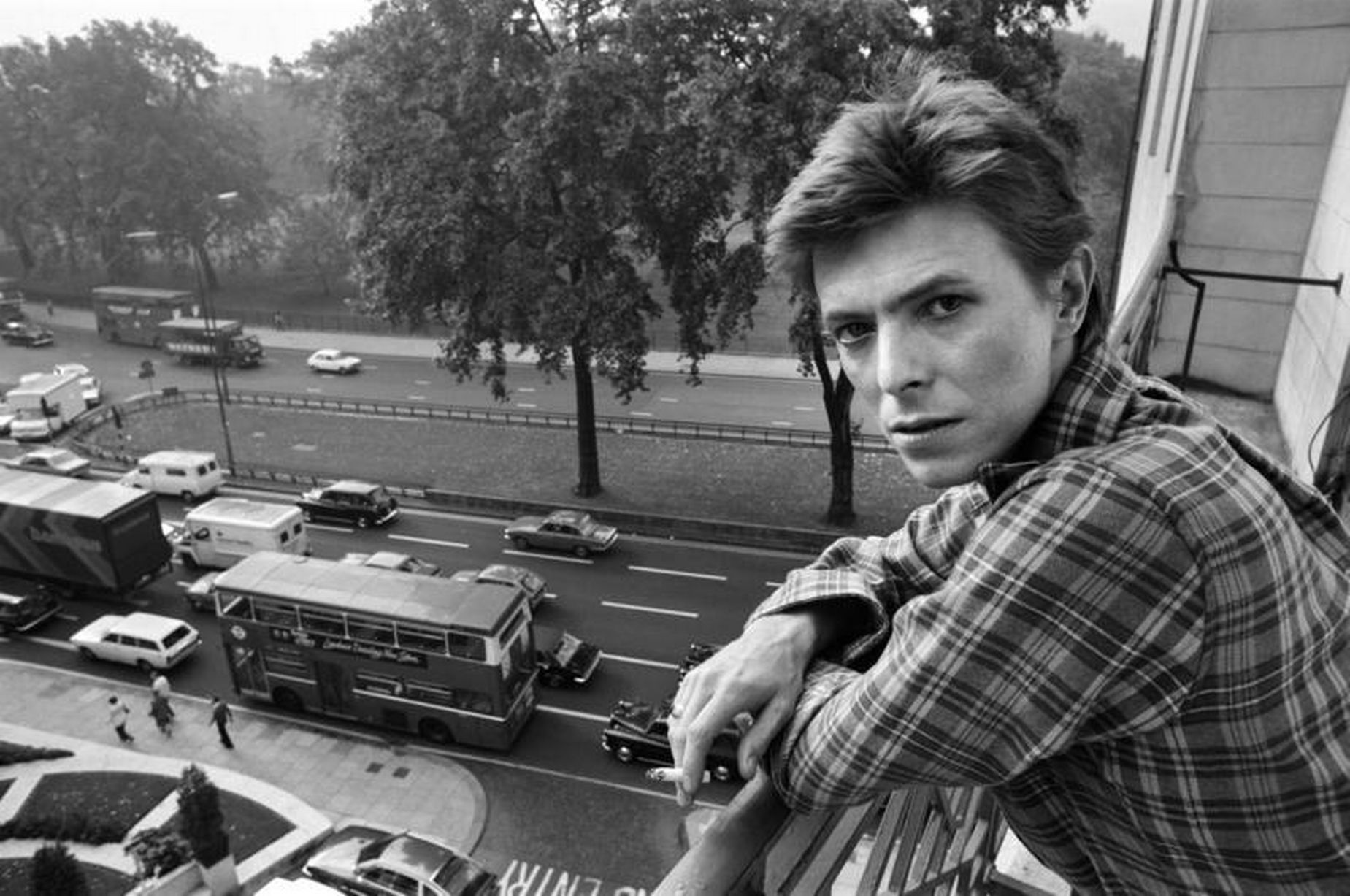

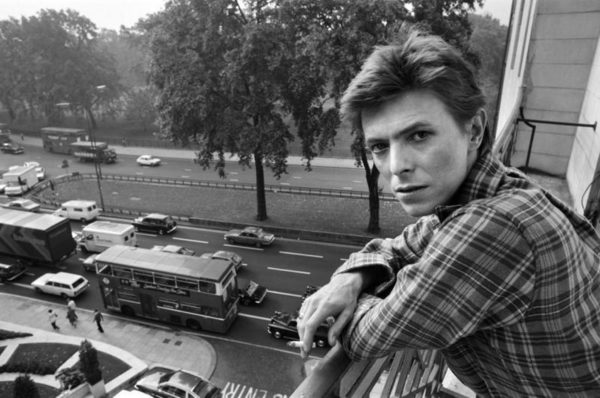

“Il miglior fabbro” is a phrase – meaning “the superior craftsman” – that Dante used to describe an Occitan troubadour of great fame and TS. Eliot later repurposed to describe his friend and poetic mentor, Ezra Pound. Now, over a year after his death and on the 40th anniversary of the landmark year in his career, it’s a good time to think of David Bowie – that protean, feline troubadour of the late 20th century, and there’s no better way to remember him than as the “miglior fabbro” – the consummate performer.

In 1977, Bowie had just moved to a Berlin of split personalities, a Berlin riven by the wall, half of it flowering and half in decay – a city and a state of mind that would be immortalized in film 10 years later in Wim Wender’s stirring tale of angels fallen to earth called “Wings of Desire” (1987). Something about Berlin at that time, a city possessed of vast but uncertain significance in world politics and history, seemed to lend itself to the mythical, the avant-garde – the broken but brilliant.

This must have appealed to Bowie, who had descended into various depths during the making of his previous album, 1976’s “Station to Station.” Living in Los Angeles – a city as unhealthy for the soul as it is for the lungs – he had been, according to legend, subsisting on a diet of milk, red peppers and cocaine. Plenty of evidence can be found for his drug habit and morbid fascination with occultism and kabbalah. Later in 1976, he was engulfed in scandal after appearing to perform a Nazi salute in public and making various vague statements professing pseudo-fascist sentiment.

Retreating to Berlin between 1977 and 1979, Bowie made three famous albums generally regarded by music critics as being of a piece: the Berlin Trilogy of “Low,” “Heroes” and “Lodger.” Depending on how much they favor experimentation and artistic exploration versus pop appeal, critics describe the trilogy as either Bowie’s “most artistic” phase or simply as his best. For Pitchfork, the track “A New Career in a New Town,” a track off 1977’s “Low,” seems to sum up the meaning Berlin held for Bowie at the time: a unified period of convalescence from the excess of Los Angeles, during which art replaced drugs and allowed Bowie to make his best work.

It’s a fair enough assessment. The Berlin Trilogy saw Bowie set aside the cold-hearted soul of “Young Americans” and “Station to Station” for more avant-garde, instrumental influences from krautrock bands like Kraftwerk and Neu!. Bowie, chameleon-like as always, also sought personal freedom from a sort of mental imprisonment in a persona and genre that had become riddled with a kind of malevolent irony.

But as others have pointed out, lumping the Berlin Trilogy together overlooks the continuity between “Station to Station” and “Low,” and also the pronounced differences between the three albums of the trilogy. “Heroes” and “Lodger” lack the punchy, hollow drumbeats of “Low” and have none of its sense of bashful (if alienated) naïveté. Already on “Heroes,” Bowie looks to Middle Eastern influence on “The Secret Life of Arabia,” something “Lodger” explores more deeply. “Heroes” is certainly grander than “Low” or “Lodger,” engaging more directly with passion and politics – most notably on the soaring, chugging title track about lovers separated by the Berlin Wall. The idea of a neat “Berlin Trilogy” is compelling, but it’s more fruitful to simply consider all of Bowie’s work in the mid- to late ’70s, regardless of city.

Bowie may have had much greater commercial success with his early ’70s glam work (e.g. “Ziggy Stardust”) and ’80s capitulation to dance-rock influences (e.g. “Let’s Dance”), and certain music writers seem to agree with the populace in exalting his two peaks in commercial success over the moodier Berlin period. But discerning listeners will know that Bowie’s late ’70s period is analogous to Dylan’s mid-’60s period in its relentless dynamism, personal instability and conflict between artistic value and pop appeal. In these albums – from the cold soul of “Young Americans” and “Station to Station” to the krautrock experimentalism of the Berlin Trilogy – Bowie was at the height of his talents: not necessarily as a pop-hook manufacturer or high-artistic sophisticate, but as a craftsman, a “fabbro.” These are the songs that continue to resonate and gain new qualities on further listening rather than feel cheap or repetitive, like the more simplistic hits like “Rebel Rebel” or “Under Pressure.”

Perhaps this is because they come from a less certain place in Bowie’s own life. He was indeed living as a troubadour, moving from place to place, lodging in one city and parting for another, as is reflected in his song titles: “Across the Universe,” the vain plea for a partner to “Stay,” a sense of traveling at the “Speed of Life” or, most obviously, the ambivalence of “Move On.”

On “Word on a Wing,” the most heartfelt song among the alienation of “Station to Station,” Bowie croons, “In this age of grand illusion/You walked into my life/Out of my dreams.” Either a love song or a prayer, it’s a song that takes up residence in the listener’s heart precisely because it’s uncertain, especially against the backdrop of irony against which so much of Bowie’s work leans. Religious experience or love, these things can happen even amidst irony, even on a diet of milk, red peppers and cocaine – though I don’t personally recommend it. The best we can do is often just what Bowie’s song professes to be, a word on a wing, uttered briefly before we’re swept along once more.

As for us, whether we’re seniors soon headed outward or freshmen spending uncertain first days on campus, what could be a better soundtrack than a period of Bowie’s work marked by a mastery of the art of transition? Especially in this: our age of grand illusion.

Contact Nick Burns at njburns ‘at’ stanford.edu.