Stanford Medicine will open a new Center for Definitive and Curative Medicine (CDCM) to treat people with genetic diseases using stem cells and gene therapies. The center is a joint-initiative with the school of medicine, Stanford Health Care and Stanford Children’s Health.

Maria Grazia Roncarolo, MD, who is the George D. Smith Professor in Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, will direct the center, located within the Department of Pediatrics in Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. Roncarolo said the same physician-scientists developing the drugs will treat patients, expediting the process of finding appropriate and precise treatments.

“We will use the discoveries from the Stanford labs to design the therapy for Phase 1 trials,” Roncarolo said. “Instead of using drugs generated from biotech companies, we’re using drugs generated from our own labs.”

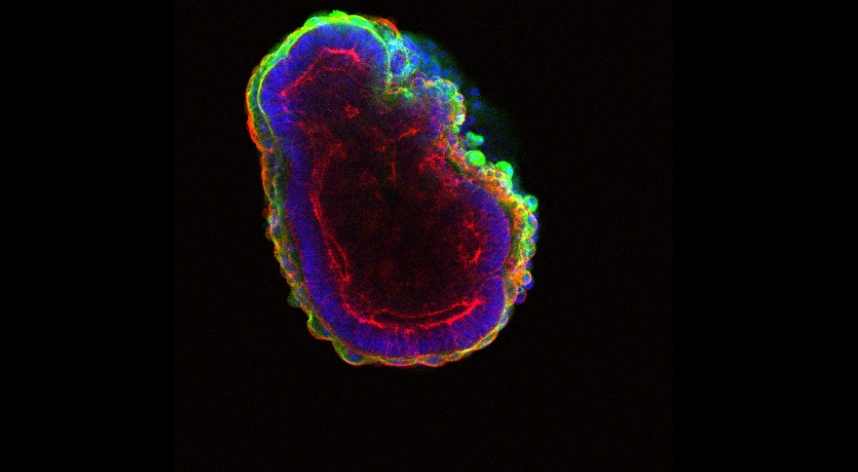

Certain complex diseases like type 1 diabetes, leukemia, lymphoma, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases and some pediatric cancers currently have no cure — but symptoms can be remedied using stem cell or gene therapy. Stem cell therapy takes stem cells from donors while gene therapy takes stem cells from the patient which were engineered to correct the genetic defect.

Diseases that aren’t genetic such as degenerative diseases, heart attacks and strokes can also be treated by stem cell transplantation. The CDCM will be equipped with the standard stem cell transplantation beds and investigative beds for clinical trials.

Roncarolo will lead a team of four other associate directors and physicians. Roncarolo said the team has specialties in multiple fields which will help address a range of genetic diseases.

“The aspirational goal of this center is to work in multidisciplinary teams with different expertise to cure patients with incurable diseases,” Roncarolo said.

According to one of these team members, Anthony Oro, MD, who is the Eugene and Gloria Bauer Professor and professor of dermatology, babies born with birth defects can have their defective genes taken out and corrected in a laboratory then re-inserted back using stem cells. Oro explained this is similar to a heart transplant, where a healthy organ replaces the damaged one to cure the patient. By using the person’s own DNA to manufacture the healthy genes and organs, the patient doesn’t need to be on immunosuppressant drugs or be matched with a donor who is compatible in blood type and tissue type.

“It’s a revolutionary idea to use cells and tissues as drugs to actually cure diseases which we haven’t been able to cure before because we only had surgery and medicine before,” Oro said. “The difference between potential cures and actual cures with huge effects is a mile apart. We’re bringing the potential of cures to reality here.”

Contact Jessica Zhang at jessica ‘at’ stanforddaily.com