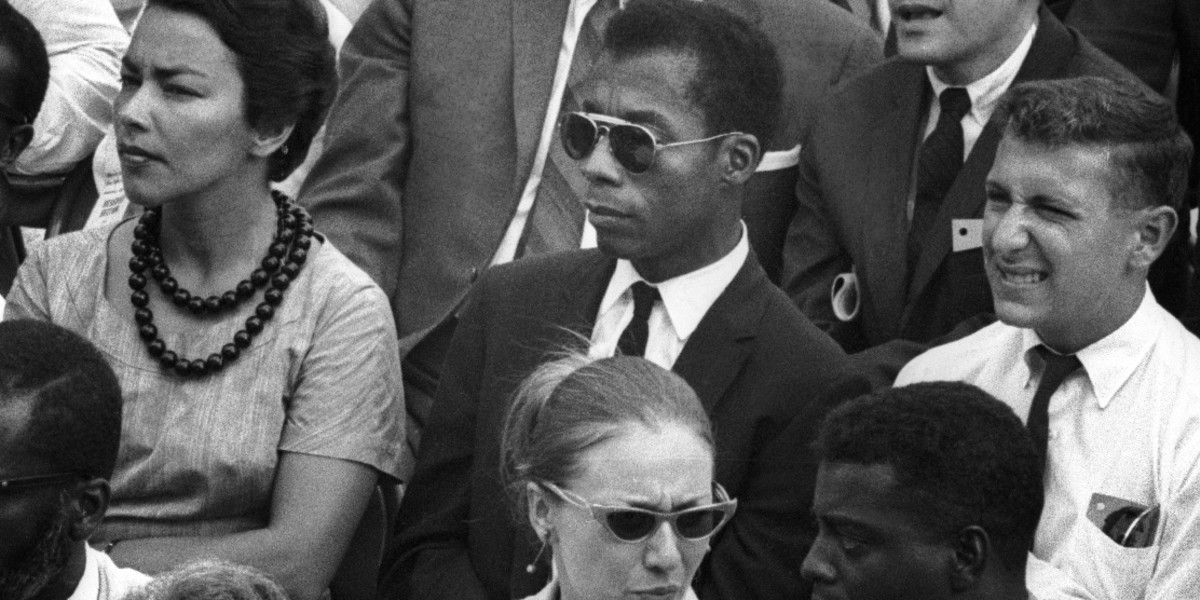

At the time of his death in 1987, black writer and activist James Baldwin left an unfinished manuscript entitled “Remember This House” detailing his personal experiences of the deaths of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Now, nearly 30 years later, Raoul Peck brings this very manuscript to life with the Oscar-nominated documentary “I Am Not Your Negro.” In 95 minutes, Peck transports you backwards and forwards in time, all the way from the Civil Rights Movement to present day, melding together two frightening realities and showing us that they’re really not all that different.

Baldwin’s perspective is rather unique. Baldwin was not a member of the NAACP — nor was he a member of any Christian congregation or the Black Panthers. Instead, he wrote ever so candidly about what he knew: personal experiences rather than doctrine.

As a young boy, Baldwin had a white, female teacher who was so kind that he grew to convince himself that he could never truly hate white people. Yet, he is undeniably persistent in what he believed in, at least at the time of writing — he essentially has little hope for improved race relations in the United States. And when Peck weaves in footage from present day protests, arrests and police standoffs, it’s a tough image to face. Peck’s images remind us that while much has changed on the surface, very little has changed underneath. Have we really changed all that much since the time when Baldwin experienced the losses of civil rights leaders who were also his friends? Should we, as viewers and as Americans, also be as hopeless as Baldwin?

I, for one, used to think that I still had reason to have hope. But with what has happened over the course of 2016, including the public unleashing of buried racist sentiment, I now really struggle to disagree with Baldwin. Peck makes use of a wide variety of archival footage of Civil Rights history — film and television, newspaper clippings and headlines, images of white power and supremacy rallies — as well as footage of current conflicts and events. By stringing together such a wide collection of material, Peck makes the pervasive point that what we’re experiencing today is obviously not new but is also part of a simmering resurgence of white nationalism that has been hiding in plain sight.

To me, Peck’s message was beyond what Baldwin wanted to target about being helpless in the grand scheme of events. At the time that “Remember This House” was written, Baldwin would have seen the terrors that surrounded him. But when paralleled with what’s happening today, Peck both reaffirms Baldwin’s fears and ultimately makes the silent conclusion that we’re basically no better than we were half a century ago. Through historical imagery of white supremacy rallies, some individuals as young as probably six or seven, screaming at black students and proudly waving Swastika-emblazoned posters, Peck makes it alarmingly clear that it’s quite ridiculous that we still call this faction of society the “alt-right” rather something more along the lines of neo-Nazism or white supremacism.

So much media coverage nowadays relies on the idea of resistance of the now extremely conservative, white nationalistic government, and although I can’t speak to Peck’s true intentions, “I Am Not Your Negro” very deliberately plays devil’s advocate. In “I Am Not Your Negro,” Peck argues that maybe we as a society can’t really undo what is already hiding beneath the surface. And that within itself is a scary thought.

Documentaries typically have a very targeted audience — those that, well, like documentaries. Despite his recruitment apparently partially for the sake of publicity, Samuel L. Jackson makes for a solemn, somber narrator whose voice completely suits the emotional tendencies of the film. But for a film that has so much relevance to issues of today, I found it a little hard to see how general audiences — who tend to ignore everything but action, adventure and spectacle-fueled scenes — might respond to the tenor of this film. Nevertheless, Baldwin’s words are beautifully crafted, and his writing pieced together ever carefully into a documentarian masterpiece.

Contact Olivia Popp at opopp ‘at’ stanford.edu.