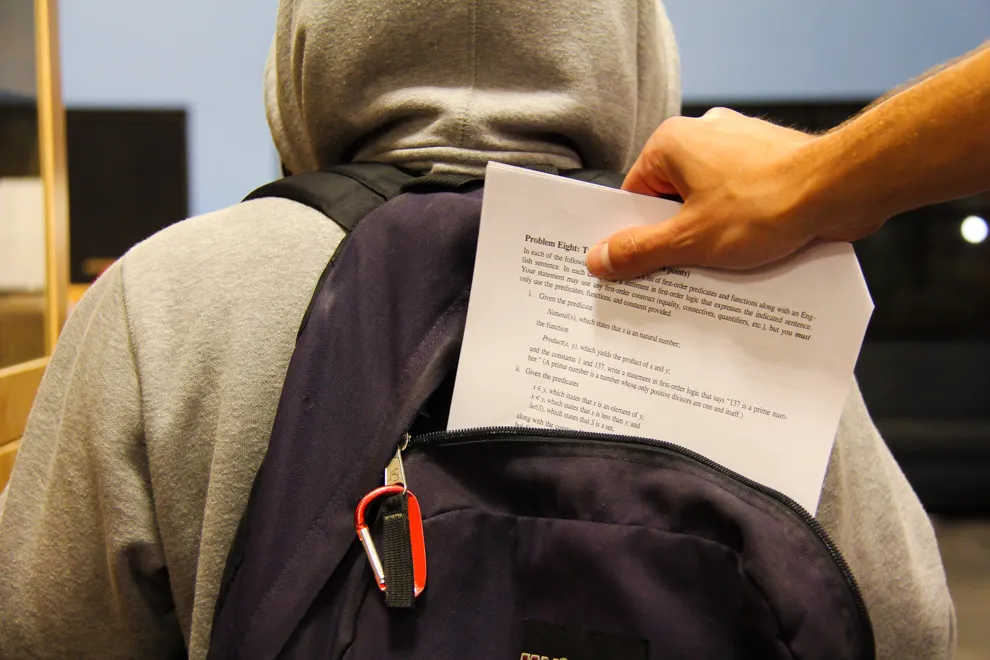

After a quiz on Wednesday, Professor Guenther Walther conducted an experiment in his Stats 60 class to find out how many of his students had cheated while at Stanford.

The purpose of the exercise was to demonstrate a certain technique in probability that allows survey-makers to anonymize individual respondents’ answer choices while discerning the desired information. The result showed that roughly 40 percent of the 86 responding students had cheated while at Stanford.

According to Susan Fleischmann, director of the Office of Community Standards, 83 students were found responsible for Honor Code violations through Stanford’s Judicial Process last year.

Considering national data on the Open Education Database along with information collected at Stanford, the number of students who break the Honor Code and go unpunished is bound to be much higher.

Student responsibility

Stanford’s Honor Code was written by students in 1921 and founded on the principle that students, not the administration, hold primary responsibility for protecting academic integrity at Stanford.

Text in the honor code states that students promise to “take an active part in seeing to it that others as well as themselves uphold the spirit and letter of the Honor Code.”

Yet many like Zane Hellmann ’16, a former ASSU senator — who has seen peers break the Honor Code during a test — turn a blind eye to cheating.

“I think there are a lot of people that think, I’m not going to do that, but if that’s what they want to do, that’s fine,” Hellmann said.

This line of thinking is problematic for the system of collective student ownership established in the Honor Code.

“It’s not good enough to say: I won’t cheat, but others have free range to cheat,” said Eamonn Callan, professor in the Graduate School of Education. “That is simply an incoherent social practice.”

Computer science professor Eric Roberts explained that an Honor Code system does not work as well at large schools like Stanford as it does at smaller schools that are more close-knit. A 2010 study presented in the Faculty Senate found that 55 percent of undergraduate students and 62 percent of graduate students would report an infraction by a classmate.

At the time, philosophy professor Kenneth Taylor criticized the reported numbers, saying that they might disguise even more prevalent lack of reporting and that the University needed to “get angry” about the culture of apathy among students.

Even so, Roberts does see an advantage in Stanford’s Honor Code over administrator-run models of academic integrity at peer institutions, namely that students have more investment in the process.

Lack of full understanding

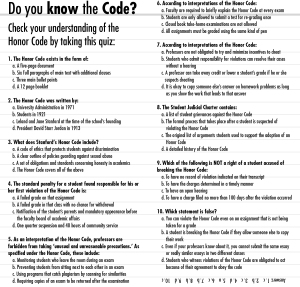

Yet even with the responsibility falling on students to uphold academic integrity, John-Lancaster Finley ’16, chair of the ASSU’s Administration & Rules Committee, explained that students often have a fundamental misunderstanding of what the Honor Code is.

“People really see the Honor Code as a University policy, and it’s not a University policy,” Finley said. “It’s an agreement between the students and the University.”

Hellman said that he thought most students weren’t even aware of the judicial process’s details, and that he would not have been if he hadn’t served in the Senate.

The standard sanction for a student who has committed their first violation of the Honor Code is a one quarter suspension and 40 hours of community service, according the Office of Community Standards website. Multiple infractions will lead to a three quarter suspension and 40 additional hours of community service.

The need for better education on what the Honor Code entails is in part due to the fine lines students face on a regular basis: Where is the line between collaboration and using a friend’s intellectual work? How does one cite sources of inspiration, rather than sources of textual evidence or specific ideas, in papers? What is the situation when assignments don’t count for a grade?

“I think it can be difficult to tell when something’s a violation,” Kay Dannenmaier ’16 said.

Hellmann explained how he once stumbled into violating the honor code in a PowerPoint presentation.

“I didn’t include a reference slide at the end,” he said. “So it seemed like everything in the PowerPoint was my creation.”

“I’m sure there are a lot of people that violate the Honor Code without knowing it,” Hellmann added.

Freshmen are briefed on the Honor Code by the University Provost at one of the all-freshmen New Student Orientation events.

“They gave us a flyer and kind of told us what it is about,” Anna Zeng ’18 said of the event. “I just kind of vaguely remember…but it was about being a good person.”

Hellmann suggested that students be taught the Honor Code by fellow students in a residential setting, rather than at an all-class meeting during NSO. Sean Stanko ’15 recommended that Honor Code education be incorporated into Thinking Matters courses for freshmen.

Leadership’s response

Ross Shachter, member of the Board of Judicial Affairs and a professor in MS&E, emphasized that education was a big focus of the board last year and that the board will continue to encourage students to take ownership of the Honor Code and fulfill their obligations to it.

The board will also continue to encourage faculty to play their own part in upholding the Honor Code. Shachter described how, in some cases, faculty are tempted to bypass the judicial system.

“The faculty have the responsibility if they become aware of an honor code violation or suspected violation…to go through the process at the Office of Community Standards,” he said. “I think there are some faculty who are tempted to short circuit that process.”

According to Finley, the ASSU wants to start a discussion among the student body that will produce amendments to the Student Judicial Charter this year.

He admitted, however, that the ASSU would have to sort out a lot of their funding issues before they can take on something so broad.

Contact Erica Evans at elevans ‘at’ stanford.edu.