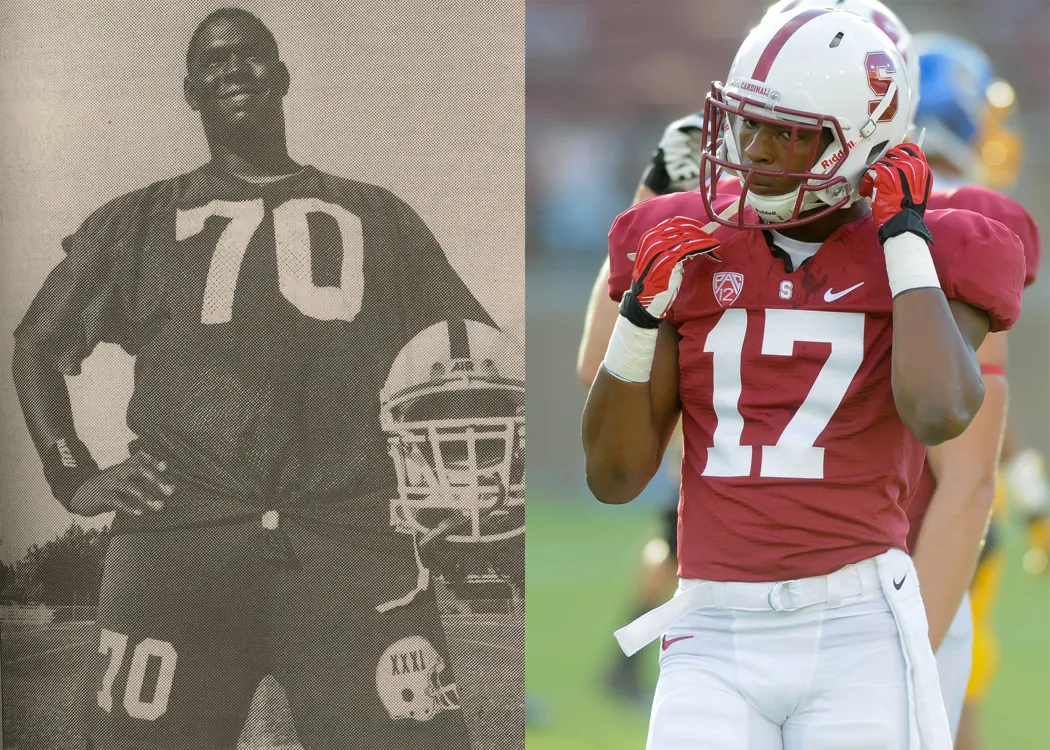

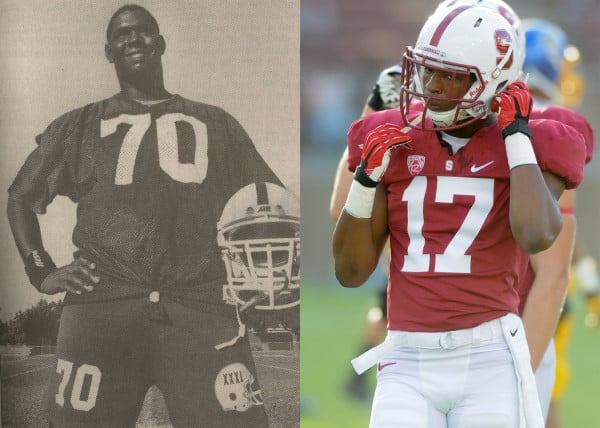

Bob and Kodi Whitfield share a last name, a passion for football and a school. The obvious similarities between father and son pretty much end there.

‘Big Bob’ was once a Pro-Bowl offensive lineman who spent 15 years as a terrorizing, 310-pound force in the National Football League. Kodi is a sure-handed, 188-pound receiver of the future who is still looking for his first collegiate catch.

But Bob and Kodi have something new in common: When they made plans to come to Stanford for the summer, neither had much say in the matter.

Bob still had to make good on a 20-year-old promise to his mother to earn his degree. After three years at Stanford, he left as the eighth pick in the 1992 NFL Draft, and went on to start consistently in his decade-and-a-half career in Atlanta, Jacksonville and New York before returning to complete his final classes.

“You can’t miss Big Bob driving across campus,” joked a former Stanford teammate, Cardinal head coach David Shaw, in August. “I wish he had some eligibility left.”

Kodi, meanwhile, had caught the eye of Pac-12 coaches as one of the 20 best receivers playing high school football. Bob was the Cardinal’s top recruiter.

“I told him, ‘You have no choice, you’re going to Stanford,’” Bob said.

Of course, Kodi already had his sights set on the Farm — “Parents can be persuasive and all that,” Bob said, “but it’s better when the kids realize it for themselves and grasp it” — but his dad’s strong advice exemplifies an unmistakable trend in Cardinal recruiting.

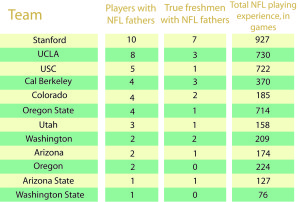

Stanford now has 10 sons of former NFL players on its roster, accounting for a combined 927 games of pro football experience. Both are the highest figures for any Pac-12 team; the rest of the conference averages about three players per squad. And of those 10 Stanford players with NFL pedigrees, seven are freshmen and members of the best recruiting class in school history.

Recruiting coordinator Mike Sanford remembers when, not too long ago, Stanford’s academic prowess was its only real shot at attracting young football prospects. Parents have always been hooked on the school first, he says. But as the Cardinal established itself as a football powerhouse by winning 23 games over the last two seasons, it began to attract more prominent recruits — and more prominent parents.

For safety Ed Reynolds and running back Ricky Seale, all it took to choose Stanford was their NFL fathers’ education-first mindset — plus a little bit of advice late in the game.

“I couldn’t go anywhere else,” Reynolds said. “The only thing [my dad] said was, ‘When you pick a school, pick a school where you’re going to have a decent quarterback for the next couple years.’ It just happened to be Andrew Luck.”

Luck started the trend in more ways than one; his father, Oliver, was a pro quarterback with the Houston Oilers before parenting one of the best passers in college football history.

Sanford insists that his staff doesn’t specifically recruit based off an NFL bloodline, instead giving the answer that has come to define Stanford recruiting: “We look for the best football players that also happen to be the best students in the country.” For whatever reason, many NFL players’ sons fit the bill perfectly, and for whatever reason, many of them have ended up at Stanford.

***

Kodi Whitfield’s path to the Farm is perhaps the easiest to trace. He was around for all but two of Bob’s 15 pro seasons and remembers “falling in love with the sport” through his dad’s career.

Still, Bob downplays the role his own success has played in his son’s development. If anything, he had to make sure Kodi wouldn’t become complacent.

“The sport is so demanding that, for all my greatness, that’s not going to make him that great,” Bob said. “[I remember] saying to him, ‘Yo, it’s not an easy life. Kid, you’ve got to go earn it, you’ve got to work hard to be a good player and it’s just not going to be given to you, regardless of your last name or your lineage.’”

The last name Whitfield carries special weight at Stanford, where Bob was twice named an All-American lineman blocking for ‘Touchdown Tommy’ Vardell and playing alongside Shaw, then a wide receiver. Just a year after Bob’s retirement from pro football, Kodi began looking into Stanford when it memorably upset 41-point favorite USC in 2007.

The Cardinal staff looked into Kodi as well, and he eliminated any suspense by committing to Stanford in June 2011, more than six months before many top prospects in his class would decide.

“We just had to reaffirm how much we wanted him here,” Sanford said. “We don’t want you here because of your dad, we don’t want you here because of the significance of having another Whitfield here. We want Kodi Whitfield here — Kodi himself.”

But when Kodi walked onto the Stanford campus, he was hardly the most hyped freshman around. That somewhat unfortunate distinction fell to running back Barry Sanders, whose father of the same name is known as one of the best pro backs of all time. In 10 seasons with the Detroit Lions, the elder Sanders never failed to make a Pro Bowl team and compiled 15,269 yards, the third-highest career total in NFL history.

Barry J., as he likes to be called to distinguish himself from his father, began to make a name for himself in high school, helping Oklahoma’s Heritage Hall win two state titles and earning a listing by ESPN as the ninth-best tailback in the country.

By late 2011 he was choosing between Stanford and Oklahoma State, just as the two schools were preparing to meet in the Fiesta Bowl. Many in Sanders’ home state thought he would choose the Cowboys, who played just an hour away from his high school and also happened to be his father’s alma mater. On the other hand, academics had long been a priority in the Sanders family.

“[His parents] were so tremendous in just guiding him along the way academically, giving him the best possible opportunity to go to the best school in the state in Oklahoma, and encouraging him to not settle for just being an average student there,” Sanford said.

The Cardinal lost the Fiesta Bowl 41-38 in overtime, but managed to outrush the Cowboys 243-13. Five days later, Sanders committed to Stanford.

When he was asked recently whether the Cardinal’s huge advantage on the ground that night had any effect on the recruiting process, Sanford smiled and said, “We had a big leg up before that game.”

“The first time I came out here,” Sanders told the San Francisco Chronicle recently, “I knew this was the place I wanted to be.”

***

Stanford’s campus and team atmosphere are also cited by Seale and Reynolds, who both say that their fathers left the college decision mostly up to them. But even if the Farm is a perfect fit for some of these recruits, what makes so many NFL sons the all-around student-athletes Sanford and his staff were looking for?

From the start of training camp, Shaw raved about Kodi Whitfield’s ball-catching skills and bragged that he had picked up the Cardinal’s sophisticated offense faster than any receiver he had ever seen, an achievement that earned Kodi playing time in each of Stanford’s first two games.

“My old boss Jon Gruden used to talk about hiring coaches’ sons, hiring guys who have lived in the profession before,” Shaw said during fall camp. “They don’t go through the highs and lows. You can trust them when times are hard because they’ve been through it.

“There’s something to be said for players’ kids, in particular, players who went to school here,” he added. “Kodi’s been on this campus a bunch. Kodi understands the culture here, it’s been a goal of Kodi’s to get here … now his dream’s been realized. So he’s one of those guys that walked onto this campus and didn’t blink.”

Even those recruits who were too young to remember their dads’ playing days have access to a first-hand perspective on the grueling, unpredictable life of an NFL player. Nobody could understand better the importance of education when a career came to an end, whether that resulted from injury or age.

“Back when our dads were playing it was really all about football,” Kodi said. “But now our dads are telling us, you know, to get an education and think about life after football.”

Their fathers’ experience also pays dividends on the playing field. Of Stanford’s 10 NFL sons, six — most notably Sanders — play the same positions that their fathers thrived at professionally.

Sanders admits that his dad may have been a more explosive back, though comparisons have still been quick to form.

“He’s just like his dad, what do you know,” was Bob Whitfield’s description of YouTube highlights.

“There’s a lot he’s got to learn about other facets of playing football,” Shaw once noted. “He doesn’t have to learn how to run the ball.”

***

But if certain Cardinal standouts demonstrate anything, it’s that growing up with a football father can go quite a long way, regardless of specific skill sets.

Reynolds, whose dad of the same name played 10 NFL seasons, has quickly impressed as a Cardinal safety in 2012, intercepting three passes in his first two collegiate starts and returning one of them for a 71-yard touchdown against Duke.

“I know [that me playing] was his dream,” said Reynolds, a redshirt sophomore. “Just having him to help my football IQ helped me tremendously.”

The Cardinal coaching staff has noticed that players like Reynolds, surrounded by football from an early age, arrive with a different kind of work ethic.

“They grew up watching the game — not just on TV, but in person — and seeing training camp,” Sanford said. “They understand how it’s supposed to be done at the highest level.”

That mental perspective is often the most valuable thing a former football player can pass on to his son, especially when physical tools are less relevant. Seale, whose father Sam played for 10 years as an NFL defensive back, has watched film of his dad before — but not in search of pointers.

“We make fun of each other,” Seale said. “We always talk about who is better, if I would have played against him, if I would beat him or he would beat me.”

Ricky hasn’t seen much of the field in his two seasons, but he often reflects on his dad’s advice to “always be ready.” You could never know when an injury would bump you up the depth chart — the Cardinal’s is especially lengthy at tailback — or whether any given play would be a big one.

“He was just going to be there for advice,” said Seale, whose dad would only coach him for one season. “He just always told me that if I wanted it, he couldn’t be the one to make me do it; I have to want it myself.”

That hands-off approach, even from a former NFL player, makes things much easier for coaches.

“They do such a great job of encouraging their kids, coaching them, but also realizing that this is their opportunity and we’re their coaches and we’re going to bring them along,” Sanford said. “And the parents tell them to listen to their coaches.”

***

Besides Sanders and Whitfield, Stanford recruiters would nab five others of NFL parentage last offseason: offensive linemen Andrus Peat, Josh Garnett and Nick Davidson, corner and kick returner Alex Carter and linebacker Noor Davis.

Of the seven, Sanders is perhaps the least likely to play this season because of the Cardinal’s depth in the backfield; regardless, his name has attracted so much hype that the coaching staff was forced to cut off the media’s access to the young tailback by the end of training camp. Shaw joked that Sanders was the only player being asked about more than Josh Nunes and Brett Nottingham, who were locked in a fierce competition to succeed Luck at quarterback.

Though Sanders may not play on Saturdays in 2012, many Stanford fans already have him tabbed as the next great Cardinal star. They expect him to carry the torch that Jim Harbaugh lit, Toby Gerhart brought to the postseason and Andrew Luck elevated to two straight BCS bowls.

“[Those men] just cemented the type of quality football that you did not see at Stanford,” Bob Whitfield said. “You know that your son is going to a prominent football school, and then to have the academics to boot just makes it a much more special place.”

It’s the academics, after all, that attract most young prospects’ parents. And if former NFL players are any different in that regard, it’s because they understand the value of a strong education even better.

“After you’re in it there’s still real living, and it doesn’t change things just because people know your name,” Whitfield said. “The biggest thing is just the general conversation [with your child] of you’ve got a task at hand, you’ve got opportunity in front of you. Take advantage of that opportunity. Study hard, work hard, just do all the things that you need to do right. … That comes from any pro, where it’s fourth down and you’ve got to score on this last play. You know you have to do your assignment to be successful.”

Sanford and his staff have been very successful on the recruiting trail. The seven players of pro football progeny in this year’s incoming class outnumber 10 other Pac-12 teams’ total supply — not just their freshmen.

Those NFL bloodlines are a reflection of one thing: In the football world, the Farm is trending up.

“As we walk into living rooms, the actual prospects themselves are more excited about the football,” Sanford said. “Players have said, ‘Hey, they play great football and it’s a really good school,’ and in the past it was, ‘This is a great school, I’m looking for the academics, but I’ve got to find the best football fit for me.’ We really feel like we have the ability to hopefully corner the market in the elite academic-and-football-player-type kids.”

Sanford thinks that the biggest factor in attracting NFL players’ sons is actually out of the hands of the Cardinal coaching staff. The recruiting process really dates back to their fathers’ playing days.

“They might have come across a Stanford guy at one point in their career in the NFL, and they notice something different about those guys,” he said. “Along the way they all had a chance to play with a Stanford guy, and they said, ‘Hey, I want my kid to go to that place.’”

As it turns out, there’s some truth to that theory. Of the 10 NFL players whose sons now wear cardinal and white, nine of them — that’s each and every one who stayed in the league for more than a season — once shared an NFL locker room with a former Cardinal.

Bob Whitfield understands first-hand how significant that is.

“Whenever Stanford’s mentioned, it’s mentioned with the reverence of a great school,” he said of his one-time teammates. “When they understand you’re a Stanford man, they greet you accordingly. I always said it’s good in the film room, but they knock down Stanford people too on that field.

“You know, football is still going to be football. But I think that what happens is that people understand that you’re more than just a football player when you have Stanford behind you.”

Note: The Daily defines an “NFL player” as someone who has actually played in an NFL game, not just been drafted or listed on a team’s active roster. For example, the 10 Stanford sons of NFL players mentioned are redshirt sophomores Ed Reynolds and Ricky Seale, redshirt freshman Kevin Reihner and freshmen Nick Davidson, Noor Davis, Andrus Peat, Barry Sanders, Kodi Whitfield, Alex Carter and Josh Garnett. An 11th player, redshirt freshman Brian Moran, has a father (former Stanford player Matt Moran ’84) who was drafted and listed on the Kansas City Chiefs’ 1986 active roster, but he never played in an NFL game, so he was not included in our total.