One long week in May, exactly 20 years ago, a hunger strike sent shockwaves through a campus now known less for its sense of activism and more for its ability to churn out Silicon Valley startups.

“We wanted everyone to see us,” said Eva Silva ‘94 M.A. ‘95, reflecting on the events that marked one of the largest and most coordinated protests in recent Stanford history.

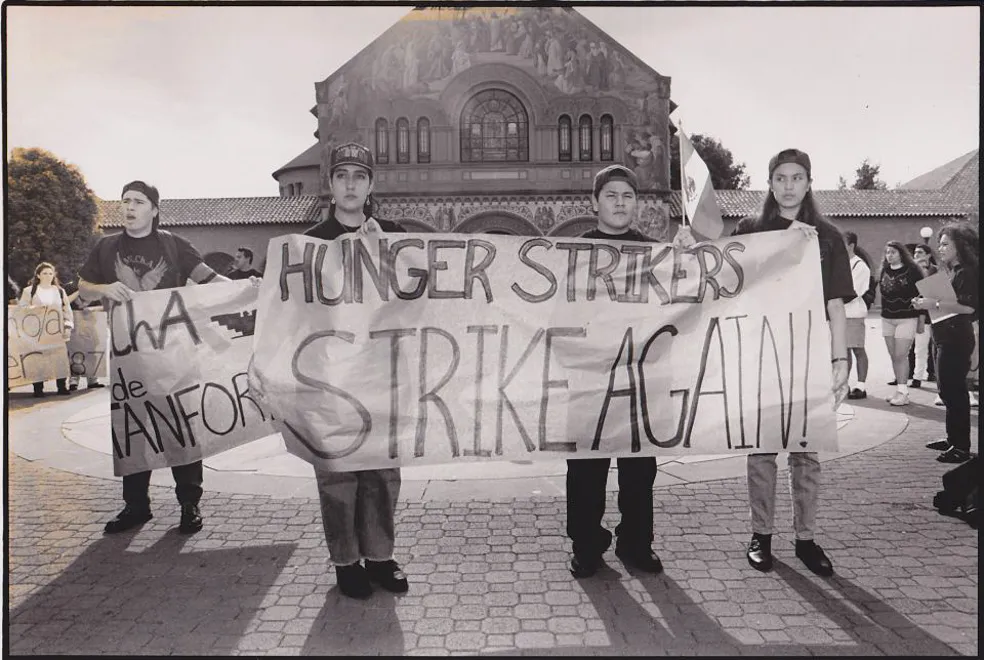

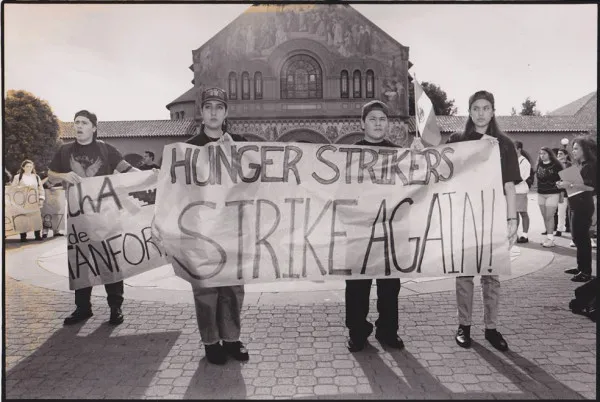

‘We’ was a group of four Chicana students, backed by MEChA de Stanford — the Chicano/a group on campus — and various faculty members, who went without food for three days as they camped out in the Quad in tents.

The protests, Silva said in an interview immediately following their conclusion, “were a buildup of a lot of things that had been happening across campus and in this country about the status of Chicanos and Chicanas.”

And the complaints were numerous. But four injustices, in the eyes of the protestors, loomed largest and hurt the most.

The spark

Condoleezza Rice was the University’s Provost in 1994, second in command to President Gerhard Casper. Her role included overseeing the budget at a time when the University was running an annual deficit in the range of $18-20 million.

As part of her plan to reduce and ultimately eliminate the University’s deficit, Rice eliminated redundancies within the University’s administration. No department or position was safe from cuts.

On the chopping block was Cecilia Burciaga. Her position as associate dean of student affairs was deemed redundant and folded into the Office of Development. At the time, Burciaga, who had been at Stanford for 20 years, was the highest-ranking Latino/a administrator at the University. In addition, she and her husband Tony Burciagawere the resident fellows at Casa Zapata.

“She’s an important contact for us,” said Tamara Alvarado ‘95, one of the four hunger strikers, in a video interview recorded immediately after the strike. “There are so few of us here, and so few of Chicano/a role models…she always has time to hear us out.”

Burciaga’s role as a mentor for many of the Latino/a students on campus made the fact that she was laid off even more difficult for a community that was already struggling with its identity at Stanford. Many of the students that would ultimately become the organizers of the protests felt her layoff was another example of University administrators’ failure to understand and respect the different ethnic communities on campus.

Stanford’s culture today can only be described as different from what it was in 1994. There were concerns about diversity from both sides of the issue — some argued there was too little; others argued there was too much.

Much about the era can be gleaned from the May 1, 1994 FLiCKs showing of “Mrs. Doubtfire.” Before this feature presentation, the leaders of FLiCKs, in a move that was quite common at the time, allowed MEChA to screen “No Grapes,”a short film about the labor conditions of California grape pickers.

Grapes would eventually become an issue of greater significance in the protests, but on that night they served merely as a catalyst for some racist remarks.

“Beaners go home” and similar tauntsechoed throughout the auditorium.

“Students were also throwing food,” Silva recalled. “We needed to educate students about our cause and our community.”

The Chicano/a community had had enough, and decided that a hunger strike was the best and most effective course of action.

“I think it was the only way it would touch their hearts and [make them] stop and think about [the issues facing the Chicano/a community],” said Elvira Prieto ‘96, one of the hunger strikers and now the associate director at El Centro Chicano, after the strike.

“We looked at different kinds of actions,” Alvarado said. “We were also heavily influenced by Cesar Chavez — he did many hunger strikes for many issues.”

The strike

The four hunger strikers came well prepared to the Quad on Wednesday, May 4, armed with tents, water, blankets and mattresses for a strike that, in theory, could continue indefinitely. They came with a resolve to continue the strike until they were satisfied. They also came with demands — a list of four — and an envoy of supporters. The demands covered a wide range of issues that the strikers thought would strengthen the Chicano/a community.

The first and perhaps most unrealistic demand was for the administration to find another position for Burciaga.

“We asked for an apology for Cecilia,” Silva said. “We wanted her back, but we knew in reality it would be difficult [for us to secure her another job within the university].”

The second demand was the creation of a Chicano/a studies major.

“The Chicano Studies major was envisioned back in the 70s, and we’ve been waiting since then. Chicanos are coming to be a majority in California, maybe in the whole country after a while,” said Julia Gonzalez-Luna ‘94 M.A. ‘95, another one of the hunger strikers, in the video after the conclusion of the strike. “It’s about time these issues get recognized and people realize we are not going to go away.”

The third request was perhaps the most contentious and least understood: a campus-wide ban on grapes. The demand was an attempt to better the working conditions of the grape pickers, who were exposed to pesticides while working in the field and, the protesters believed, were disrespected overall.

The final demand was the construction of a Stanford Chicano/a community center in East Palo Alto, as a means of connecting Stanford to the greater community.

The first day, the team of negotiators — comprised primarily of Jorge Solis ‘94, Gabbi Cervantes ‘94 and Alma Medina ‘92 J.D. ’95 — talked to Casper and Rice. Out of those meetings came an offer from Casper and Rice to form three committees to explore the issues of grapes, a Chicano/a studies major and the construction of a community center in East Palo Alto. Casper and Rice made no concessions on the issue of finding Burciaga another position.

The offer was rejected.

Day two of the strike — Thursday — saw no progress in the talks with the administration, but did see a larger outpouring of community support for the protestors. Some professors taught their classes outside and others gave speeches in acts of solidarity.

Friday brought another intense round of negotiations. An offer made by the administration at 8 p.m. was not much different than the first one — they added in a statement highlighting the importance of Burciaga to the community.

The negotiators decided to take the offer to the members of MEChA that Friday night. The future of the strike would be determined by the most democratic of processes: a simple majority vote.

“We were a little divided — was this agreement good enough?” Silva said.

Ultimately, the group decided that Casper’s offer to form committees to investigate the three issues would suffice.

The negotiations team alerted Casper and Rice to the results of the vote. Casper and Rice then spent the rest of the night tweaking the official wording and language of the agreement. The hunger strike would officially end on Saturday, May 7.

But the official ceremony Saturday morning wasn’t without drama. The protestors seemed to think there was an agreement that Casper and Rice would sign the offer as a kind of symbolic photo op. But Casper balked, claiming no such agreement was made. As the tension of the moment began to rise, Casper and Rice, perhaps sensing some sort of impending public-relations disaster, decided to sign the agreement.

Both sides claimed some victory — even though it was by no means a complete victory for either side.

“I do think there was one bottom line: the University’s processes were respected. [The agreement came out of] reasoned, productive consideration,” Rice told The Daily in 1994. “This is the way to move forward.”

Casper and Rice were unavailable for comment.

The significance

The most tangible long-term impact of the protests can best be found in the creation of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (CCSRE) and the corresponding undergraduate program of Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (CSRE), which includes the Chicano/a studies major. The program — created in 1996 out of the committee’s suggestion — has provided a spot for Chicano/a studies, Asian American studies, Jewish studies, Native American Studies and a general comparative studies concentration.

“It was a big deal for Stanford to establish a Comparative Race and Ethnicities major,” Alvarado said. “For me, the impact was beyond the university; it was national.”

So while the legacy of the protests most visibly lives on in the form of CCSRE, the real legacy lies within the impact the events had on the protestors and the Stanford Chicano/a community.

“We have been re-inspired after learning all the hard work that went into planning and executing the hunger strike,” said Najla Gomez Rodriguez ‘14, a Chicana community organizer. “Learning about the struggles they went through puts our own experience in perspective and gives us all the more reason to work harder in every aspect.”

Catherine Zaw contributed reporting.

Contact Andrew Vogeley at avogeley ‘at’ Stanford ‘dot’ edu.