Stanford graduate students in a biodesign innovation class recently underwent a series of emotionally frustrating hospital simulations to deepen their perspectives on medical challenges.

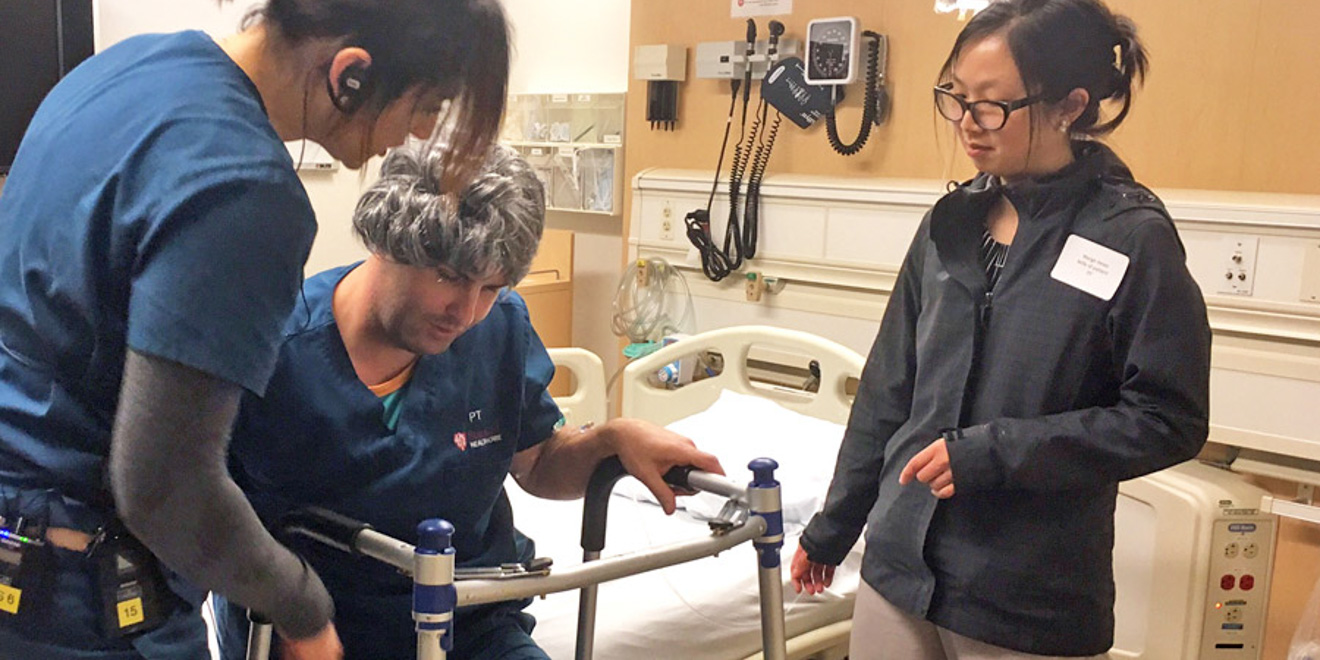

“Biodesign Innovation” takes place over two quarters: This quarter’s “Concept Development and Innovation” course follows winter’s class on “Needs Finding and Concept Creation.” In the simulations, students experienced different roles in scenarios involving an emergency room, a patient room with a woman at the brink of death and a physical therapy consultation with a woman deciding whether she could continue to care for her mobility-impaired husband at home. The students said they ended the class feeling unsettled and confused, obstructed by the financial and ethical challenges that stood in the way of decision making.

The simulations were structured to encourage problem solving through a needs-driven approach at the foundation of the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign: The tactic emphasizes thoroughly understanding a problem before brainstorming solutions. Grad students in the biodesign innovation class, tasked with developing devices that take advantage of the latest technological advances in medicine, experienced the needs-driven approach to gain a perspective on healthcare delivery problems that surpass the purely technical. The need-focused strategy seeks to account for all stakeholders in a particular situation in order to avoid creating products that are unmarketable and too narrow in design.

The simulations developed used Stanford Medicine’s Center for Immersive and Simulation-Based Learning (CISL) to reproduce accurate versions of reality. The center, which usually gives medical students and professionals the opportunity to improve their skills in realistic settings, has just begun to branch out to other users.

Alexei Wagner, clinical assistant professor and assistant medical director at Stanford’s department of emergency medicine, designed the simulations. Each one featured real doctors, mannequins with staff-controlled voices and actors posing as patients.

“If you’ve never had the chance to observe health care in this way, the experience can be a little overwhelming,” Wagner told Stanford News. “But giving [students] this kind of first-hand experience, even in a simulated environment, is a great way to inspire students about the role they can play in helping make the care experience better for patients and the providers who serve them.”

For the biodesign innovation students, the simulation initiative provided industry insight closer to that of the doctors and engineers enrolled in the Biodesign Center’s year-long fellowships. While graduate students encounter time constraints and privacy concerns that prevent hospital immersion, the simulations — described by the participants as “chaotic,” “humbling” and “complicated” — allowed a more first-hand perspective into medicine.

This perspective informed the students’ projects, some of which grew out of the simulated scenarios: For example, some class members’ concerns about older patients’ risk of falling led them to develop an assistive walking device.

Contact Susannah Meyer at smeyer7 ‘at’ stanford.edu.