It’s not often you get the chance to see a Nobel Laureate in concert. So when the opportunity presented itself – in the form of Bob Dylan playing three shows in late April, at the small, ornate London Palladium during my quarter abroad at Oxford – I took it.

I arrived early in my Dylan t-shirt and found in my seat in the upper circle as audience members trickled in, wearing shirtsleeves and dresses. I’d felt vaguely anxious all day. Ordering a pint of ale from the bar, I realized it was most likely out of a kind of meeting-your-heroes sense of trepidation. Would these few hours live up to the lifetime’s worth of myth and meaning I’d built up around the man behind the microphone? I’d have felt almost more comfortable having Dylan remain a legend.

As the lights dimmed, I wondered what the show would sound like. Would he play mostly jazz standards or more familiar songs from his own repertoire? Most likely he’d play whatever he wanted, with none of it sounding quite like it did in the studio. I had the strange sense that he might begin with “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’,” the dramatic opener to 2009’s “Together Through Life.”

I was wrong – though he did play that song a few minutes into the show. In an early sign of what would prove to be a night rich with a sense of relevance, the show opened with a man striding onto stage right carrying a guitar, wearing a hat – not Dylan, though I thought so at first, my heart trembling. Dylan entered stage right and walked to the piano, a strange place to see him sit in light of his prior life as the young man with a harmonica and guitar. He started to sing the words to “Things Have Changed,” a cynical, bleakly contemporary 2000 single. “People are crazy and times are strange / I used to care but things have changed,” the chorus goes. A shrugging apologia for his lukewarm reaction to being awarded the Nobel? A nod in the direction of critics who’ve said he’s lost his political sting? The song reminds me of something that might be sung in a time and place of lawlessness or many-sided war – a song from Machiavelli’s Italy, Thucydides’ Greece, or, perhaps, Cormac McCarthy’s Texas-Mexico border. In a year when traditional institutions, alliances and truces seem to be fraying from North Korea to Britain, Dylan’s looking to the east, and he’s seeing the clouds rolling in.

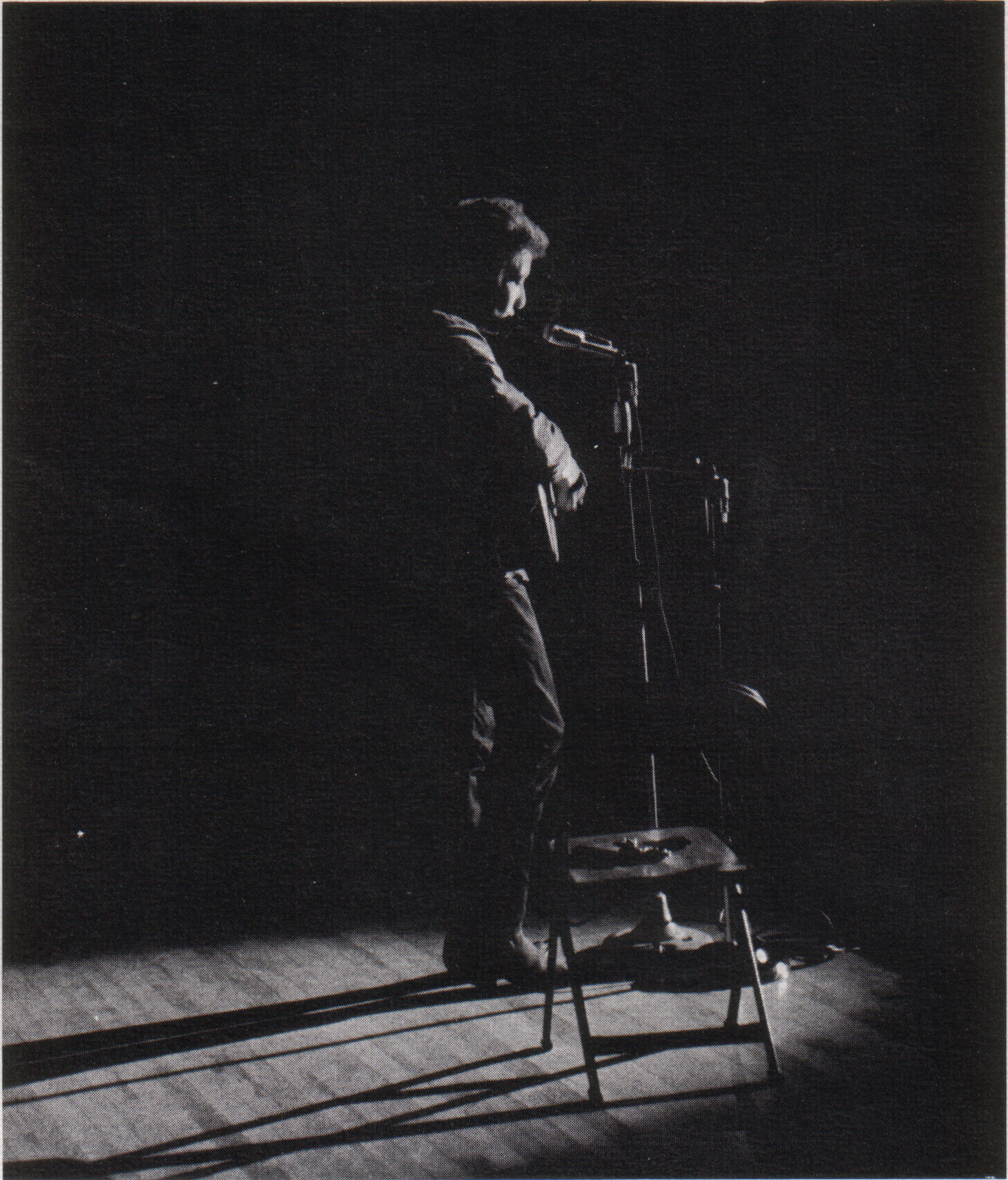

Dylan would sing an old song (pre-1980), a new song (post-1990), then a jazz standard. The band around him played a robust, swaying, sort of folksy guitar and violin sound, reminiscent of Ray LaMontagne or the accompaniment on “Soon After Midnight” off 2012’s “Tempest.” The lights changed from stark-from-high-above to warm and close on the jazz standards. Dylan would stand up from the piano in his sparkly suit and black-and-white tap shoes, take the microphone stand so that one leg of its tripod rested on the ground behind him, and sing with his legs bowed wide apart, taking a single step backward or forward from time to time. His singing on the jazz standards – crooning, it must be called, though that word seems to stick in the throat describing the sermonizing nasality of Dylan’s voice – was, remarkably, exquisite. There was pathos crammed into the final syllable of “Autumn Leaves,” Dylan holding the word “fall” in a sorrowful, quiet quaver as the warm, gentle sound of the accompaniment died out around him.

Now, as always, the beauty of Dylan’s work exceeds (or, more likely, is all bound up in) his insistence on confounding expectations and imploding anyone’s theory about his work and its significance. Critics haven’t missed the irony in Dylan’s latest habit of recording covers just as his lyricism is crowned with literature’s highest laurel or in his adoption of the songbook and the accouterments of an epoch in American music and culture that he played a major part in demolishing. I’d had a hard time finding the significance in his covers, but on “Autumn Leaves” it seemed to click. A classicizing tendency, an acknowledgment of his own waning season.

However, either Dylan’s vocal capacities have weakened regarding the louder notes of his rock repertoire, or he has become disenchanted with some of its beauty. He sang many of these songs to the same notes – as if the verses on every song were the verses of “Long and Wasted Years” from “Tempest” (which, notably, also featured on the setlist). High note at the beginning of the verse, mostly the same note through the middle of the verse, low note at the end. This formula takes some of the energy out of Dylan’s beautiful earlier songs, I noticed during an unmoving “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” However, it also encourages the audience to seek beauty in new places in his songs. With that inimitable nasal bray gone from the final two notes of the opening line to the classic “Desolation Row,” (“They’re selling postcards of the hanging”), the great flourish came instead at the end, when Dylan sang the final line (“Don’t send me no more letters, no / Not unless you mail them from Desolation Row”) ascending and then descending down the octave, which lent the song a sense of an ending and a tongue-in-cheek pompousness that the 1965 recording lacks.

The band played a galloping rendition of “Highway 61 Revisited” as Dylan sang, “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son!’” with all the fabulistic, decadent vision of late 1965. As the chords of “Tangled Up In Blue” played, tears sprang to my eyes. Dylan did great justice to that song with its tenderness towards remembered moments both of connection and of missed connection. “They never did like mama’s homemade dress,” he sang, describing how the song’s narrator suffers when his lover’s parents disapprove of his own family.

“Tempest” and “Highway 61 Revisited” featured most prominently in the catalog of earlier songs Dylan played. The choice of these two albums is significant. “Highway 61” displays all the Beat madness of the 60s, Dylan’s final abandonment of folk for good, a statement that the old order was dead and the new one not yet formed. “Tempest,” on the other hand, is dark and bloody, displaying Dylan’s capacity for callousness and violence in levels not seen since “Idiot Wind” off of 1975’s “Blood on the Tracks.” It’s a fantastic album and one I was not at all chagrined to see so well represented on the night, making up nearly a quarter of the setlist. “Two-timin’ Slim? Who’s ever heard of him? / I’ll drag his corpse through the mud,” Dylan growls on “Soon After Midnight,” a cold, visceral threat embedded in an otherwise tender, jazz-standard-esque love ballad of sorts. The same song also features a Dylan staple in its last line, namely the cruel, backhanded confession of love: “When I met you, I didn’t think you would do / It’s soon after midnight, and I don’t want nobody but you.”

I noticed also in the songs Dylan sang from “Tempest” that night more than other times a sense of memento mori. On the burlesque “Duquesne Whistle,” a song steeped in the early twentieth century and, perhaps, Dylan’s own distant past in rural Minnesota, he sings of a train “blowin’ like she ain’t gon’ blow no more.” A burr in his voice on the final syllable seemed to point the meaning of the phrase back at himself. It’s more explicit on the marching “Early Roman Kings”: “I ain’t dead yet,” Dylan grins, “My bell still rings / I keep my fingers crossed / like the early Roman kings.” Visions of death and visions of history combine. Again, I think of a time of barbarism and strange rituals, of blood and darkness and mystery. Dylan’s invoking of the early days of Rome is right on target: A strange time, described by Livy in his histories – the age of Tarquin and Numa, an age before reading and writing; of mysterious rites that, when performed incorrectly, lead the gods to slay with bolts of lightning the men who profane them.

Dylan did not speak a word during the entire performance. After “Autumn Leaves,” he and the band left the stage, to return after the audience called for an encore. The band played two more songs, both fascinating choices. First was a nearly unrecognizable “Blowin’ In the Wind” – the last vestige of Dylan’s old, old millenarian optimism, offered perhaps as nothing more than a cruel joke at the expense of hopes for peace in a world of men beginning once more to tear at each other’s throats. Second, and finally, was “Ballad Of A Thin Man,” that strangest of songs from “Highway 61.” Most famous perhaps for its marking of a high-water point in Dylan’s absurdist songwriting style (including, as it does, the rather unfortunate line “Now you see this one-eyed midget / Shouting the word ‘NOW’”), and a surprising choice of finishing song, I considered it as a political song for the first time that night.

The song mocks the titular thin man, who despite thinking himself clever, finds himself at a loss as a gallery of social outcasts torment him, trying to convince him he’s one of them. “Because something is happening here, / But you don’t know what it is / Do you, Mister Jones?” the song’s chorus insists. Is the thin man an establishment politician – a moderate Republican, a Clintonite Democrat, a Europhile Tory – confounded by the gallery of sneering populists? Or is the thin man Donald Trump, convinced of his own superiority but tormented by judges, his own party, and a persistent inability to quite grasp exactly what that “something” that’s happening is? The line itself sounds almost like something he’d say.

Regardless, the song’s indictment, maybe originally meant to criticize the 1960s intellectual who finds himself unable to understand the monstrous new evolutions of American culture (like, perhaps, Jack Kerouac, betrayed by the counterculture movement he helped found), applies now to all of us as affiliates of Stanford, card-carrying members of the cosmopolitan intelligentsia, all of us who failed to apprehend, and later to understand, the monstrous surge of fury of 2016, the grotesque figures of the new populism. It is not an optimistic note to end on.

Finished with the song, Dylan stood up from the piano and stood with the band in front of their instruments. They did not bow or gesture to the audience but merely stood there, like workers looking upon a day’s work, proud; or else like men facing a firing squad. The light fell on Dylan’s hat, his face hidden in shadow. One could barely make out his curved mustache which further concealed that cruel mouth. Did I see a glimmer in one eye? He turned, and the men of the band walked out behind the curtain. The lights went on. I wandered like a dreamer down Oxford Street towards the bus back to Oxford.

Contact Nick Burns at njburns ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Updated June 6, 2017: An earlier version of this article mistakenly claimed that “Things Have Changed” was released in 2006. It was released as a single in 2000.