint cries of concern nearby, she plastered an imitation of their smiles on her face. Unburdened and unapologetic — that’s who the true Isa was. Even when her body was failing her.

A panel on the sole of her foot came loose. With her lower half gone, she slammed into the water. She hoped the others didn’t notice. It is hard to tell if they had, with the water clogging her head. Then again, if they noticed, it meant they cared, and that wouldn’t be bad at all. Maybe it was actually what she wanted all along. As she sank steadily downwards, she comforted herself with that image of who she thought she ought to be — someone worthy of being loved.