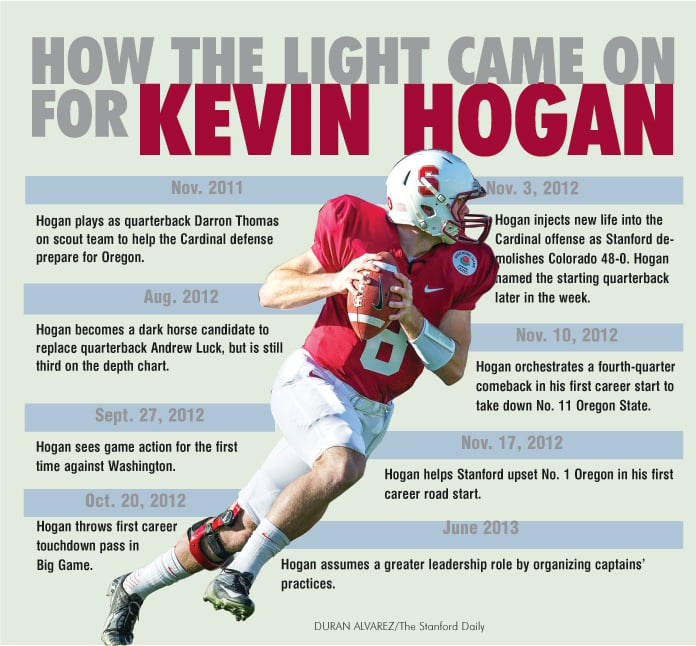

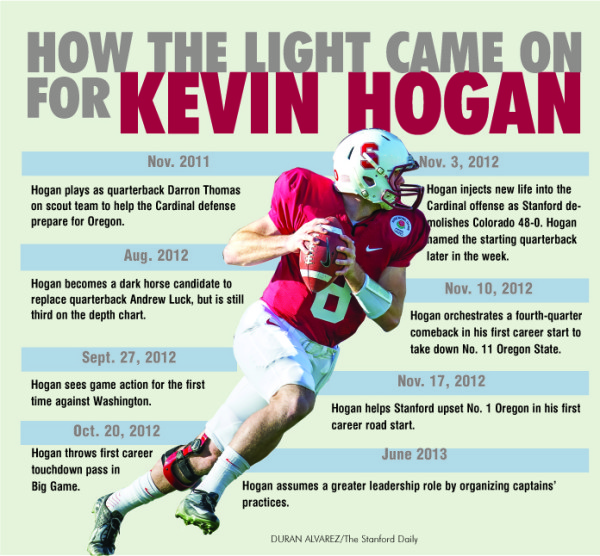

When we first heard it, we thought it was just about Kevin Hogan — a unique phrase, for unique circumstances. How often does a redshirt freshman unseat a senior quarterback on a top-15 team, nine games into the season, much less? One week he was a third-stringer, still an afterthought following the preseason competition to replace Andrew Luck; the next week he was tasked with leading Stanford to the Rose Bowl berth Luck never attained. From the outside looking in, at least, there was something uncanny about Hogan’s ascension.

Only head coach David Shaw’s description could suffice: “The light came on.”

The metaphor was as eloquent as it was simple. For the young, mobile and unpolished quarterback that Hogan was in early 2012, all it took to become the leader of one of the most complex offenses in the nation was that final bit of understanding — an Aha! moment.

But even as Hogan solidified himself as the Cardinal’s starter for 2013, the catchy analogy lived on. This summer, Shaw revisited the phrase in reference to two young defenders, junior Ra’Chard Pippens and sophomore Noor Davis, who were on the verge of achieving their potential; later, junior safety Jordan Richards used it to describe his own development as a player the season before. It became clear that Hogan’s moment of epiphany was not the only one of its kind.

So what is this metaphorical light, exactly? Is it a question of building the physical tools needed to play big-time college football? Is it related to mastering Stanford’s infamously complex playbook? Or is it just about a young player’s comfort level on a new team?

“It’s everything,” Shaw recently explained.

By that, he doesn’t just mean it’s all encompassing. In many cases, it can also be a prerequisite to seeing the field.

“It’s up to us coaches to always look for that in young players,” Shaw said. “Some guys, they’re right there, they’re right there, and then all of a sudden they get it — now it’s up to us to recognize that and use them in places where they are comfortable and they can execute their jobs.”

The light means different things to different people. It remains off longer for some players than for others, and chances are that’s why you haven’t yet seen certain prized recruits play much on Saturdays. Every position has its own intangibles to master, and every player has his own obstacles to surmount.

But one thing is certain. When the light does come on, it’s hard not to notice.

***

If there’s a narrative crucial to the Cardinal in all this, it’s the intellectual aspect of football. Stanford’s coaches know that the elite athletes they recruit are elite students as well, and in turn, they put their players’ cognitive abilities to the test with complex schemes that resemble those used in the NFL.

“I think they put more on our plate because they know we have the ability to understand it,” said backup inside linebacker Blake Martinez, a sophomore. “Today our coach was putting checks in, and we all answered, and he was like, ‘Wow, this makes it easy when we have a Stanford student and player in our pockets.’”

Certainly, the mental barrier once stood in the way of Hogan, who only became the starter once he had learned enough of the playbook and consistently made the right decisions on the fly. That’s to be expected for a position as complex as quarterback. But Stanford players’ smarts aren’t enough on their own.

“The fact that we know our guys are bright enough to take up a lot of scheme, to pick up a lot of different things that we can do, I think that takes away some of the just pure learning part of it,” Shaw said. “But the physical part of it, the emotional part of it, sometimes that’s just growing.”

A big part of that growth is getting used to the speed of college football. With the proliferation of hurry-up offenses such as Oregon’s, Stanford’s defenders, for example, don’t have time to confirm a play call from the sideline with a teammate. And once the ball is snapped, the players across the line of scrimmage move much quicker than the high school opponents that a recruit is used to. The same applies on the offensive side of the ball, especially, of course, for Hogan.

Asked to describe what it looks like when the light comes on for an athlete, both offensive coordinator Mike Bloomgren and defensive coordinator Derek Mason noted that it’s as if “the game slows down” for that player.

“It’s the fact of knowing it and doing it fast,” Shaw said. “It’s one thing to know it. We’ve got a lot of players here, especially young guys — in the classroom they can draw it all up. If you ask them a question, they answer the question. But [it’s another story] when the 40-second clock is going and the defense is changing and they have to change their call from one to the next.”

“When you step between the white lines and you step on the football field, it’s your job to know your playbook,” agreed Mason. “And so that’s where the pressure lies. So I think when you look at the intellectual part, it plays into it, but I think it really has more to do with whether a young man is invested in the process. And the earlier he invests, the more he gets out of it.”

That work is needed to build what Shaw calls a “physical history,” the accumulation of months — if not years — of coaching and reps. And it goes beyond just the complexities of the Cardinal’s playbook. Senior nose tackle David Parry said that for the defensive line, something as simple as yelling “pass” or “ball” each play in practice makes the habit instinctual on game days.

So even in the case of the elusive light, it appears that the old adage holds true: Practice makes perfect.

“My dad calls it, ‘Suns up and suns down,’” Shaw said. “It’s just young players, they need days. They need more days. They need to hear it over and over and over again. They need to see it again and again, and they need to do it again and again… Until it crystallizes, you can’t ever play fast.”

***

The time component alone fails to tell the full story. Some current Stanford players, such as fifth-year senior linebacker Shayne Skov, stepped into starting roles when they were true freshmen and excelled right away. In that regard, Shaw also cited former Cardinal running back Stepfan Taylor ’13, the school’s rushing leader, who backed up Heisman Trophy finalist Toby Gerhart ’10 as a true freshman.

On the other end of the spectrum are players like former right tackle Derek Hall ’10. Hall appeared in just two games his first four years, switching from defense to offense; he was so low on the depth chart, Shaw admitted, that the coaches figured he would never see significant playing time. But the light came on for Hall in the training camp before his fifth and final season, and he started for Stanford at right tackle that year.

“Young men develop differently,” Mason said. “Some young men come in and are ready to play. Some young men come in and it takes longer.”

There’s one moment in a player’s career in which the light is perhaps the most likely to come on, however, and that’s the training camp before sophomore year.

That was certainly the case for senior inside linebacker A.J. Tarpley, who helped fill in for an injured Skov in 2011. Familiarity with the program aided Tarpley in his second go around, but he was also fueled by something else that preseason: having spent a redshirt year on the sidelines, unable to contribute.

“For me, it was just [to] keep grinding, keep working hard,” Tarpley said. “Put your head down, you’ve got nothing to say. Just let your actions do the talking.”

Though many members of Stanford’s 2012 recruiting class, often called the best in school history, also had a chip on their shoulder this offseason, several others are merely looking to take the next step after playing minor roles as true freshmen. Martinez falls into that category, as does offensive lineman Josh Garnett, who is slotted as the backup left guard. Bloomgren said that he wasn’t convinced Garnett would be ready at the end of last season, but that he made enough strides in the spring and summer to become one of the team’s two “Ogre” tight ends.

“[Garnett is] not at a point where he’d feel completely comfortable to play a whole game,” Bloomgren said, “but in all of his roles, he is doing really well.”

“I think the light is starting to come on,” Garnett agreed. “It’s still getting brighter.”

Even though the Ogre role is a bit different than playing guard, where Garnett could very well start in 2014, it gets him onto the playing field consistently on Saturdays. For a young player, that’s a big step toward the light coming on.

“You can see the signs of it in practice, but you can’t fully establish it until game time,” Tarpley hinted. “It probably doesn’t happen until the actual lights come on.”

It didn’t for Hogan last season. He made his first collegiate appearance in a loss against Washington, coming in for one play and making the wrong read.

Hogan got six snaps against Cal three weeks later, firing a laser as he rolled to his right for his first career touchdown pass. That, Shaw has said, is when the light came on. After seeing more time against Washington State the following week, Hogan played most of the game in relief duty at Colorado and took over as the team’s starter one week later. Stanford hasn’t lost since.

“Sometimes it’s overnight,” Shaw said. “Like Kevin. One week, he didn’t get it. He just didn’t get it. And the next week, he gets it. And understands it. And he wants to execute it.”

***

At other positions, the light can be much harder to spot. One of the telltale signs for Shaw is when a player drops his shoulders, as if to say, “I got it.” Even when he was coaching from the press box, Shaw learned to study his receivers’ smallest movements.

“When you coach for a while, you come to look for it,” Shaw said. “I can see a guy’s body language. He leaves the huddle, he’s not real sure — you can see it out here in practice, guys are still thinking as they leave the huddle… But those guys that break the huddle and line up quickly, they know what they’re doing.”

While Shaw is able to gather details from pre-snap alignment, the coaching staff is also concerned with how well its players handle assignment — deciding who to block (on offense) or cover (on defense) — and adjustment — changing those duties before and during the play.

“We talk all the time about Triple-A, which is alignment, assignment and adjustment,” Bloomgren said. “To me, the light comes on when you see them able to anticipate and make those adjustments on the run.”

Nowhere is that adjustment more apparent than under center. Stanford’s quarterback comes to the line of scrimmage with two or three plays and, after evaluating the defense, is tasked with checking into the correct one. That ability is what made Andrew Luck ’12 unique amongst his fellow quarterback prospects, and it’s one of the main skills that Hogan needed to work on last season before he could earn the starting job.

Once Hogan was ready to play, Bloomgren explained, he only got better with the confidence he gained from his dominant performance against Colorado. Though Hogan threw for a modest 184 yards in that game, he got his team into the right play consistently, leading the Cardinal on six consecutive scoring drives.

Confidence is a factor on the other side of the ball as well — though sometimes, Cardinal defenders’ most intimidating foes are the ones they face in practice.

“You need a physical light to come on,” Martinez said, “because when you’re coming up and you have to go up against [senior guard David] Yankey and that type of big, muscle, physical, huge man-beast, you just have to think, ‘Oh, I have to get this. I can’t be scared. I’ve got to go. I’ve got to be able to strike, get off and use all my techniques.’”

And if a player can focus on his technique, that means he’s not thinking as much about the play itself. The game becomes more automatic; finally, it slows down.

“You realize it in the games, or even in practice, when you don’t have to think as much,” Garnett said. “Like, ‘Oh, yeah, I would’ve never known that last year.’… That light really clicks, and you know what you’re doing without having to really think about it.”

“[It’s] the ability to go up there and not be thinking about the snap count, not be thinking about, ‘Who do I block?’” Bloomgren added. “It’s the ability to get up there, get in your stance and fire off and hit somebody in the face and drive them forever.”

***

Hogan won all five of his games as a starter last season, the first four against ranked teams and the fifth against Wisconsin in the Rose Bowl. But even though Hogan’s light had come on — he had grasped the playbook, he had learned the checks and he had the confidence to do it all in a big game — his development was not complete. This offseason he led players-only captains’ practices during the summer, scripting plays for the offense as a coach would during the season.

It’s a step that the coaching staff loves to see.

“He starts to take a vested interest in what we do and actually what his work looks like,” Mason said of a developing player. “He actually starts to autograph his work… I see the light coming on when a young man really starts to take to heart what his work looks like.”

Shaw’s expression, then, needs some clarification. The light may come on in an instant, but it needs some time to get brighter — just like the stadium lights referenced by Tarpley. And even though that special moment of clarity is easier to notice, easier to report about and easier to pack into a deceptively simple phrase than the continued development that follows, at the end of the day, it’s not really everything.

Details aside, the light metaphor will again be a part of Stanford’s narrative in 2013. Stanford’s roster is littered with players whose shoulders have dropped in the last 12 months — Hogan, Parry, Garnett and Martinez, to name a few — and its ranks are filled by dozens more who are waiting for their own time to come. While the Cardinal probably won’t have another upheaval at the quarterback position, chances are that a few new faces will make it onto the field on Saturdays this fall.

No one can say whose light will come on next, of course, and it’s much harder than just flicking a switch. But that won’t stop Stanford’s coaches from looking for that spark.

“If you could bottle it and sell [it],” Bloomgren said, “we’d all buy it.”

Contact Joseph Beyda at jbeyda ‘at’ stanford.edu.