Upon its release in 1966, Gillo Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” became an instant art-house sensation and garnered three Academy Award nominations. Since then, it has been both the subject of controversy and commendation. The film was banned in France in the 1960s because of its graphic violence and screened at the Pentagon in 2003 because it was deemed to be a realistic representation of the kind of guerilla warfare American troops would face in Iraq. Fifty years after its original release, the film is returning to theaters in a new restoration helmed by Rialto Pictures. Now, more than ever, films like “The Battle of Algiers” are grippingly, crucially important.

On the surface, “The Battle of Algiers” is a war film that concerns the conflict between Algerian guerilla fighters, striving for independence, and the French army, struggling to maintain its grip on the city. Algerian independence had become a cause célèbre in France in the 1960s as leftist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre rallied to put an end to colonialism. The film is based on writings by former National Liberation Front (FLN) guerrilla fighter Saadi Yacef. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) even once believed Pontecorvo, a Communist sympathizer, was a Soviet spy. It would have been relatively easy for Pontecorvo to make a film decrying French abuses and championing Algerian independence.

Yet what surprises me about “The Battle of Algiers” is it is not pro- or anti-Algerian independence. Pontecorvo refuses to take a side on the conflict. We observe both the brutal torture techniques of the French and the meticulously planned terror-bombings of the Algerians. We see the shock of the French elite when their high-end country clubs become the sites of gun battles and the grief of an Algerian mother when she learns that her son has been arrested by the French police. Pontecorvo does not give us a protagonist, an antagonist or even a main character, instead drawing our attention to the diverse groups of people involved.

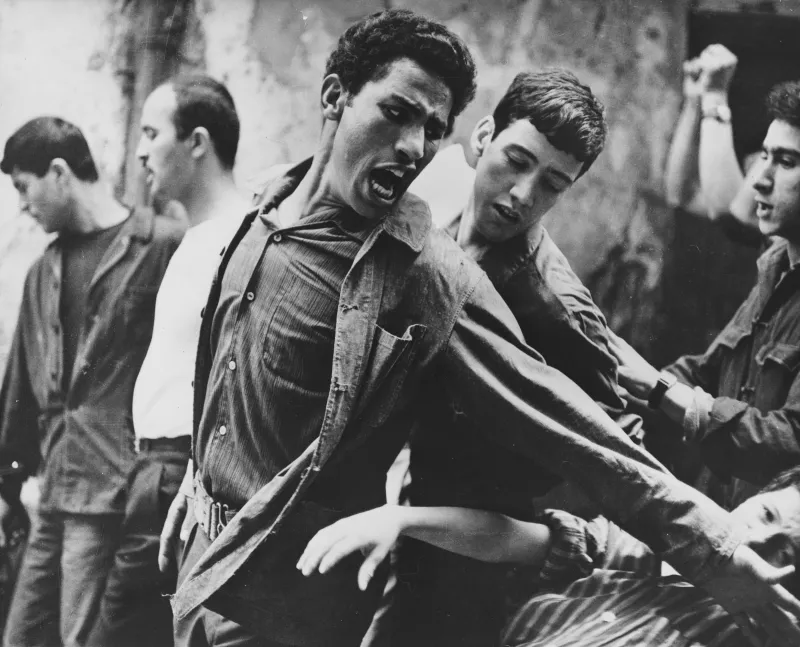

I am also stunned by the astonishing realism of “The Battle of Algiers.” Although the film does not contain a single frame of documentary footage, the vitality of Pontecorvo’s Algiers and the emotion he elicits in close-ups from his actors makes one feel as if they are watching newsreel footage from the late 1950s. Pontecorvo’s camera weaves in and out of crowds, his images become obscured by the smoke of battle and his soundtrack (with a score by Ennio Morricone) is not always in sync with the visuals on screen. His mise-en-scène is often cloaked in the drab grey of the Casbah, and nothing is black-or-white in Algiers. This degree of realism is astonishing.

Still, the film’s realist aesthetic is no mere gimmick. Pontecorvo does not shed light on all the players or details of the conflict, but his realism conveys the pandemonium and brutality of the gruesome conflict. It is often unclear who has the upper hand. The torturers can become the tortured, and Pontecorvo shows us that God is on no one’s side.

Furthermore, the battle is not a beginning or an end in and of itself. In these complex conflicts, even small decisions can have great ramifications. Colonel Mathieu, the leader of the French soldiers, warns that if France is to stay in Algeria, the French must be ready to accept all the consequences of their actions — ramifications that include continued terror, violence and bloodshed. The French can eliminate all the key players in the FLN, but they cannot destroy the Algerian desire to be independent.

Since the release of “The Battle of Algiers,” the United States has been involved in long, costly wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. The failure of American troops to bring peace and establish democracy in these regions has often been ascribed to their inability to match the passion or organization of guerilla fighters. As we look back on these conflicts, Colonel Mathieu’s comment seems eerily resonant.

But the Algerians too must accept the consequences of independence. At a crucial point in the film, a guerilla leader tells a fellow soldier that “it’s hard enough to start a revolution — even harder to sustain it — but it’s only afterwards, once we’ve won, that the real difficulties begin.” Similarly, the Arab Spring failed to live up to its promise of bringing democracy to North Africa. Activists in Egypt and Libya succeeded in toppling despotic leaders but could not deal with the real difficulty of establishing democracy on the remains of an authoritarian regime.

The title of the film is deceptively simple. “The Battle of Algiers” is an armed conflict in which combat is waged in bustling cafes and fashionable jazz clubs. Still, in a sense, “The Battle of Algiers” ends before the real battle begins — the struggle to establish something durable on the foundations of war and violence. In another sense, “The Battle of Algiers” is not a traditional battle at all. There are no victors but only losers as both the French and Algerians continue to advance a cycle of violence. Fifty years old, Pontecorvo’s nihilistic vision of war seems as real and as timely as ever.

Contact Amir Abou-Jaoude at amir2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.