Researchers from the Stanford School of Medicine have developed an antibody shown to be effective in treating a wide range of cancers. The antibody encourages the body’s immune system to attack cancerous cells and could help treat patients with advanced cases of the disease.

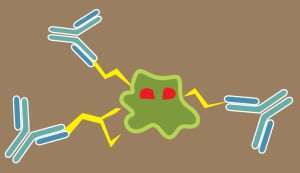

Irving Weissman M.D. ’65, a professor of pathology at the Stanford Medical School and the study’s lead author, noted that cancer cells often exhibit a “don’t eat me” signal caused by the CD47 protein, which stops the body’s immune system from attacking and destroying the cells.

Weissman first observed the expression of CD47 in blood stem cells, later noting its presence in leukemia stem and cancer cells, where the cancer is often more highly expressed.

“This study, which is pretty surprising, shows that [the signal] is present on every human cancer that we’ve tested,” Weissman said.

Researchers took malignant tumors from human patients and transplanted them into immune-deficient mice. After a period of time, the mice were treated with the antibody, which blocks the CD47 protein and allows the immune system to attack unshielded cancer cells.

The treatment was effective in all cases, reducing the spread of cancerous cells and often even ridding the mice of tumors altogether. Researchers tested the treatment on ovarian, breast, brain, pancreatic and colon cancers.

“The chances that the tumor cells can develop resistance in a way that we couldn’t overcome it are pretty low,” said Jens-Peter Volkmer, one of the study’s co-authors.

Researchers noted, however, that the antibody treatment may initially induce temporary, mild anemia in test subjects. The treatment often destroyed the mice’s oldest red blood cells — which also use CD47 to deter the body’s immune system — before affecting cancer cells.

The study later used drugs that increase red blood cell count to counter the anemia. Red blood cell count did not decrease with subsequent doses of the treatment.

The antibody treatment may also prove significant in treating other diseases, according to the researchers.

“We definitely think CD47 is involved in other forms of possibly auto-inflammatory diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, and we’re investigating all these different pathways…but a lot of that is preliminary right now,” said Stephen Willingham, another of the study’s co-authors.

As the treatment enters clinical trials — which will test the effect of the treatment and any possible toxicity on human patients with advanced cancers — Weissman and his team will conduct further testing with a group based in the United Kingdom.

“Because they have a national health plan and a single payer for the insurance, they only have to negotiate once,” Weissman explained.

The collaboration also grants researchers access to a greater pool of subjects, as significantly more cancer patients in the United Kingdom enter clinical trials compared to the United States. While there will be an “all-comers” clinical trial held at Stanford, the researchers said they anticipate a substantial delay before the trial becomes available.

The researchers noted that the treatment will likely be priced in a way that increases accessibility for patients without insurance or whose insurance does not cover the treatment. However, they added that the cost will depend in part on how much of the antibody would be needed to cure patients and whether other drugs are needed in combination with the antibody.

“It’s our intention to recommend setting a price that the greatest benefit will go to the most people, therefore it must be at a lower price,” Weissman said.

Treatments to be used in the clinical trials will be manufactured by the end of 2013, though Weissman expressed his desire to push manufacturers to accelerate production.

“What we’re doing now is what people usually do in a start-up company,” Weissman said. “We’re doing this with a batch of Stanford medical students, Ph.D. students, clinical fellows, post-doctoral fellows — and almost nobody is professional. So every step of the way, we’re training people, and I’m learning myself how you really do a clinical trial.”