The Georgia O’Keeffe exhibit at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) seeks to explore more than her legacy as an artist. Although distinctly known best for her many paintings of flowers, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) was more than just a modernist artist. In fact, as the exhibit carefully describes, these famous flower paintings quickly became the infamous paintings that we know as a result of a public push to sexualize her work. Even as she vehemently tried to dispel these myths, this attribution of connotation to her work became engrained in her artistry, sadly never able to be removed. She constantly stated that flowers were just flowers and colors were just colors. Her longtime partner and eventual husband, artist and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), often took and created intimate nude photos and portraits of her as part of his own work. Even if these remained precious to him as personal representations of his love for O’Keeffe, the public couldn’t keep its hands off and flocked to enshrine her as the sexualized, misunderstood being, only truly seen through her cryptic paintings of flowers.

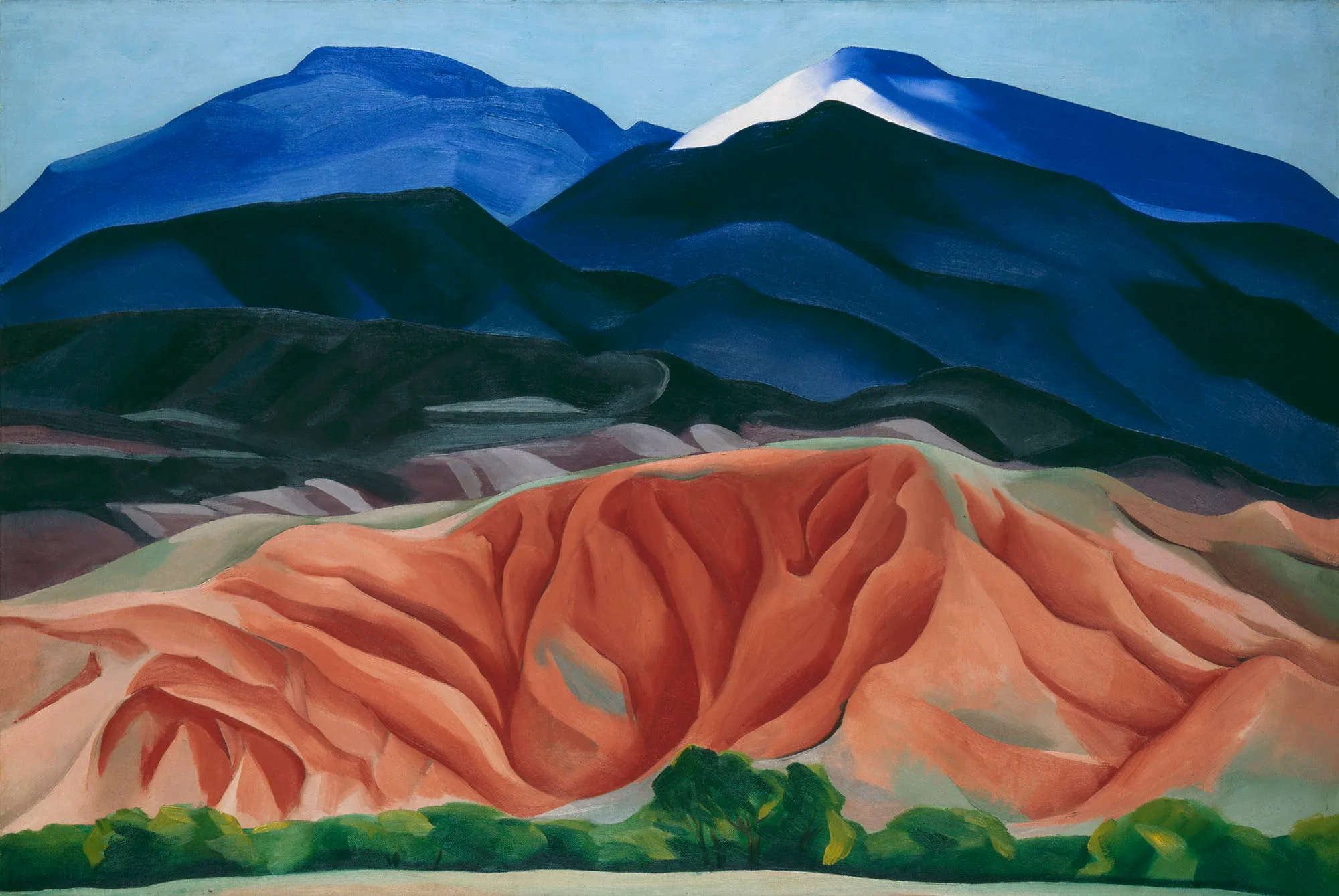

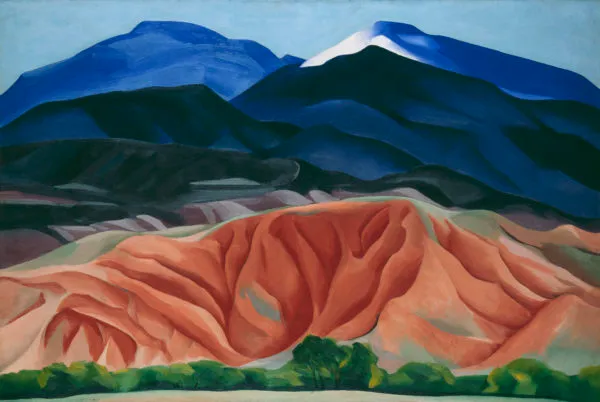

Both Stieglitz’s photos and O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are displayed at the AGO along with many other paintings from O’Keefe’s other periods. Her many lavishly, contrastingly colored landscape portraits of the American Southwest portrayed her fascination and wonder with the region. Although always in love with New York, something about the region spoke to her—a sense of solitude unattainable in New York, yet unexplainably perfect. Yet even O’Keeffe’s paintings of animal skulls—her foray into abstractionism—became twisted into what the public wanted to see. People saw her as a loner, almost some kind of mystical being, and O’Keeffe felt as if she had to shift from abstract paintings to more realistic, as even her works depicting animal skulls that she found out in the desert could no longer be presented without some kind of manipulated imagery of pent-up lust or romanticized sentiment.

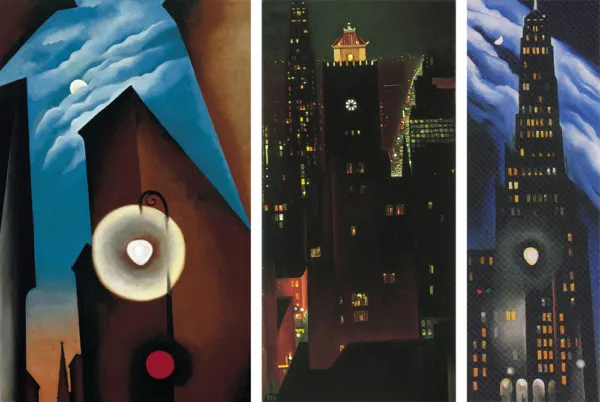

Even as she aged, O’Keeffe as “the artist” became a figure that everyone knew. She was on the covers of magazines and the subject of articles, always associated with her life in New Mexico. Her paintings of the landscape and the natural features became closely associated with the reclusiveness of her life once Stieglitz passed. I found the exhibit immensely frustrating yet immensely eye-opening, especially with Stieglitz’s work placed alongside O’Keefe’s. The flowers obviously displayed first, then some intermediate works of Stieglitz along with O’Keefe’s New York paintings with a detailed description of her high-society artist life in the city. Later, O’Keefe’s lesser-known landscapes and more abstract works topped off the exhibit, almost but not entirely chronological.

I overheard a conversation by two middle-aged men, presumably educated in at least some sort of art history and background, as I walked through the exhibit. They read a short description that told of how O’Keeffe did not want her flowers to have any extraneous connotations, yet proceeded to laugh and ask rhetorically how the paintings clearly portrayed a woman unable to express her “clear femininity” other than through her work. As a woman and an artist, I still could not help but be grossly transfixed and eerily disgusted by O’Keeffe’s continued legacy as a sexualized symbol. Although we may not immediately associate the sexual symbolism with her work that art critics did, it still raises a troubling question. Like public perception of celebrities and artists today, we very rapidly jump to judge individuals based on what the masses say. With the influences of Stieglitz—a male figure who did not necessarily completely define her career—O’Keeffe was quickly brought up to the big leagues amongst the New York elite and avant-garde artists to whom she would be forever tied. Who’s to say how O’Keeffe may have been seen without the looming eye of critics to constantly analyze her precious flowers, mix her personal life with her artistic one or take even her own statements with a grain of salt.

How can we trust to continue beyond this thin veil of public shadow casted upon art? It may be impossible to unlink the inextricably linked artist from her art, but it’s aghast to think that we as a society cannot even trust the artist’s own words. This uneasily feeling lingered with me throughout the entire exhibit, even as I was astounded by her many natural landscapes that far exceeded her famous flowers in depth and vibrancy. I couldn’t shake what O’Keeffe’s legacy means for artists today—a constant reminder of the fact that we are judged, especially by our own actions, statements and even accidental associations. It’s something that we sadly and frustratingly may never be able to get over, but certainly need to try, even for the sake of honoring the wishes of individuals who just want to be taken seriously, not solely seen in the light of their male counterparts.

The Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective exhibit is at its only North American stop at the Art Gallery of Ontario until July 30.

Contact Olivia Popp at opopp ‘at’ stanford.edu.