As a metatheatrical work that also recognizes its metatheatricality, Qui Nguyen’s “Vietgone,” presented by the American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.), is one of those unique works that is able to avoid the cheesiness and embrace its campiness while still delivering a beautiful story. Through “Vietgone,” I realized that a piece of theater will never truly be fully comedic or fully dramatic — there’s ultimately no such thing. A piece of drama, like life, will have its moments of each, and that is really what makes a story function.

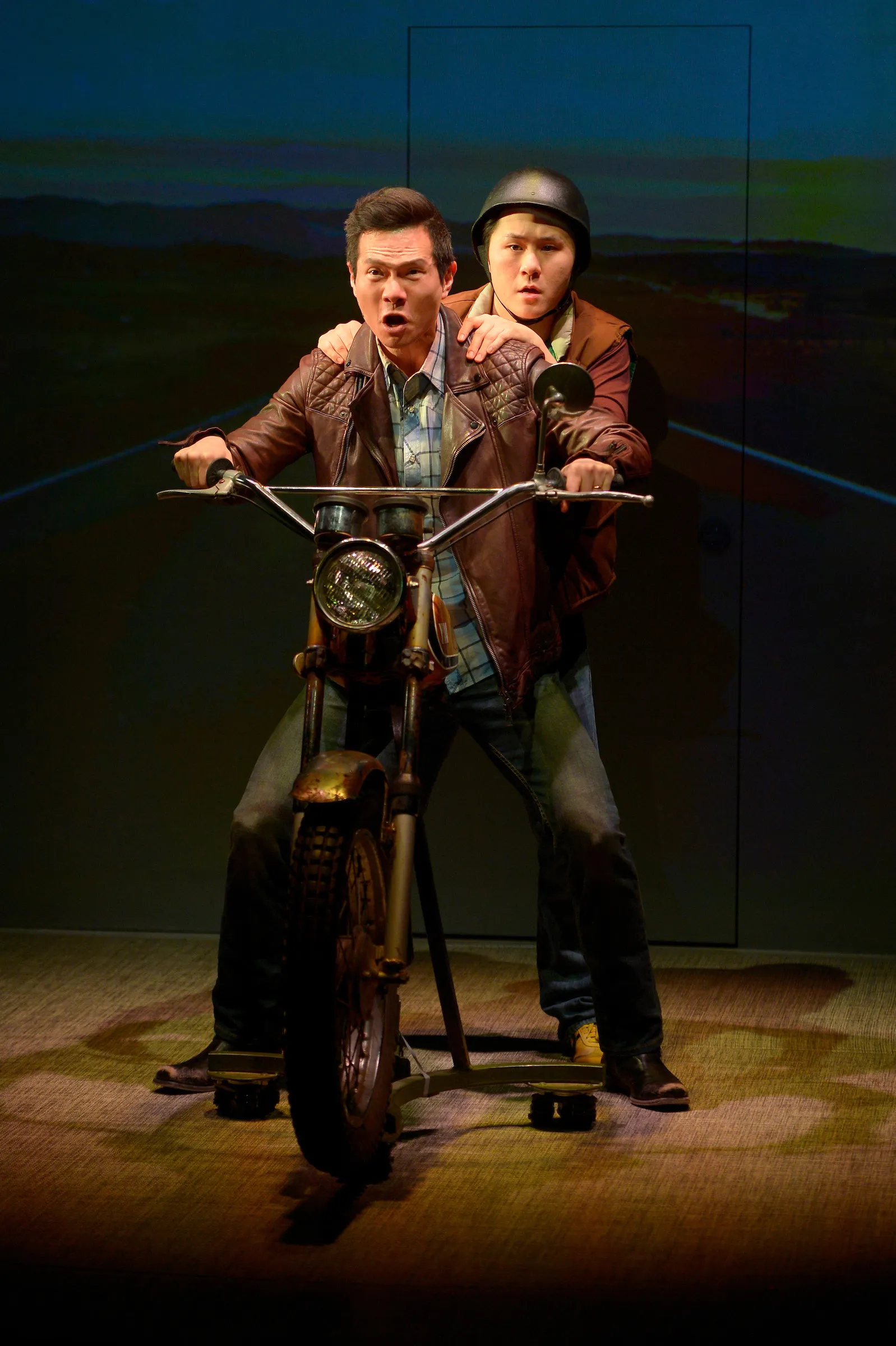

“Vietgone” flips masterfully back and forth between two timelines that converge. It’s the Vietnam War, and Quang (James Seol), a South Vietnamese pilot — who escaped before the Vietcong arrived and left his family back in his homeland — and his friend Nhan (Stephen Hu) are roadtripping to California in an attempt to make it back to South Vietnam to rescue Quang’s family from the horrors of the war. In another timeline four months earlier, the cynical Tong (Jenelle Chu) meets Quang at an American camp for Vietnamese refugees in Arkansas. Tong embraces her new home, while Quang and Tong’s mother Huong (Cindy Im) long to return back to Vietnam even as the Vietnam War rages on. I’ve honestly never laughed as hard as I have (in a long time, at least) at a short montage in the second act when Tong and Quang dance their way through a series of hyper-romanticized actions as Huong tries to separate them before accepting their love for each other.

Chu shines in “Vietgone,” from acting to a rare moment of powerful singing, balanced with Seol’s levelheaded but passionate Quang. The chemistry and dynamic between Chu and Im is undeniable, from Im’s Huong playing an overdramatic parent to Tong’s relatable cynicism towards feeling — well, feeling anything at all. While all the actors play many characters, each one is so distinct, showcasing the actors’ abilities to switch in and out between them. All of the actors are of Asian descent, and many of them also play white characters — but that doesn’t become an issue because of Nguyen’s clever use of language. Vietnamese characters speak like millennials would today, while White American characters speaking English express themselves in short phrases such as “Racism! Hamburger! Fries!” for both comedic effect and sociopolitical commentary. This is in contrast to Mia Chung’s use of language in “You for Me for You,” where the characters that speak English speak solely gibberish and then become more and more intelligible as the Korean characters learn English.

Similarly, “Vietgone” also uses another very unique form of language — many of the characters break into rap, like a musical, but other characters are usually not aware of this occurring. The rap functions as a sort of subconscious monologue for each of the characters as well. Nguyen’s grasp of rap is relatively strong, but clearly not as strong as it could be in comparison to, say, “Hamilton” (in comparison with Lin-Manuel’s strong hip-hop background). Nevertheless, it still works with the play, especially with the strong grasp of spoken language that appeals to younger modern audiences.

While “Vietgone” centers around the two main storylines, the play is also masterfully bookended by Nguyen’s own story. Nguyen himself (although in reality, played by Jomar Tagatac) “introduces” the play and its characters, warning the audience that this play is definitely not about his parents. Without spoiling it all, Nguyen (the writer, not the character), ties it all back together and brings it back home in a culmination of all thoughts and feelings — the story of Tong and Quang is close to home, yet “Vietgone” provides a lens on the Vietnam War and the refugee experience that is never illustrated in American media.

“Vietgone” brands itself not as a political play, but as one that tells a story, namely, a story of love. Yet through the play, characters mention how sentiments towards the Vietnam War are so different on both sides — many Americans regret the county’s involvement, yet many South Vietnamese citizens believe that without American intervention, South Vietnam would have been even worse off. This point rises to a fever pitch in the conclusion of the play, with Seol’s emotional portrayal of an older Quang as tender, heartfelt and close to home.

“Vietgone” is the first play in a long time at which I’ve genuinely cried. It wasn’t even the sadness or the happiness (okay, maybe a little happiness) — it was that Nguyen’s crafting of Tong and Quang’s story drew me in so closely that concluding their story became so emotional and I felt personally attached to the fate of their characters. A play hasn’t done that to me in a long time. And no, “Vietgone” isn’t a perfect work — but what work is? That doesn’t matter though — what matters is the story and the impact. “Vietgone” tells its audience that it’s not a story of war or struggle, but rather, one of love — and a story of love it so carefully and beautifully tells.

“Vietgone” is playing at the Strand Theater in San Francisco through April 22, 2018.

Contact Olivia Popp at oliviapopp ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Note: a previous version of this article incorrectly listed the author of “You for Me for You” as Jiehae Park. The correct author is Mia Chung.