This fall at Stanford, frosh have missed out on some of the most infamous all-campus parties of the quarter — EuroTrash, KAbo, White Lies — many of which form core first-year memories that my friends and I still fondly remember. A considerable reason for this recent University-led crackdown is to hold fraternities accountable for the number of transports — when students are hospitalized after drinking too much — that occur at the parties they host.

The University seems to hold the position that fraternities, and Greek life at large, ought to provide spaces for responsible social aggregation rather than alcoholic belligerence. However, by punishing the fraternities for transports, I believe the University is only addressing a small symptom of a larger disease. The real question that lies unaddressed here is: Why do so many students repeatedly get drunk beyond control at parties? At some point, whether institutionally or culturally, we have to come to terms with the harsh truth: some people enjoy blacking out. And further, I want to suggest that the frequent occurrence of transports at frat parties should not be viewed as a product of Greek life itself, but rather as a symptom of Stanford’s work culture at-large.

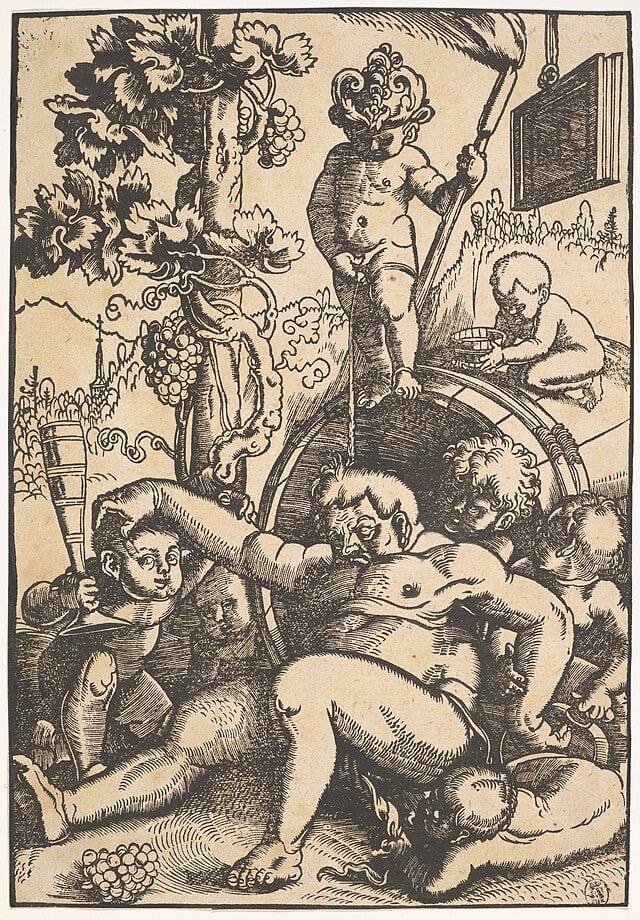

The lure of alcohol isn’t new to the 21st century. Even the Romans had their “bacchanales” — chaotic celebrations filled with music, wine and a temporary suspension of moral or social order (sound familiar?). These were done for Dionysus (aka Bacchus), the Greco-Roman god of ritual madness and, of course, wine. In “The Birth of Tragedy,” Nietzsche refers to the instinctual and irrational side of human nature as Dionysian, which he contrasts with the more Apollonian (rational and orderly) parts of man. It is useful to view our campus’s near-orgiastic frat parties as the Dionysian counterpart to the University’s Apollinian, reason-driven conduct — two equally necessary sides of human nature (is this perhaps why it is called Greek life?).

All of this to say, people have enjoyed ecstatic gatherings for millennia. But what compels even Stanford students to take it to the extreme and “black out?” Why is it not only fun but popular to inundate ourselves to the level of pure unconsciousness?

Stanford students work extremely hard to become leaders in society, but this high-achieving culture exacts a heavy toll for the average student. We see this acknowledged even by the University, which tells tales of “duck syndrome,” a phenomenon where everyone seems fine on the surface but keeps themselves afloat through a frantic (and at times, violent) work effort. It is a culture that demands incessant self-management. We must maximize productivity, maintain composure and a reputable image and be perfect in practically every way. How else can we get that job at Amazon?

What this ethic actually churns out is a lifestyle defined by an excessive policing of oneself. We limit our imperfections, abstaining from anger, idleness and especially irrationality. But suppression doesn’t make those impulses magically disappear. Rather, they become repressed and redirected toward the self, resulting in neurotic habits.

By “neurosis” here, I refer to the Freudian use of the word. A neurotic for Freud (“A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis”) consciously represses forbidden wishes, pushing them out of consciousness. A perfect example of a neurotic act, to me, is the picking and biting of cuticles — a habit I’ve found surprisingly prevalent at Stanford and among Gen Z, though it remains largely unacknowledged. Forbidding ourselves from showing overt aggression or anxiety, these negative impulses are repressed but not erased. Rather, they turn back onto us, showing up as concealed nervous habits like cuticle-biting. The picking of cuticles might as well be the paradigmatic image of the perfectionist Stanford student. An overt act of control, the anxious hand literally polices itself. It is in a similar light that we may view blacking out as a near-neurotic symptom of a larger cultural issue.

For a culture of people who, frankly, enjoy power and are near-maniacal control freaks, it is ironic that we have this urge to cede total control of our bodies and ourselves. To black out is to literally relinquish all control over oneself. It is a complete giving up of one’s rational processes, and can be understood as a total submission to unconscious instinct. It is interesting to note here how the suppression of instinct is, at least for Freud (“Civilization and its Discontents”), the foundation of civilization as we know it. We must repress certain violent, sexual or immoral urges to keep society afloat. However, as I’ve argued, these repressed drives nevertheless remain latently active. I’d argue that the desire to black out results from such repression.

Blacking out, in this sense, can be understood as a momentary revolt against culture. It is briefly entering into a world unburdened by consciousness, guilt or memory — all that sustains the rational world. Blacking out is the ultimate escape of all conscious control. Thus we may see that this desire is not completely a result of fraternities throwing parties, but rather the over-working perfectionism inherent in Stanford’s culture as a whole.

In sum: to prohibit frats from throwing parties might resolve a symptom, but it doesn’t address the larger disease. Though I do belong to a fraternity, I am not writing this article as an uncompromising advocate of fraternity culture at large. I just want to open up a new conversation. Perhaps, rather than literally repressing our outlets for escaping self-control, we need to start thinking of creative ways to accommodate the impulses of over-worked and over-policed students.

Correction: A previous version of this article referenced the Greeks rather than the Romans when discussing bacchanales.