In 1955, Robert Frank left New York City for the open road. Over the course of the next two years, he traveled across the U.S., taking photographs for his magnum opus, “The Americans.” Cantor Arts Center’s new exhibit, “Robert Frank in America,” is the first show to reunite photographs from “The Americans” with lesser-known works from Frank’s early career.

In every image, Frank captures the diversity of seemingly ordinary Americans and pays homage to the essential weirdness of an individual’s experience. Together, his photos do more: They sketch a portrait of a nation, in which postwar prosperity is the prerogative of a privileged few at the expense of (a majority of) “others.” Frank’s photographs are must-sees for anyone interested in understanding “America” beyond the veneer of its mythology and false promises.

Guest curated by Peter Galassi, former chief curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Cantor’s exhibit includes 28 pictures from “The Americans” and 100 others that did not make the book. The photos are loosely organized by theme, including topics like race, politics, jukeboxes and automobiles.

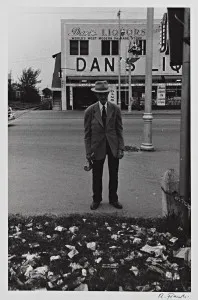

Each picture is a whole world, teeming with with the race and class-based tensions that characterized 1950’s America. In one photo, two middle-aged women – one black, the other white – stare off in different directions. Another picture shows an older businessman in a wrinkled jacket, standing on a street corner in Miami. The ground near his feet is more garbage than grass.

silver print. Gift of Raymond B. Gary, 1984.492.15 © Robert Frank.

Frank’s off-kilter photos – including shots of a River Rouge Plant in Detroit – tend to imbue the cityscape with an eerie, unsustainable air. One picture of a trolley car reflects social hierarchies of the time: The white passengers sit before the blacks, the men before women. As the car hurtles forward, at a slight tilt, the passengers look restless and unsatisfied.

Galassi’s decision to organize the exhibit thematically makes Frank’s social commentary more accessible. A shot taken in Charleston, North Carolina, for example, shows a stoic African American nanny holding a white infant. The child’s skin looks carefully polished, almost incandescent. In the same corner of the exhibit, another photo shows a black baby trying – and failing – to crawl on the floor of a dilapidated café in South Carolina. An enormous jukebox looms overhead. The child is small, the machine menacing.

The first photo seems structured around protecting the white child, almost as a light source. In the latter image, the black child is a figment of the background, nearly rubbed out by shadow. Together, these photos highlight the lottery of birthright in America and the relationship between racial and class privilege. At the same time, Frank’s aesthetic captures the creepy absurdity of these hierarchies, posing the question, “How, exactly, did ‘America’ get this way?”

Frank begins to address this question by satirizing institutions of power in the U.S. He portrays politics as a game played by and for wealthy white men, entirely disconnected from the wants and needs of ordinary Americans. One picture shows a band of identically smiling politicians and identically unsmiling soldiers gathering in Battery Park, New York City. The straps on the military helmets look like muzzles. Behind the servicemen, American flags hang on their stands. Without wind, they are limp and illegible.

When “The Americans” was first published, Frank drew criticism for his pessimism and bitterness – and it’s true that Frank had a gift for capturing Americans alone in a crowd. For instance, in a bar in Gallup, New Mexico, a man in a jean jacket and cowboy hat is a picture of masculine strength, almost excerpted from a Western. Still, he is singled out by a bright overhead light. His would-be peers are out of focus or focusing elsewhere. The man, alone, is the subject of Frank’s photo.

But here is also where Frank makes a counter-intuitive yet saving observation: He shows us that loneliness is what we have in common. We see it in the searching gaze of a cowboy, a bone-thin mother, and an acne-scarred teenager: Everywhere, Americans are looking for a genuinely inclusive community. We long to belong.

Of course, nothing that Frank captured is resolved, really. As Frank said, “It’s a myth that the sky is blue and that all photographs are beautiful.” So when you go to see “Robert Frank in America,” don’t expect closure–but go anyway, because indifference is complicity. Patriotism starts when we tell the truth.

Contact Gillie Collins at gcollins “at” stanford.edu.