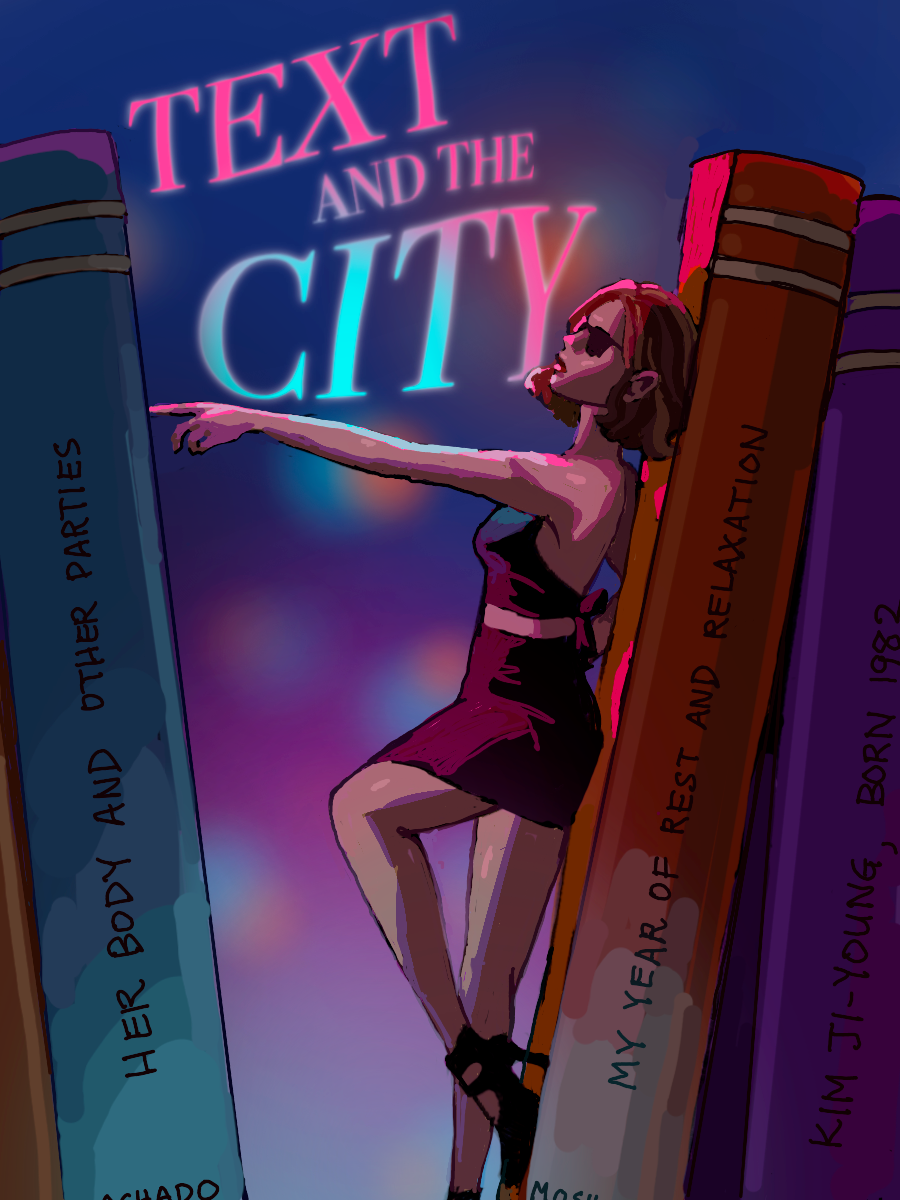

In “Text and the City,” Melisa Guleryuz ’27 reviews books through a lens of modern femininity.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.

In her 1996 novel “Hotel Iris,” Yōko Ogawa crafts the kind of reading experience that leaves readers unsettled rather than resolved. It lingers and creates discomfort. Reading it feels like watching someone silently disappear while everyone insists she is “fine.”

“Hotel Iris” follows Mari, a teenage girl who lives by the sea. Working in her mother’s hotel, Mari must navigate a world where words are slippery and desires are imbalanced. From the first lines of Ogawa’s book, “The desires of the human heart know no reason or rules,” readers can tell that Mari’s voice will be observant rather than assertive.

Mari’s relationship with her mother sets the tone for everything that follows. They are both caregivers and ciphers to each other: close yet distant, necessary but never truly intimate. Their dynamic lacks maternal or filial warmth; rather, it’s transactional and tinged with unspoken resentment. Mari’s mother seems almost jealous of her — harming Mari by deliberately brushing her hair roughly, even as she showers her in praise over her physical beauty. Mari does not belong anywhere. She is unwanted by her mother and forced to labor away at Hotel Iris until she is suddenly desired for the first time in her life. Mari does not seem to understand the meaning of being uncomfortable, since she’s spent her life with an overbearing mother who oversteps her boundaries and prioritizes her role as a hotel manager above motherhood.

At times, Mari reflects on the praise she receives from her mother, particularly how it feels internalized rather than appreciated. “In fact, the more she (her mother) tells me how pretty I am, the uglier I feel. To be honest, I have never once thought of myself as pretty,” she describes. This line is emblematic of Ogawa’s broader intent: feelings emerge as raw unfiltered experience, without the emotional padding most narratives give us.

The strange relationship that unfolds between Mari and a much older translator, who becomes fascinated with her — only deepens the meaning of the silence between Mari and her mother. At first blush, his words can sound caring: “I beg of you to go on living in this world I inhabit. I suppose you find this a rather ridiculous request, but to me it is of the utmost importance that you simply exist.” But as the story progresses, the line becomes more grotesque than gentle — a version of possession disguised as existential need as sexual boundaries are constantly being crossed.

Here, what stuck out to me was not the sexual boundary crossing itself, which the novel does romanticize, but instead the emotional tone. The demand from her mother and the translator is that Mari remain herself: shy, kind and selfless, rather than taking ownership of her own life. However, through this borderline-abusive relationship, she learns to dive deeper into her rather strange sexual desires to lose control. At the conclusion of Ogawa’s novel, Mari finally lets go of others’ expectations of her to bloom into herself, gaining autonomy for the first time in the novel.

By refusing narrative redemption, “Hotel Iris” makes the show a disturbing, yet compelling read. There is no arc of escape, no epiphany that solves everything. Viewed through a modern lens, particularly one attentive to power and femininity, the book feels magnetic. Mari’s mother is a woman defined by her role in the hotel, by her labor and silence. Mari herself learns a form of emotional containment that mirrors the structure of the hotel: rooms with thin walls and hidden desires subject to surveillance.

Ogawa also shows how hope — or the promise of it — can be thin and misleading. The translator’s narration, “Everything will work out. Don’t be afraid of breezes and scarves,” is offered as a seemingly gentle reassurance. But in context, this reference to scarves is frightening and tragic, as it refers to the translator’s dead wife. That very scarf was wrapped around her neck as it got caught in a subway door, choking her to death.

Ogawa’s prose is minimalist — every sentence feels deliberate, almost cool to the touch. Read “Hotel Iris,” and you’ll find a story that returns to you again and again, reminiscent of a melody that plays endlessly in your head.