In September, Stanford’s English department launched the digital humanities (DH) minor, a program which allows students to use digital tools to enhance their understanding of the humanities and generate new questions for innovative research.

Students in the minor choose between one of three focuses, or clusters: geospacial humanities, text technologies or quantitative textual analysis. Each track has a corresponding introductory class that is partly method-based but also exposes students to the larger themes of the digital humanities.

The minor, which was proposed in April 2014 and approved last May, requires students to complete 20 units, including one core class of five units and five other courses with a minimum of three units each. Some of the specific courses provided include Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages 122: “The Digital Middle Ages,” English 150: “Poetry and the Internet” and English 180C: “Technologies of Enlightenment.”

Professor of English Elaine Treharne, who co-directs the digital humanities minor and directs the program’s text technologies cluster, indicated that profound student interest in the field was one of the main reasons for the minor’s creation. During January 2014, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences held a small symposium on campus where Treharne and a few of her colleagues gave speeches about their work.

“At that point we realized we have all this expertise and all these innovative, ground-breaking projects that really benefit research and Stanford’s various articulations of that research, but it doesn’t benefit the undergraduates in a cogent way,” Treharne said.

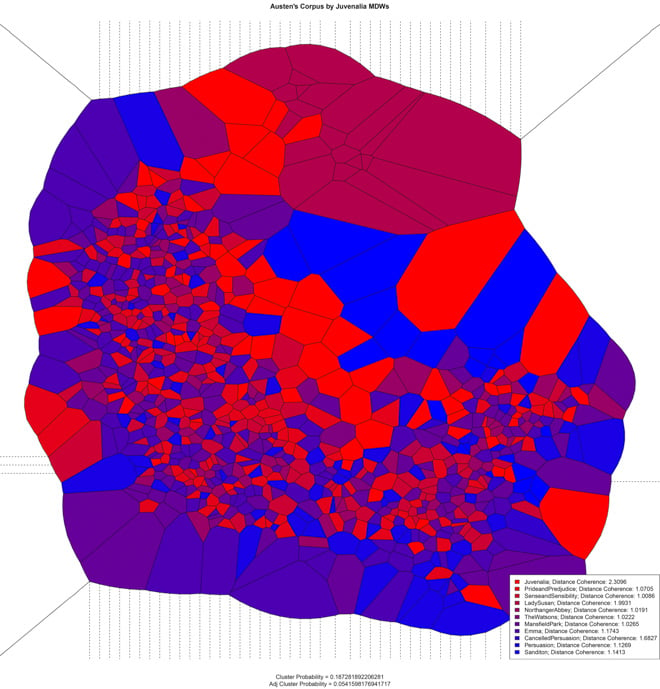

Mark Algee-Hewitt, assistant professor of English and director of the quantitative textual analysis cluster of the minor, shed further light on the topic.

“The minor came about because the digital humanities is an area at Stanford where a lot of interest is already happening,” Algee-Hewitt said.

“The Center of Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA), the Literary Lab and the Stanford University Libraries are very active in researching and working in the forefront of this new emerging field,” he added.

Algee-Hewitt explained that prior to the creation of the minor, undergraduates were getting exposure to the digital humanities solely through research opportunities and various courses related to the digital humanities’ goals.

Treharne and Algee-Hewitt, along with linguistics lecturer Sarah Ogilvie and associate professor of history Zephyr Frank, worked to create the digital humanities minor, which gives students a framework to bring together these courses and opportunities into a coherent program.

According to Treharne, about 20 students have expressed interest in the digital humanities minor so far, but the process for declaring has not yet been finalized online.

For Mirae Lee ’17, the new digital humanities minor was exactly what she was looking for in a degree. During her sophomore summer, Mirae joined the Literary Lab, which ignited her interest in textual analysis before the opportunity for a class in the subject was even available.

“For a long time, I was considering the CS+X joint major program, but there wasn’t enough overlap between taking English and CS classes through this program,” Lee said. “The digital humanities classes I have pursued now are very emphatic on the connection between my interests.”

At first, Lee was concerned that performing quantitative analyses of texts would destroy the beauty of reading them. However, once she obtained a deeper understanding of the process of textual analysis, she began to view it as simply another tool through which to appreciate literature.

“The DH minor teaches humanities students how to use digital tools in ways that enrich their primary humanities specialism,” Ogilvie said.

According to Algee-Hewitt, the research in digital humanities has been vast and innovative. He explained how analytical methods were used to deal with “messy” humanities problems.

For example, the head of Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Michael Burger, utilized the methods developed for examining 19th century Victorian novels in order to examine Supreme Court case decisions on environmental law.

Burger assessed the difference between Supreme Court decisions that were viewed as environmentally protective and those that were not. The language differences he measured pointed towards the way the Supreme Court functions while making decisions.

Through the Global Currents project run within CESTA, students and professors are currently analyzing 100,000 images of 12th century medieval manuscripts. Using feature modeling, a computer is being trained to read the way that information is being laid out in these manuscripts, explained Treharne.

“Big questions such as how we recognize what constitutes a text, how we recognize different components of texts, how we recognize where books were made and what materials were made in their production are all being answered,” Treharne said.

“This tells us the expectations manuscript makers had of their readers,” she added.

Through this and various other projects, students in these digital humanities classes are participating in real, ongoing research that in many cases hasn’t been done before.

“The minor in DH will be a bonus to any humanities graduate’s CV because it will signal that you are able to engage seriously in your field while also applying to the it the latest innovative and cutting-edge digital methods and tools,” Ogilvie said.

Contact Pascale Elisabeth Eenkema van Dijk at pevd ‘at’ stanford.edu.