From green-lighting building projects to managing an over $20 billion endowment, the 33 members of Stanford’s Board of Trustees wield no small role in the University and its future.

The Board of Trustees was established on Nov. 11, 1885 by Leland and Jane Stanford to serve as directors for the University. The official job of a trustee, as expressed on the Board’s website, is to share “responsibility for setting the direction of the university, ensuring Stanford’s continued well-being and working to sustain its foundation of excellence.” In practice, this means duties such as consulting with top administrators, appointing presidents, approving budgets and making sometimes controversial final calls on matters like divestment from private prison affiliates and fossil fuels.

The Daily took a look at how the Board operates and how it shapes Stanford.

Who’s on the Board?

The trustees consist of the president of the University and 32 other members.

Candidates for trustee are not necessarily alumni of Stanford. According to University spokesperson E.J. Miranda, eight seats on the Board are designated for alumni nominated through the Alumni Committee on Trustee Nominations (ACTN). The Board’s trusteeship Committee reviews those picks in addition to making its own nominations. Selections then go before the entire Board.

Candidates who would be 70 or older when their term commences and current faculty, staff or students are not eligible. They must show a “serious commitment” to the University’s well-being.

The selection of new trustees occurs every two and a half years, with new trustees starting this April; the next selection process will begin in July of 2019. The Board is capped at 38 trustees who serve in five year terms.

Philip Taubman, the Board’s secretary, said one of his goals throughout his Board term and now as secretary is to increase Board diversity. He hopes to see greater representation of gender, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status and professions.

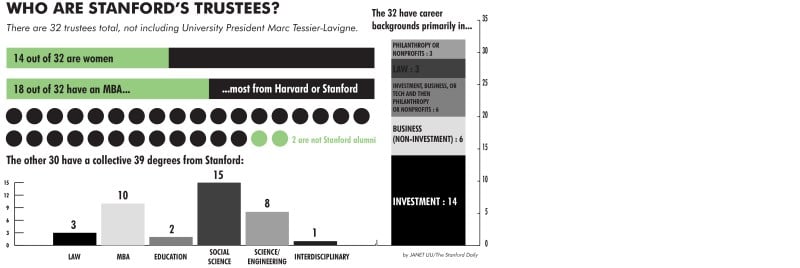

Taubman says representation of all but the latter has improved since the time he served on the Board from 1978 to 1982. Of the 32 trustees listed on the Board’s website in addition to University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, 14 have backgrounds primarily in investment, while another six hold business leadership roles outside the realm of investment. Another six started their careers in investment, business or tech before shifting to a focus on philanthropy or nonprofit work. Eighteen out of 32 have an MBA, mostly from Stanford or Harvard, and many head companies. Net worths in the millions and billions abound.

The newest members of the Board include Carrie Penner M.A. ’97, Walmart heir and Board chair at the Walton Family Foundation; Felix Baker ’91, Ph.D. ’98, a managing partner at Baker Borthers Investments; Jerry Yang ’90, M.S. ’90, who co-founded Yahoo! and AME Cloud Ventures; and Henry Fernandez M.B.A. ’83, CEO of MSCI Inc., which provides tools to support investment.

Meanwhile, Board members marking the end of their five year terms in March include Fred Alvarez ’72, J.D. ’75, partner at Jones Day; Gail Block Harris ’74, J.D. ’77, lead director of Evercore Partners; Bernard Liautaud M.S. ’85, general partner at Balderton Capital in London; and Lloyd Metz ’90, managing director of ICV Partners.

How does the Board operate?

The trustees meet five times every academic year, although additional sessions may be called; four of those times are on campus, and one is an offsite retreat with an emphasis on longer-term planning. In-person attendance is expected at every meeting.

The Board supports University leadership on a broad range of University issues — some of which are confidential, such as the selection process for an incoming University president. Secretary of the Board Taubman said the process must be confidential to protect individual rights of candidates; such secrecy is common among high-profile University searches.

Just as the president is selected by the Board, the Board can fire the president.

Board members also make decisions related to resource allocation, land use, academic programs, facility plans, University rules, federal and public support of education, community relations, minority representation, finance and fundraising. Trustees are volunteers and are responsible for all University decisions carried out in their name.

“The Board is a consulted body to support the president and provost with the perspective from the outside looking in,” Taubman said, adding that the Board exists for feedback and discussion.

“It’s a continuum of conversation in which the president and provost are in conversation with the Board about what’s happening at the University,” he said.

As Secretary of the Board, Taubman works closely with Tessier-Lavigne and Board Chair Jeff Raikes ’80 to discuss issues that the Board should address, ensure the Board plays the role it is designed to play, support management and plan meetings.

Once something takes the form of an action item, the Board needs to take a vote. According to Taubman, it is generally hard to predict whether a matter that comes up for discussion will make it to a vote.

As part of their advisory role, the trustees are assigned to various committees, which work on individual areas the Board presides over. Committees — which include Alumni and External Affairs, Development, Land and Buildings and Finance and Globalization — help the Board accomplish more specific projects; for example, the Land and Buildings Committee has focused on planning Stanford’s expansion into Redwood City.

Trustees serve on Board committees with students and faculty representatives. Additionally, trustees may be asked to serve on school or departmental committees or panels.

Board meetings last about a day and a half and comprise both committee and full group meetings. Meetings include presentations from various deans, department heads, on-campus institutes and other stakeholders aimed at providing a holistic perspective on current happenings on campus.

Individual consultation also occurs, especially with the Board chair, Taubman said.

The Board also reviews the annual budget developed by the provost, including on the construction of new buildings. Construction requires a number of approvals — site selection, design, concepts and financials — that the Board must vote on.

Outside of meetings, trustees might be asked to represent Stanford at events related to University matters and are encouraged to participate in alumni and fundraising activities.

Looking ahead

Recently, the Board has been reviewing the long-range planning process, an initiative launched by Tessier-Lavigne and Drell that called for community input on the University and its direction over the next 10 to 15 years. Ideas from the nearly 2,800 offered by students, faculty and staff — vetted and summarized into white papers by steering groups — go to University leadership for discussion supported by the Board.

“As trustees, we can leverage our networks, speak to the people to which we’re connected, learn their viewpoints and provide an external perspective that will contribute to the process,” Raikes said in an interview with Stanford News. “Stanford has big aspirations for its impact on the world. So a big question for us is: How can we as trustees tap into our external experience in ways that really enhance what [Tessier-Lavigne] and [Drell] and University leadership will do as part of long-range planning?”

Raikes said the Board’s 2018 spring retreat will focus on long-range planning as well as the negotiation of the Santa Clara County General Use Permit (GUP), which will govern the University’s land use for years to come and is negotiated between Stanford and the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors. Stanford is in the process of applying for a new GUP spanning 2018 to 2035 — as Taubman put it, the University is “running out of square footage.” The Board consults with Tessier-Lavigne on these negotiations.

According to Raikes, another important topic for trustees is Stanford Medicine, one of the biggest single contributors to the overall revenue of the University and home to revolutionary discoveries in healthcare and biotechnology.

“I expect that with the volatility with U.S. healthcare, there will be some twists and turns ahead,” Raikes told The Daily. “We don’t know what those things are going to be, but the Board can be very attentive to what those challenges and opportunities might be. We have Board members with specific expertise in the health care field, and they will be particularly valuable in those discussions.”

But Raikes also hopes trustees are able to learn more about discoveries made by all departments.

“Stanford has become a focal point in the world because of the University’s profile in a number of dimensions,” he told Stanford News.

Taubman hopes that Board matters and objectives become clearer to the public in cases when the work is not confidential.

“We’re trying to make an effort, and going forward, we are trying to make more of an effort to talk about more what the Board does,” Taubman explained, adding that the Board holds a press conference after every meeting to present the Board’s public agenda.

Raikes admitted that a challenge for trustees is staying in touch with campus life. He also noted the complexity of Stanford and its seven schools.

“I oftentimes hear from Board members it really takes a few years to get up to speed on the University,” he said. “Many are contributing right out of the gate, but they make a fair point.”

For students frustrated with the Board’s decision making on topics like divestment, the Board is disconnected from the student body.

In a response to trustees’ decision on fossil fuels in 2016, members of Fossil Free Stanford criticized the Board for “choosing cowardice over leadership.” Students stated that they were “deeply disappointed that Stanford’s Board has chosen to ignore the calls of the student body and Stanford community.”

Taubman views the Board differently.

“The Board is not some distant, detached, aloof institution,” he said. “I would hope students would think of the Board as a benevolent institution.”

Contact Gillian Brassil at gbrassil ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Josh Wagner contributed to this article.