Annie Robinson turns 10 next month, but her dad will be on a business trip that night. The Southern Utah men’s basketball team will be in Missoula, Mont., and Pops has a game to coach.

If you follow Stanford basketball, you probably don’t know much about the Thunderbirds. Yet you have heard of Annie, maybe by a different name, the one that broadcasters Brent Musburger and Dick Vitale proposed on national television 10 years ago today.

“Buzzer-beater.”

Some call it “The Miracle at Maples”; others, simply “The Shot.” But when Nick Robinson ’04 M.A. ’05 sunk a 35-foot runner as time expired to give No. 2 Stanford an 80-77 win against No. 12 Arizona — sending Musburger and Vitale into hysterics, the Sixth Man Club onto the Maples Pavilion hardwood and the Cardinal to a 20-0 record — there were, in truth, no words to describe what had just happened.

Ten years after Robinson’s iconic shot, that has changed.

“As a huge Stanford fan in pretty much any sport, this was one of the greatest games I’ve ever been to,” Tiger Woods told The Daily through his agent last month. “To come back like that, and with that type of shot, is something I’ll never forget.”

“It’s one of the best finishes I’ve ever seen,” added Heisman Trophy winner and Super Bowl MVP Jim Plunkett, who sat behind Woods at the game. “It goes down with the great Stanford historic moments.”

The moment itself has lingered in the memories of Cardinal fans for a decade, and it has stuck with members of the 2003-04 hoops team as well. Rob Little ’05, then Stanford’s starting center, has a framed photo in his house of Robinson shooting the ball; Josh Childress ’05, the team’s star forward and a seven-year NBA veteran, still gets chills watching that clip.

But the story of Feb. 7, 2004, is not just one of an improbable steal and an impossible shot. It’s one of a fierce West Coast rivalry, hitting its unforgettable zenith; of a basketball-frenzied campus, converging on its beloved stomping grounds for one final season; of a 24-year-old utility player, at once the odd man out and his team’s most respected member; and of a group of 14 conference champion teammates, the likes of which haven’t been seen on the Farm since.

They were a team in the fullest sense of the word, the phoenix that rose out of the ashes of four NBA departures — Jason and Jarron Collins, Casey Jacobsen and Curtis Borchardt — in two years. That old guard had set a new standard for Cardinal men’s basketball under head coach Mike Montgomery, starting the 2000-01 season 20-0, holding the No. 1 spot for much of that year and reaching the Elite Eight.

Facing a significant experience gap entering the 2002-03 season, Stanford was picked to finish seventh in the Pac-10. But instead of going their separate ways for the summer, as most college players did at the time, the entire Cardinal roster stayed on campus to train. They had seen an earlier generation of teammates make Stanford an elite college basketball program, and they wanted to do the same. The team finished second, and the next summer, it followed the same routine to prepare for the 2003-04 season.

“We felt that we had the talent to [return to the top],” says the team’s junior point guard, Chris Hernandez ’05 M.A. ’06. “We held each other accountable, people calling people up if they didn’t show up for a voluntary workout and whatnot.”

“Everyone was the one guy trying to play the hardest in practice every day,” adds Joe Kirchofer ’03, one of the team’s three captains. “It wasn’t just one of us; it was everybody trying to set that tone, which made it really fun.”

Most important was a lack of ego from Stanford’s top players, including from the most talented of them all, Childress.

“Our best players wanted the team to be successful more than they wanted themselves to be successful,” Kirchofer says. “I think Josh Childress deserves a ton of credit for the way that we all approached the team and the way that we were able to work together so effectively.”

Though Childress was just months away from being selected sixth overall in the NBA draft — higher than any other player in Stanford history — the talented forward brought a calm focus to Cardinal practices.

The vocal leadership was left to Kirchofer and guard Matt Lottich ’04, a deadly 3-point shooter and the team’s second-leading scorer. He was the team’s most competitive player, and unlike Childress, he let it show.

“The guy was in your face, talking smack in practice, kind of getting people rough,” Hernandez remembers. “Sometimes you’re going through practices and you’re working hard, but your mind might not be really there. You’re thinking about the 20-page paper you have to write later that night or all the different stuff that goes on at school. And sometimes you get someone who can sense that. They get in your face, they get you focused, get you mad so that you want to really compete and beat that person.

“But you can’t have five people who are like that,” he adds, “because you would never get anything done. Everyone would just be yelling at each other all the time.”

The Childress-Lottich foil exemplified the team’s diverse personalities. There was the philosophical Little, a 6-foot-10 center whose opinions were as thoughtful as his name was ironic; Justin Davis, a comedic big man who could lighten the mood in an instant; and Kirchofer, a fifth-year leader whose positive attitude and work ethic had made him a primary backup over a long career. Setting the tone on the court was Hernandez, who returned after breaking his foot twice and missing the entire 2002-03 season, instantly making the Cardinal better with his mistake-free play and ability to read the game.

Nick Robinson wasn’t an injury-hardened vet, a future NBA talent or even a trash-talker, but in this cast of characters, it was he who stood out. Robinson had originally signed with Stanford in 1997, but he took two years off for a Mormon mission in Brazil, where he kept in practice by playing against his fellow missionaries on an outdoor court. When Robinson finally made it to the Farm, he was as old as the team’s juniors.

“I had never met Nick, but I was really excited because we were two freshmen coming into the team,” Lottich remembers. “And all of a sudden, he’s on campus saying things like, ‘Yeah, I got married last week.’ Our lives were very different, very quickly.”

Instead of living in the dorms, Robinson and his wife Meagan moved into the on-campus couples housing in Escondido Village. By the start of the 2003-04 season, Nick was the oldest player on the team even though he was just a junior athletically.

“He could’ve been living on the moon, his lifestyle was so different than ours,” Kirchofer says. “But his wife was pregnant and we were super-excited, like the whole team was getting a little brother or something.

“A little sister, as it were.”

Annie was due on March 1, 2004. Robinson’s teammates started calling him ‘Pops.’

Despite his family responsibilities, Robinson was no outcast. His perspective may have been different, but Lottich remembers that it kept the team even-keeled, and Childress says that Robinson’s opinions were always valued highly. The team even saw Meagan’s home-cooked meals as a chance to get away from the college lifestyle.

“I’ve played a lot of basketball since then and I’ve coached basketball, and I haven’t really been a part of a locker room that was that tight,” Lottich says. “I haven’t been part of a group of guys that I trust more, both on and off the court, than that group…There’s no doubt in my mind that if one of them calls me right now and needs something, I’d be on the next plane out. It was that special.”

On the court, Robinson was the final, invaluable piece in the Cardinal puzzle. He was usually listed as a forward, but he played all over the floor, guarding different positions, creating steals and contributing a few buckets a game — in Robinson’s own words, doing whatever he could to help.

And the Cardinal needed all the help it could get early in the season, with Childress out for over a month with a stress reaction in his foot. But Stanford rolled through nonconference play, knocking off then-No. 1 Kansas in a win that shocked everyone but the Cardinal. The team amassed a 9-0 record and rose to No. 5 in the country before Childress’ return for the Pac-10 opener.

“We felt like that with him and with everybody at full strength, we would be poised for a really special season,” Robinson says.

Slowly but surely, Childress made his way back onto the court: seven minutes against Washington State, 13 against Washington, 26 at Arizona State. 9-0 became 10-0, and 11-0 became 12-0.

Childress’ first start of the season came in the Cardinal’s sixth conference game, a 67-52 thrashing of UCLA. 15-0. Suddenly, Stanford was one of just two undefeated teams in the country. 16-0. 17-0. Questions about the streak started flowing in.

“On a team like this it’s impossible to have things not occur to you, because all the sportswriters need something to write about,” Kirchofer says. “We knew we had a chance to do something really special, but there was never any thought that we had done something special. It was all a work in progress.”

Second-ranked Stanford rolled into Eugene, Ore., on Jan. 31 without the services of Davis, who had hurt his knee in win number 17, and for the first time all year, the Cardinal wasn’t able to pick up the slack. A middling Oregon team jumped out to a 45-26 lead. Nothing was working; Childress was having an off night, Robinson was 1-of-8 from the field and Little played just five minutes due to foul trouble.

Stanford called timeout.

“Nobody was in there talking about, ‘Oh, what if we’re not undefeated tomorrow,’” Kirchofer remembers. “It was more just about getting it done.”

“I remember our assistant coach, Russell Turner, just got in my face and started ripping me a new one,” Hernandez says. “Obviously I’m paraphrasing, but, ‘When are you going to play? You going to start playing?’”

That’s when the Cardinal’s point guard, its self-proclaimed distributor, flipped the switch. Hernandez became aggressive, driving time and time again, making trip after trip to the free-throw line. All 22 of his points came after halftime, and with the help of 19 points from Davis’ replacement, sophomore Matt Haryasz, the Cardinal escaped 83-80.

Halfway through the conference season, Stanford was still undefeated. The phoenix had taken flight.

Lute Olson steps off the bus at the top of the loading dock behind Maples, and the boos commence. He turns to their source, a group of about two-dozen Stanford students gathered on an overlooking pathway. Olson tries to say something, but he can’t be heard over the crowd. Finally, he gets through. “You should be at ASU,” he tells them. “You’ve got that kind of class.”

It’s Saturday morning, and the Sixth Man Club has been waiting all week for the venerated Arizona coach’s arrival. The first ones arrived at Maples on Tuesday, pitching their tents on the chilly concrete. The early few slept there for four nights through the cold and the rain, not for tickets — they had those — but for front-row seats.

There was a brief respite on Thursday night for Stanford’s 81-51 win against Arizona State. Afterward, the crowd only grew. A couch was hauled over; many of them had done this before. By Friday night, Maples was hosting its own party, complete with booze, dancing and a karaoke machine. Well past midnight it continued, until the students decided to get some shut-eye before Saturday’s noon tip.

The team has developed its own counterpart to the Sixth Man’s tradition. Around 9 a.m., not long before the arrival of the Wildcats’ team bus, a few Cardinal players stopped by to deliver donuts to the students.

“I can honestly say there were games that [the students] did make me play hard,” Childress says 10 years later. “It’s a different level of adrenaline that you get from your home crowd cheering you on.”

“They were at every game, and they packed that sideline,” Robinson remembers.

2003-04 is Lottich’s senior season, and over the last four years, he has grown to believe that the Cardinal has the best home-court advantage in college basketball. But while it helps to have students camping out for several games a year, at least some of the credit has to go to the court itself.

At a school as unique as Stanford, perhaps it’s fitting that the Maples of 2004 has its own quirk: the floor. If you look closely at the court, you can’t see anything special; it’s just any other hardwood floor, just sitting there.

Until you feel it move.

Built on four layers of crisscrossing beams, the one-of-a-kind surface is meant to be springier than any other in college athletics. The thinking was that an extra little bit of give would reduce players’ injuries while also allowing them to jump higher.

And oh, do the students jump.

Their old wooden bleachers, really, are one with the court, and the Sixth Man Club likes to make its presence felt. Literally.

“I can remember coming in as a high school guy, watching a game, Arizona-Stanford,” Hernandez now says. “This Arizona power forward was at the line shooting, and the Sixth Man was just rocking the benches over on the side. It was so loud, and they were jumping so hard, that the floor was moving, and it was making the basket move. And Lute Olson is on the side just screaming at the refs to stop the game and make the students stop so the player could shoot the free throw without the bucket moving.”

The most publicized incident of Olson stopping a game at Maples due to a shaky basket during free throws came in 1988, when the Cardinal upset the No. 1 Wildcats. Hernandez would have been just 4 years old, so chances are, the basket-shaking happened more than once.

“When I was in high school, when I’d come up for unofficial visits, I’d come for the Arizona-Stanford game,” Hernandez adds. “It was just a different type of energy.”

Though the students camping out for today’s game weren’t around for the rivalry’s inception — by most accounts, it was sparked by that 1988 upset — they have watched it intensify with Stanford’s new levels of success in recent years. The rivalry’s vitriol was renewed in 1996, after the Cardinal upset No. 9 Arizona to snap a 15-game losing streak to the Wildcats. Two years later, Arizona secured an outright Pac-10 title by embarrassing the second-place Cardinal 90-58 at the McKale Center, but the next season at Maples, Stanford clinched its first conference championship in 36 years with an emotional win against those very same Wildcats.

Kirchofer stepped onto the Farm the very next year. In his first nine games against Arizona, he has seen the teams go 5-4, with an average margin of victory of just five points. But though they have won the Pac-10 three of those four years, the conference’s two superpowers are not alike.

“Stanford basketball, for most of Coach Montgomery’s tenure, was a tough, hard-nosed program,” Kirchofer says. “And Arizona, at the time, was — ’the opposite’ is a little bit harsh — but they were a team that was really explosive and fun to watch, but really, really unpredictable and all over the place. And they were good and had lots of good players, and we knew they could be really good. But we also, I think, wanted to show that our approach was superior, and wanted to make a statement that they had some good players, but they really couldn’t hang with us as a team.”

The Cardinal made that statement early in the season, when it handled the No. 3 Wildcats 82-72 on Arizona’s home court. (Stanford led by 20 with four minutes left.) It was the team’s fourth straight win at McKale, and it spurred a telling joke on the trip home.

“We said, ‘Well, we can’t wait to go home and look at the highlights from our game,’ because they’re going to all be Arizona’s,” Lottich says. “They were a flashier team, they were more athletic, they jumped higher, they got in all the SportsCenter highlights. But at the end of the day, we got some Ws.”

The 2003-04 Arizona team is particularly skilled; its starting five of Andre Iguodala, Channing Frye, Mustafa Shakur, Salim Stoudamire and Hassan Adams will all go on to play in the NBA. And as successful as the Cardinal had been at McKale, this generation of Wildcats has been unfazed by the hostile environment at Maples, earning four straight victories on the Farm. If No. 2 Stanford wants to extend its perfect season, it has to take back its home court.

“The part that I remember most about the series is that more often than not, the away team won the game,” Little says. “We were just really amped up to win at home.”

The Sixth Man, too, has been waiting for this game, which is why they’re overlooking the loading dock in the early hours of this fateful Saturday morning.

The first Arizona players step off the bus now, and the boos rain down once again. One of the students shouts something about Stoudamire’s cousin Damon, an Arizona alum and current NBA player who was recently arrested for marijuana possession.

It’s the morning of Feb. 7, 2004. Beats By Dre won’t be founded for four more years, but several Arizona players have their headphones glued on as they walk past the crowd’s persistent shouts.

One by one, the Wildcats descend the ramp and enter Maples Pavilion. The students go back to their tents. For now, it’s quiet.

***

Usually, Plunkett would be the celebrity in those second-row courtside seats. Not today. Vitale and Musburger are sitting at the broadcast desk to his right, while Woods is with his fiancée, Elin Nordegren, just a few seats to the left of Plunkett in the front row. Vitale took photos and signed autographs with the Sixth Man before the game, and a few students brought a sign imploring Nordegren, a Swedish model, to marry them instead of Tiger.

That’s not to mention the man himself.

“Every time I ran down that side of the court, I was sort of mindful that [Woods] was sitting right there watching the game,” Little says. “And this was, like, pre-controversy Tiger. This was when Tiger was untouchable, the best athlete in the world.”

For much of the game, No. 2 Stanford has looked like the best team in the country, stretching its lead to 12 points in the second half. But Arizona has turned the tables with a 14-0 run late in the game, and a Stoudamire 3 has given the Wildcats a 77-73 lead at the one-minute mark.

Childress sinks a free throw with 44 seconds left to make it 77-74. With a stop, Stanford will have a chance to tie the game up with a 3-pointer in the final moments.

Frye wastes no time inbounding the ball, flipping it to Shakur in front of the Cardinal bench, but Hernandez is there, swatting at the pass and knocking it loose into the corner. He dives at the ball, but Shakur is quicker and scoops it up as Hernandez goes flying into the row of folding chairs. Shakur is immediately pressured by Childress. He muscles the Stanford forward to the ground and lobs a pass over Lottich’s outstretched arms to Stoudamire. Lottich stumbles over Childress.

All Stanford needed was a stop, but it has taken just four seconds for the broken play to put three Cardinal players out of position.

Luckily for Stanford, Stoudamire hesitates across midcourt, giving Lottich just enough time to catch up to the play. The Cardinal’s most competitive player makes a mad dash past Stoudamire, forcing him to spin toward where Woods is sitting, and by the time Hernandez has made it to half court as well, Stoudamire is facing his own basket. Startled, he lofts an errant pass to Shakur, but it’s headed over the half-court line. All Shakur can do is catch the ball in midair and launch an off-balance pass back to Stoudamire.

Lottich leaps and knocks it away.

He corrals the loose ball and hurries downcourt. Thirty seconds left, and Stanford’s best 3-point shooter has the ball. Lottich is chased into the right corner by an Arizona defender, and he’s forced to give it up, firing a pass to Hernandez near the top of the key. Hernandez flips it back to the right, where Robinson is standing behind the arc. For a split second, he’s open.

But like many a home-cooked dinner, Robinson hands it over to a teammate.

Hernandez catches the return feed, takes a dribble left and finds Childress, who has made his way in front of the Cardinal bench while his teammates were drawing the Wildcats to the opposite corner. Childress is 6-foot-8, but this is his favorite spot on the court. His shot rattles in.

For a second, the Sixth Man Club hangs in midair, returning to the ground with a collective thump. Tiger gives a rendition of his trademark fist pump. Olson, ever at odds with the elements at Maples, calls timeout. 77-77.

“The crowd went nuts,” Hernandez remembers. “We all kind of knew that it was our game.”

At least for Stanford, no sequence could better symbolize the fundamental dichotomy of that rivalry. The Wildcats’ skilled but unpredictable playmakers had committed a disastrous turnover, while the team-oriented Cardinal had capitalized by swinging the ball around between four players in as many seconds.

As the initial roar subsides, anxious mumbles begin to fill Maples. The clock reads 23.2 seconds, and Arizona has the ball with no intention of giving it up. The best the fans can hope for is overtime.

But on the Cardinal bench, that hopelessness never sets in. Montgomery is too busy calming his team down, going over the defense. Lottich points out that Stanford only has five fouls, meaning it can commit one more to throw off the Wildcats’ timing without risking any free-throw attempts.

And so the huddles break, with the Sixth Man exchanging “Go”s with “Stanford”s from across the court. That gives way to a unified, drawn-out yell, and as the Sixth Man begins to bounce, those old wooden bleachers begin to rumble.

***

Robinson steps out onto the court. He’s played almost the entire game, as Davis is still injured and Haryasz sprained his ankle in practice last week. With those two healthy, maybe he would be taking a seat right now instead.

Iguodala inbounds it to Stoudamire, Arizona’s best shooter, and the clock ticks down.

Stoudamire takes it upcourt slowly. Lottich watches him closely across the midcourt line, blocking his move to the left, and Stoudamire bounces it back to Iguodala, who is being guarded by Robinson.

They want to get it to Stoudamire, Vitale cautions. They want to get it to Stoudamire.

Iguodala tosses it back to Stoudamire in another awkward exchange near midcourt; the crowd lets out half a gasp, expecting a steal that won’t come. Ten seconds left.

“I’m hacking [Stoudamire],” Lottich remembers. “I’m literally trying to get a foul called on me, and they’re not doing it. They were not going to call it. I don’t think the refs knew [we had a foul to give].”

They’ve got to hurry now, seven seconds, Musburger replies. Here he comes, it’s one-on-one with Lottich…

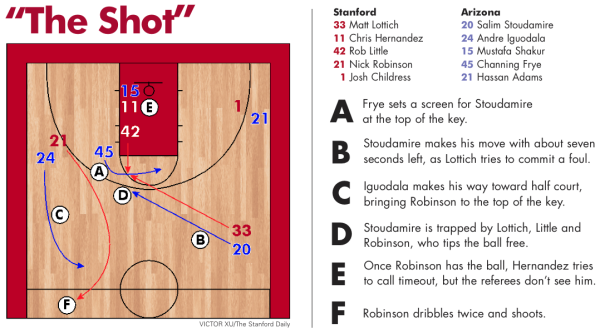

With his right arm on the aggressive Lottich, Stoudamire begins to make his move. From in front of the scorer’s table, he dribbles slowly to the top of the key, where Frye, trailed by Little, is setting a screen. Simultaneously, Iguodala wanders from the left wing toward half court, drawing Robinson to the same exact spot.

…Lottich stays…

Frye releases from the screen a bit too early. Five seconds left. Stoudamire looks up. Lottich, Little and Robinson surround him on three sides.

He tries to pick up his dribble, but Robinson tips the ball free.

…almost stolen…

It caroms off Lottich’s left knee and right into Robinson’s hands. Hernandez frantically signals for a timeout, but the refs don’t call that either.

…they’ve got it! Two seconds! ROBINSON…

Without thinking, Robinson turns upcourt at full speed. He sees the clock, takes two dribbles. They carry him to half court, where he picks up his dribble with just over a second left. By the time the ball is out of his hands, only a few tenths remain.

…AT THE BUZZER…

“I was almost directly behind Nick,” Little says. “All I remember is, ‘Oh my god, that looks like it’s going in.’”

Robinson is looking too. The ball hovers in flight for a brief moment as he lands on his left foot, turned around by the release. Robinson falls to the court, still holding his stare, just as the ball hits nylon.

“It felt good,” Robinson remembers, “and it happened to go in.”

…YES! YES! YES!…

Matt Lottich falls on Robinson first. A split second later, he’s joined by Little and Hernandez. Childress doesn’t jump on top; he has a cramp.

“And then,” Robinson says, “I felt half the Sixth Man fall on top of me.”

…ROBINSON AT THE BUZZER!…

“It got really heavy, really quick,” Lottich says. “And I actually got kind of scared. Like, ‘Guys, get off.’ I started ripping people off of Nick.”

“I feel like I’m going to suffocate in this big pile of people,” Little says.

…STANFORD STAYS UNBEATEN!…

The entire Stanford bench races to the growing dogpile — except for the Cardinal’s fifth-year senior.

“I just wanted to make sure,” Kirchofer says. “I did a double check, was like, ‘Alright, the score’s on the scoreboard, the ref said it’s a 3, it’s in time,’ all that kind of stuff. ‘The game’s over.’”

…IT’S A MOB SCENE!…

“And then everybody was just going crazy, and after I don’t know how long I was thinking this stuff, it was a little bit of, ‘Okay, let’s make sure Nick doesn’t get crushed under this pile. All right, everybody, calm down, calm down. Back up a little bit.’ And then he stands up. ‘Oh, yeah, he’s okay, he’s alive! Let’s party.’”

Not everyone escapes unscathed.

“They ran around me,” Plunkett says, “because I was obviously bigger and stronger, but my wife got knocked down and her leg got caught in one of the folding chairs, and they were using that as a trampoline to get onto the court. So my wife was hurt pretty severely.”

…AN INCREDIBLE ENDING!…

In seconds, the Sixth Man bleachers are empty. The floor starts bouncing like it never has before. “All Right Now” is playing somewhere, but it can’t be heard over the crowd.

“Picture, like, the most populated frat party you ever went to,” Hernandez says. “You just can’t move. That’s what it felt like.”

“I enjoyed the pandemonium,” Childress remembers. “I don’t know about anybody else.”

…CHILDRESS TIES IT WITH A 3…AND…ROBINSON ON THE STEAL…IT’S A RUNNER AT THE BUZZER!

The team snakes its way through the crowd and is whisked into the shelter of the hallway. Lottich peeks back out, and he sees his best friend hanging on the rim, riding a wave of black Sixth Man Club t-shirts. The team makes its way into the locker room, bear-hugging Robinson all the way.

24 years old, Vitale says over the highlight. His wife might have the baby tonight! She’s scheduled to have a baby March 1! She’ll probably jump with joy!

That child will be named “Buzzer-beater,” Musburger jokes.

Buzzer-beater!

Back in the locker room a few minutes later, Montgomery starts giving his postgame speech to the team. Tiger Woods pokes his head in. Nordegren is with him; she checks to make sure the players are all dressed before coming inside.

Woods addresses the team briefly, thanking the players for pulling out the win. But that’s not what they will remember most.

“Tiger, great to see ya,” the quick-witted Montgomery says. “But what the guys really want to know is, does your fiancée have a younger sister?’”

A big cheer goes up.

“Actually,” Nordegren replies, “I have an identical twin.”

The locker room erupts. This time, they’re not constrained by the weight of the Sixth Man. There’s screaming, laughing, dancing. Someone asks for her number. Montgomery, sensing that things might be getting out of hand, finally cautions his players to calm down.

Woods goes around the room, shaking each player’s hand. Finally, he comes to Lottich, who is sitting by the door. Lottich thanks Tiger for coming.

“Great game, Matt,” Woods replies.

“And I remember being like, ‘Wow, Tiger Woods knows my name!’” Lottich says.

Outside, Maples is still bouncing.

***

If you look closely at the court, you can’t see anything special; it’s just any other hardwood floor, just sitting there.

And that’s all it is. You can’t feel this one move.

A lot has changed in 10 years. Tiger Woods is no longer untouchable, Elin Nordegren is no longer at Stanford basketball games and the Maples Pavilion floor is no longer springy.

Not long after Nick Robinson’s shot, that hallowed hardwood was sawed off as part of a $26-million renovation in 2004 that added a concourse, a four-sided scoreboard, new locker rooms and retractable lower bowl seats in the place of the old wooden bleachers. The thinking was that the extra little bit of give in the surface actually contributed to foot injuries, such as those suffered by Chris Hernandez in 2002 and Josh Childress in 2003.

The floor was sold off to fans that summer. A 9-inch by 9-inch block went for $97, plus a $6 surcharge. The email receipt, delivered through the Stanford Athletic Department’s ticketing system, gave the item a simple, fitting listing: “MAPLES.”

“Actual Piece of Historic Stanford University Maples Pavilion Floor, 1969-2004,” the labels on the blocks read. And those fans were, indeed, purchasing their own little piece of history. The final men’s basketball game to be played on that floor was a 76-55 win against Oregon that extended No. 1 Stanford’s school-record winning streak to 25 games.

For the Cardinal, it was part of a whirlwind month to end the season. The team had hosted a baby shower for Meagan not too long before that Oregon win, which served as an emotional Senior Night for Josh Childress, Justin Davis, Joe Kirchofer and Matt Lottich. Two days after the victory, Annie Lee Robinson was born. March 1, right on time.

On the next weekend’s road trip, Stanford trailed a sub-.500 Washington State team by five points with under 30 seconds left, and in quick succession, a four-point play, a Cougars five-second violation on the inbounds and a fadeaway prayer by Lottich — at the buzzer, of course — kept the perfect season going.

But 26-0 is where Stanford’s magic would end. On the verge of becoming the first Pac-10 team to ever finish its season perfect in conference play, the Cardinal lost its 18th and final conference game at Washington.

“I think we honestly let the pressure get to us,” Hernandez says. “Every single day, people would be asking us about the streak, and becoming the first team in Pac-10 history to go undefeated in the regular season. I think as a team, we just choked and let the pressure get to us. And it was devastating.”

Stanford got some measure of revenge when it handled the Huskies in the Pac-10 Tournament Final. But the Cardinal wasn’t playing its best basketball anymore, and it was knocked out of the NCAA Tournament in the second round by eighth-seed Alabama.

A special season was left shrouded in what-could-have-beens. No Final Four. No perfect record. The conference title is remarkable in hindsight — Stanford hasn’t won one since — but at the time, it was the fourth in six years for the Cardinal.

And so we were left with a moment — a shot. To varying degrees, it has stuck with members of the 2003-04 hoops team as well. Little says that when he sees a buzzer-beater every month or two, he instinctually compares it with Robinson’s. Hernandez is taken back to the euphoria he felt in that postgame celebration whenever he sees the joy on the face of a player who has just made a miraculous shot.

Yet for the man they called Pops, the strongest memories are not the ones of the Arizona game.

“I generally think about [the shot] when people ask me about it,” Robinson says. “I think more about that team, and how special that team was, how connected we were.”

That game may be just a symbol of something greater. But 10 years after it all came together on one floor — a heated rivalry, waged in the final seconds for half a decade; a jumping student section, forged in a common bond of camping on cold concrete; a team of champions, as diverse in personality as it was unified in spirit — it’s hard not to acknowledge the power of Feb. 7, 2004, the day when one impossible shot made that floor bounce higher than ever.

The new Maples Pavilion turns 10 this year. It hasn’t seen a moment quite like that one. Chances are, it never will.

Contact Joseph Beyda at jbeyda ‘at’ stanford.edu.