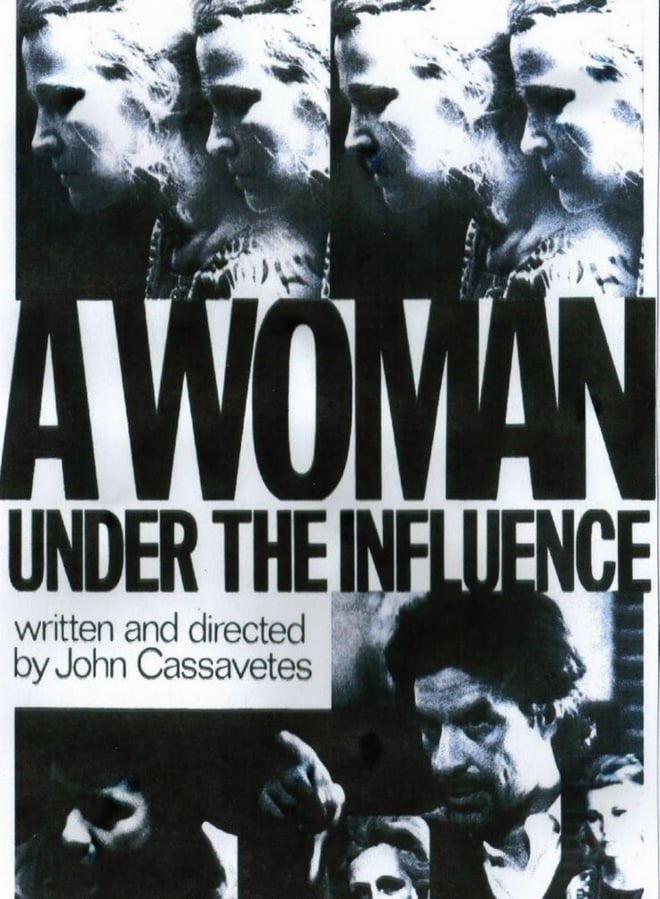

I see Richard Diebenkorn’s “Ocean Park #94” (1976), or I watch John Cassavetes’s “A Woman Under the Influence” (1974), and I’m reminded of home.

Home for me is Los Angeles. On freezing days like the ones we’re now enduring at Stanford, I’m California dreamin’, yes, but not for warmer climes — for the exact same cold, but dispersed across the sprawl of LA. On such a winter’s day, the LA I long for is overcast — which, to me, is not dreary. The one egregiously false note in Damien Chazelle’s “La La Land” (which moved me terribly) was the endless sun; surely Chazelle could have added a shot or a scene of Mia and Seb pummeled by a rainy frenzy without disrupting his Demy-derived realist magic. When LA shines, the days blend into one history-cancelling whole. But when it rains, that one day will stand out more profoundly to the Angeleno’s conscience than all the bright and sunny days combined.

Diebenkorn understood LA sweater weather. He moved from Berkeley to Santa Monica in 1967, whereupon he took up a professorship at UCLA. He set up his studio in Ocean Park, a tiny neighborhood in Santa Monica, and began painting the series that brought him worldwide acclaim: broad, busy networks of clumsy lines and dully shimmering color-patches, caught between figuration and abstraction. At Stanford, you can see two works from the Ocean Park series: the baby-blue “#60” (1973) in the Anderson Collection and the heavy-gray “#94” at the Cantor. Both are made from the perspective of someone who has understood LA climes to such a degree that the city’s haphazard urban sprawl is depicted in all its surprising beauty.

The two Diebenkorns are in the same family, but are strikingly different in mood and mode of approach. They both share the crisscrossing lines which shiver in the margins and go in wild directions, like LA’s improvisatory grid system. “#60” evokes LA life from one of the cool beaches near Santa Monica on an afternoon in late spring or early summer. From far away, the baby-blue sky is neatly divided from the cerulean sea; but as you walk closer and closer, they both seem to collapse into one another. It is the weird space between abstraction and figuration (a precious Diebenkorn zone) that allows Diebenkorn to depict the LA beachfront with resounding emotional accuracy.

“#94,” by contrast, is a bit tougher and wearier and less sure of its place in the world; all of the blue splendor has been segregated to a corner of the canvas, with insignificant blues speckled randomly in the main area of business: a gray-white swath. Mistakes are more on display in “#94”; Diebenkorn sets the pathways for lines in his mind, but his brushwork escapes his best efforts to contain the lines. They come out looking sloppy and dumb. In the middle of “#94”, it looks as if Diebenkorn drew a blue line, then changed his mind and tried to erase it with Wite Out—which only makes the suppression effort even more obvious. “#94” is not afraid of ugliness; in fact, it welcomes ugliness into its world. Ultimately, the emotions on display in the gloomy-brooding-hopeful “#94” are more diverse, more dispersive, than the Beach Boys optimism of “#60.”

These two Diebenkorns share a lot in sensibility with two contemporary films of the ’70s moment: Robert Altman’s offbeat take on the film noir “The Long Goodbye” (1973) and John Cassavetes’s “A Woman Under the Influence.” Just as “#60” and “#94” are in the same Diebenkorn family, the Altman and the Cassavetes were made are often grouped together as classics of 70s American independent cinema — but actually, they exist at opposite poles to each other. Altman has a much more rambling and jovial sense of humor. His visions of society are bleak, but his view of select communities are insular, warm, familial. In “The Long Goodbye,” Altman’s ’70s reimagining of Raymond Chandler’s hard-boiled Philip Marlowe, the joke is that Marlowe (Elliot Gould) is less concerned with solving the mystery of his friend’s wife’s murder than he is with finding his missing cat (and his favorite brand of cat food). The film is set largely at a beach-house in Malibu, about fifteen miles north of where Diebenkorn painted “#60.” The sky is always clear and bright, which conceals the ridiculous conspiracy over which it hangs like a cheerful Monty Python undertaker. “Long Goodbye” is becalmed and lackadaisical; its actors form a wonderful community that is carried through in the best Altmans (“Nashville,” “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” “California Split”).

In contrast to the mellow Altman, “A Woman Under the Influence” is one of the most stressful films imaginable. (Stock up on stamina, dear reader, before you tackle this 155-minute behemoth.) The camerawork is just as fluid as in “Long Goodbye,” but emotionally it is more tightly clenched and controlled, which gives its bursts of emotion an explosiveness that Altman’s films rarely have. Altman springs surprises on you where they are least expected; Cassavetes builds and builds to his operatic climaxes.

All four works represent Los Angeles with subtlety, intelligence and lack of pretense; they are cinematic exemplars of the city. They share one thing in common: None of them are “about” Los Angeles in any conventional sense. When one thinks of the biggest Los Angeles films, one recites a good yet stock list of usual suspects like kindergarten roll-call: “Double Indemnity,” “Chinatown,” “Blade Runner,” “L.A. Confidential,” “Mulholland Drive.” These are works which foreground Los Angeles, but only to milk its most common and basic dichotomy: the orange-juice veneer with a sinister-twisted-sick underbelly.

By contrast, “A Woman Under the Influence” takes place largely indoors, in one house, mainly in the living room. Location — the familiar architecture, buildings and monuments that distinguish a city —is never pushed. No character in “A Woman” ever states the name of the city they’re in.

Yet this is not Cassavetes’s cheap aim at a generalized universality. “A Woman,” and indeed most of Cassavetes’s features (“Faces,” “Minnie and Moskowicz,” “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie,” “Opening Night” “Love Streams” — all stealth L.A. classics) — are concerned with how people interact with the stark environments around them. Out-of-shape actresses looking for a final comeback. Divorced parents. Jazz players. Museum curators. Businessmen and prostitutes. Women on the verge of a nervous breakdown. It’s these people whom Cassavetes made the consistent subject of the lightning bolts he made outside of the American studio system between 1959 and 1984. By being so focused on developing an organic, spontaneous, jittering rhythm in his actors’ performance, Cassavetes also picked up on how a city like Los Angeles — with its wide expansive vistas, hence its lonely bigness — plays a central role in the trials and tribulations of a working-class suburban family like the Longhettis: the housewife Mabel (Gena Rowlands, John’s wife and closest artistic collaborator), the construction-worker father Nick (Peter Falk), and their three children.

L.A. is central to “A Woman” by being so seemingly marginal. It’s not just there because Cassavetes lived in Los Angeles for most of his adult life. The city shapes the characters’ relationships to the outside world: Why is Mabel so eccentric? Why is Nick so high strung? Why can’t he express to her, in clear terms, his love for her? The clogging stasis of their L.A. house provides some answers. The rotted aimlessness of domestic life is conveyed, silently, by Mabel’s late-night stroll along Hollywood Boulevard. How did she get there? Cassavetes elides this information, visualizing the process of Mabel in the throes of forgetting. The city is being erased from her view, yet is more present by its very erasure.

Where is she walking? We can tell it’s Hollywood Blvd., because Mabel walks — barefoot! — along the Hollywood Walk of Fame. A fine but less sensitive film director would have inserted an establishing shot, telling (not showing) the audience where they are located. Cassavetes communicates a great truth: how the city dweller internalizes the streets and directions and sights of their home city, which seem like a maze or (worse) boring to the uncaring outsider. (Contrast that to the heartless, condescending tourist’s view of L.A. taken by Woody Allen in “Annie Hall” [1977].) Because Cassavetes wants to us to understand Mabel’s head-space, he refuses to establish where we are; she knows, and we pick up, too.

I see a lot of the shiveringly imprecise fire of Diebenkorn in Cassavetes. Their images give off an amateurish, almost dumb quality. In “#94,” Diebenkorn draws two sides of a bottomless triangle. Then, he “ruins” the right side of the triangle by clogging it up with extra brush strokes of black. He only does this on the right side, thus giving the painting’s central shape (which isn’t even finished!) a lopsided effect. Yet, it is an effect which asks us to consider the touching beauty in clumsiness. Likewise, during Cassavetes’ time, film critics like Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris tore into him for his choppy, violent cuts from scene to scene. His editing does not follow neat, classical patterns of start-flow-pause-flow-stop; it lurches, screeches to a grinding halt, tracks back, skips ahead in time, remembers something that was important like seven minutes ago. To Cassavetes, this is the only accurate and honest way to present the world. The longest-lasting films always seek out truthful images; they must not be strictly factual or attempt to paint a slavish realism (indeed, when they are, the image is flat and dreary), but, at their best, they must reconstitute the merely mundane to a higher aesthetic, emotional, moral plane. They show universality through specificity, a sense of a world briefly experienced from the side-streams of our pathways through life. Both Cassavetes in film and Diebenkorn in painting worked in this terrain of shivering, wondrous marginality.

I return to Los Angeles. I fly back from Stanford to Los Angeles, see the plots of houses from my plane, and flash back to the Diebenkorn — which, when you stand far back (after a half-hour of looking at close-up details), looks as beautiful as seeing L.A. from the heavens. Then I remember the scene in “A Woman Under the Influence” which most excites me (and scares me): Mabel’s return, where Mabel (after spending six months in a mental asylum) has come back home and is greeted, with nervously fake smiles, by the very same people who committed her in the first place. I am excited and scared because I recognize it as the last quiet moment before the harrowing, stormy Act 3 — when all hell will break loose.

Mabel’s return is set against that typically overcast backdrop, that hot second where L.A. is overcome by grayness and drizzle. Cassavetes called this scene “a lucky accident.” On the morning of the day he was slated to film Mabel’s return, he was hoping and praying that it would rain; the script called for it. Yet all morning, the sky was stuck in a state of sunny “La La Land” perfection. Cass didn’t need perfection.

Suddenly, however, for a window that lasted for no longer than a half hour, the clouds rolled in. Rain softly fell. Cassavetes had his stage set by God: an ominous prelude of the final, hectic, stressful 30 minutes of “A Woman Under the Influence” where we see how love manifests itself with incoherence and ambiguity. Perfect L.A. weather is gone, now we are in shivering chaos, a zone between forms and non-forms. Humanity faced with its own mortality, idiocy, and disorientation. In L.A. that day, Cass got rain.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.