When Harry W. “Hunk” and Mary Margaret “Moo” Anderson bought “Lucifer” — one of Jackson Pollock’s prized action paintings and the latest addition to the family’s private art collection — they hung it over their daughter’s bed. Mary Patricia “Putter” Anderson grew up like most girls, hosting slumber parties and fighting the temptation to give Pollock’s painting new “drips.” This privilege — to learn and live among masterpieces — is yours now. In 2011, the Anderson family decided to give its collection to Stanford, and last week, the Anderson Collection at Stanford University opened its doors for the first time.

The Andersons didn’t know much about art at first, but they suffered something of a coup de foudre at the Louvre in 1964. Since then, Hunk, Moo and Putter have devoted themselves to the art of art appreciation, partly by seeking advice from local artists. Perhaps this is why much of the collection is focused “close to home.” Works by Richard Diebenkorn, Paul Wonner and David Park are a welcome reminder that the Bay Area was and is a place for artistic, as well as technological, innovation.

Today, you are one of the first visitors to be seduced by the Anderson Collection at Stanford University. Just inside the doors, a long, gradual staircase takes you up and away. At the top of the stairwell, Clyfford Still’s “1957-J No. 1 (PH-142)” roars before you. The painting is loud and monumental. It works like a bolt of lightning. Swaths of red, blue and white rip across the canvas, shaking you free from the outside world.

What’s brilliant about Still’s painting is also what’s exceptional about the Anderson Collection overall: It is a visceral, aesthetic experience that sweeps you off your feet no matter your background in art or art history. None of this is academic.

And the Anderson Collection feels inexhaustible. Every room is a new theme, including California Light and Space, Funk, Hard-Edge Painting and Post-Minimalism. You pity the tourists who come with cameras and visit only once. They are overwhelmed (delightfully so), scrambling to decode every movement, to mingle with every painting.

As a student, though, you start with small talk but look for something more. You have a chance at romance. Your dry spell is over — prospects are everywhere.

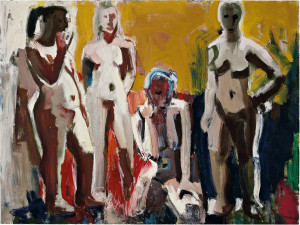

In one room, the Abstract Expressionists are hot commodities. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning draw a crowd. At the heart of their intrigue is the question of gumption; these were artists who tore down conventions in both technique and subject matter. In the aftermath of World War II, they put new emphasis on the process of art creation.

So when you stand in front of Pollock’s “Lucifer,” imagine the painting-in-action. Close your eyes and picture the canvas laid on the ground, as orange, green and grey paint soar through the air. Pollock is before you, on his hands and knees, pouring, streaking and splattering.

Open your eyes. In front of you is Rothko’s “Pink and White over Red.” When you find yourself looking to make out shapes or signs, stop: Accept the emptiness, listen to the silence. This is a painting free of representation. There is only color, humming above the canvas.

But perhaps there is someone else who catches your eye, a stranger that other folks seem to overlook (and you can’t imagine why). What about Vija Celmins’s “Barrier,” for instance? Or “Theophrastus’ Garden” by Terry Winters?

If you find yourself staring at a cartoonish oil painting of an overcoat standing upright, you’re in the company of “The Coat II” by Philip Guston. The jacket is pink and supple, and the foreground is blood-red. It’s hard to distinguish between fabric and flesh, and the painting as a whole feels intensely personal, plucky and seductive.

Now is your chance to introduce yourself. Approach her hat in hand, ready to be vulnerable first. Court her. Set a regular date and return over and over.

If things get serious, plan to visit the family that lives next door: At Cantor Arts Center, you can un-dust her ancestors. They will tell you stories about how she was possible. All of this will take time and attention, but the rewards are life-long. You, too, can have a home in the Anderson Collection.