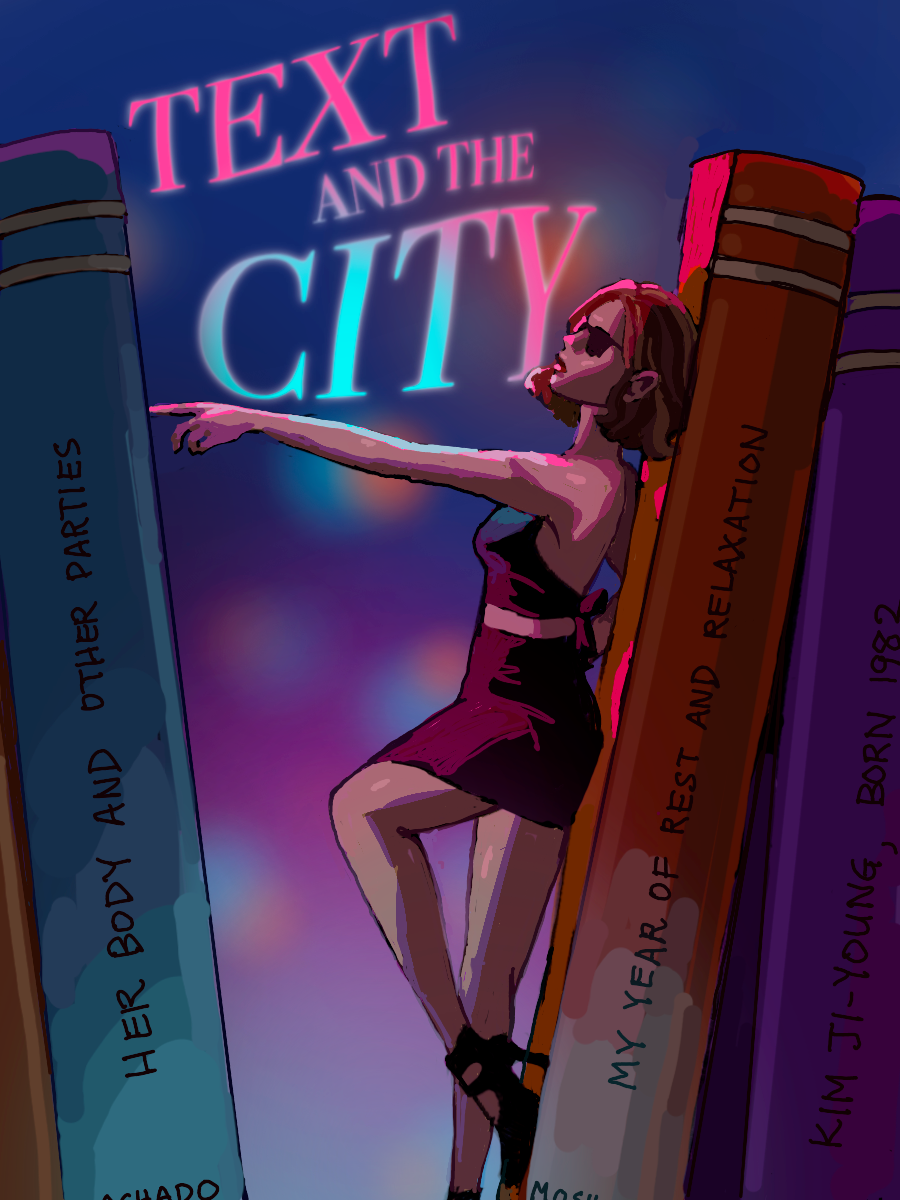

In “Text and the City,” Melisa Guleryuz ’27 reviews books through a lens of modern femininity.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.

Marjane (“Marji”) Satrapi’s “Persepolis” is a graphic novel that pairs stark black-and-white art with a voice so alive, so rebellious and so uncensored that you forget you’re reading about a revolution until you feel it happening under your skin.

In “Persepolis” — which, in a nod to Iran’s history, derives its title from the capital of the ancient Persian Empire — Satrapi tells the story of her childhood in Iran during the Islamic Revolution and her adolescence in Europe. She chronicles her life with the kind of clarity only a child — and then, a woman who has survived such things — can provide. Early in the book, young Satrapi announces, “I was born with religion,” a line that is humorous in its bluntness but heavy with reality. She proceeds to spend the rest of the memoir wrestling with the difficulty of having an identity handed to you before you know how to pronounce it.

What stands out most in “Persepolis” is how Satrapi depicts the collision of innocence and political upheaval. One page shows Satrapi dreaming of being a prophet. The next portrays executions and bombings. Yet another illustrates her bargaining for a Michael Jackson button even though “it was strictly forbidden,” Satrapi writes. The memoir never sanitizes childhood; instead, it honors how children pick up the pieces adults break. At one point, Satrapi says, “The revolution is like a bicycle. When the wheels don’t turn, it falls.” It’s the kind of metaphor you don’t forget, because it comes from a girl who is trying desperately to understand why her world keeps collapsing.

Satrapi’s feminism is loud, impulsive, contradictory and wonderfully human. Satrapi refuses to be the quiet, obedient daughter the new regime insists she become. When her school orders all girls to wear a veil, Satrapi says: “We didn’t really like to wear the veil, especially since we didn’t understand why we had to.” In her teenage years, when she buys Western clothes despite the risk, she tells us with pride that she feels “liberated,” even as Guardians of the Revolution scold her for her punk jacket. Satrapi shows how girlhood itself becomes an act of rebellion — that growing up with your own thoughts is threatening in a society where obedience is the preferred national sport.

But “Persepolis” is more than a story of oppression. One of the most powerful lines in the memoir comes from Satrapi’s grandmother, who tells her, “Always keep your dignity and be true to yourself.” It’s a message that becomes the backbone of the book, as Satrapi shows how difficult — and how essential — that instruction is. Her feminism is inherited, nurtured and relentless. Even the women around her who do conform, who stay silent or wary, radiate a quiet strength. Refreshingly, Satrapi treats them not as symbols but as people navigating impossible circumstances.

The memoir is also sharply and unexpectedly funny in the way truth often is. Satrapi recounts how she and her classmates mocked their teachers, how she declared at age six that she wanted to be “the last prophet” and how she marched around pretending to lead the revolution. Humor becomes a survival skill, a way to stay human when humanity is under threat. Reviewer Rachel Moulden wrote that Satrapi’s voice “makes you laugh right before it breaks your heart.” She’s exactly correct.

Then comes Satrapi’s departure from Iran for her own safety: Europe, loneliness, the confusion of being seen only as Iranian rather than as Marji. Here, the memoir shifts into a different tone. Satrapi begins to understand that freedom can be disorienting and that “sometimes you don’t know how strong you are until being strong is your only choice,” a line so striking, it is little wonder that it is often cited in reviews. Adolescent Satrapi is homesick, rebellious, depressed, self-destructive — and painfully honest about all of it. That honesty is what gives “Persepolis” its feminist core: it refuses to give us a sanitized heroine who triumphs through purity. Satrapi gives us a girl who is flawed, angry, brilliant and real.

By the time Satrapi says, “I finally understood that I was nothing but a Westerner in Iran, an Iranian in the West,” the memoir becomes not just a personal story but a universal one about the longing to belong, the impossibility of fitting neatly into categories, the work of constructing an identity from fragments.

“Persepolis” is not a tragedy, though it is full of heartbreak. It is not a political manifesto, though it critiques politics better than most manifestos do. It is, instead, a story about survival, the survival of humor, of girlhood, of truth, of resistance, of self. It is a reminder that becoming yourself is political in a world determined to tell you who you should be.

When the book ends and Satrapi walks through the airport, leaving her country behind, the only thing she hears is her mother fainting. Satrapi closes her memoir with a haunting phrase: “It was the last time I ever saw them.” And that final panel — simple, devastating — tells you everything you need to know about the cost of freedom. In “Persepolis,” Satrapi makes her defiance clear through both the written word and art. And in doing so, she gives every reader — especially every woman — permission to do the same.